Posted

by Big Gav

in

global warming,

globalisation,

media,

psychology,

reality insurgents

Bruce Sterling points to this interesting screed on the impossibility of getting everyone to agree on a set of facts in the modern media / psychological landscape - Reality as failed state.

So maybe what we have today are not problems, but meta-problems.

It is very useful to confirm our understanding with others, to meet with fellow humans – preferably face-to-face – strength flows from this.

However, disquiet remains - no pre-catastrophic change of course seems in any way likely. What we might call ‘Fabian’ environmentalism has failed.

Occasionally a scientist will be so overcome with horror that he will make a radical public pronouncement – like the drunken uncle at a wedding, he may well be saying what everyone knows to be true, pulling the skeletons out of the family closet for all to see, but, well, it just doesn’t do to say that sort of thing out loud at a formal function.

This is all a little bit strange.

We understand the problems. We also, pretty much, understand the solutions. But their real-world application is a whole unpickable, integrated clusterfuck.

I believe part of the meta-problem is this: people no longer inhabit a single reality.

Collectively, there is no longer a single cultural arena of dialogue.

What many techno-scientists fail to understand - and thus find most frustrating - about dealing with climate change deniers is that the denier has no real interest in engaging at the scientist’s level of reality.

The point, for the climate denier, is not that the truth should be sought with open-minded sincerity – it is that he has declared the independence of his corner of reality from control by the overarching, techno-scientific consensus reality. He has withdrawn from the reality forced upon him and has retreated to a more comfortable, human-sized bubble.

In these terms, the denier’s retreat from consensus reality approximates the role of the cellular insurgents in Afghanistan vis-a-vis the American occupying force: this overarching behemoth I rebel against may well represent something larger, more free, more wealthy, more democratic, or more in touch with objective reality, but it has been imposed upon me (or I feel it has), so I am going to withdraw from it into illogic, emotion and superstition and from there I am going to declare war upon it.

So, from this point of view, we can meaningfully refer to deniers, birthers, Tea Partiers and so forth as “reality insurgents”, and thus usefully apply the principles of 4GW to their activities – notably, they are clearly operating on a faster OODA loop than the defenders of mainstream reality, and thus able to respond more quickly, with greater innovation, than the sclerotic bureaucracy of institutionalised reality. [Open source bazaars – media-effective denial memes spread virally through community far quicker than effective strategies of rebuttal do.]

(n.b. There is a problematic tendency with a certain type of intellect – the scientist, the technocrat – which assumes that, because it is prepared to organise and change on the basis of dry statistics and data, then, if only everyone else could be exposed to the same data, there would be instant consensus for change. In fact, of course, the majority of human beings do not work like this.

Indeed, there is a positive, indeed, cognitively vital, aspect to intuitive thinking, and the realm of myths, narratives, paradigms of meaning, purpose and significance underlies even the worldview of the technocrat-scientist. Without an ability to engage with and understand the deep psyche, the techno-scientist is doomed to repeat his statistics into the ether without meaningful effect.)

The deniers are operating from a different ontological platform – an emotional reading of reality where there are forces wishing to control them and restrict their personal power and agency, and there are the forces of freedom, which is the side they believe they are on.

They are wrong, of course, but it is important to demonstrate to them that they are wrong on the level they are operating from – not by citing more climate statistics at them, but by demonstrating that the forces they are serving are actually the most vicious extant representatives of the control they profess to hate.

And all this is but one example of the ways in which the traditional ideological blocs of the Cold War have fragmented into complex multipartite civil reality wars.

Reality, you might say, as failed state; its interior collapsing into permanent conflict under the convergent pressures of deviant globalisation, its coasts predated upon by new mutant forms of memetic pirates.

Posted

by Big Gav

in

consumption,

psychology

The New York Times has an article on the psychology of happiness, looking at the relative effects of income, consumption levels and the value of experiences versus material goods - But Will It Make You Happy?. More ammunition for the 4 day working week...

A two-bedroom apartment. Two cars. Enough wedding china to serve two dozen people.

Yet Tammy Strobel wasn’t happy. Working as a project manager with an investment management firm in Davis, Calif., and making about $40,000 a year, she was, as she put it, caught in the “work-spend treadmill.”

So one day she stepped off.

Inspired by books and blog entries about living simply, Ms. Strobel and her husband, Logan Smith, both 31, began donating some of their belongings to charity. As the months passed, out went stacks of sweaters, shoes, books, pots and pans, even the television after a trial separation during which it was relegated to a closet. Eventually, they got rid of their cars, too. Emboldened by a Web site that challenges consumers to live with just 100 personal items, Ms. Strobel winnowed down her wardrobe and toiletries to precisely that number.

Her mother called her crazy.

Today, three years after Ms. Strobel and Mr. Smith began downsizing, they live in Portland, Ore., in a spare, 400-square-foot studio with a nice-sized kitchen. Mr. Smith is completing a doctorate in physiology; Ms. Strobel happily works from home as a Web designer and freelance writer. She owns four plates, three pairs of shoes and two pots. With Mr. Smith in his final weeks of school, Ms. Strobel’s income of about $24,000 a year covers their bills. They are still car-free but have bikes. One other thing they no longer have: $30,000 of debt.

Ms. Strobel’s mother is impressed. Now the couple have money to travel and to contribute to the education funds of nieces and nephews. And because their debt is paid off, Ms. Strobel works fewer hours, giving her time to be outdoors, and to volunteer, which she does about four hours a week for a nonprofit outreach program called Living Yoga.

“The idea that you need to go bigger to be happy is false,” she says. “I really believe that the acquisition of material goods doesn’t bring about happiness.”

While Ms. Strobel and her husband overhauled their spending habits before the recession, legions of other consumers have since had to reconsider their own lifestyles, bringing a major shift in the nation’s consumption patterns.

“We’re moving from a conspicuous consumption — which is ‘buy without regard’ — to a calculated consumption,” says Marshal Cohen, an analyst at the NPD Group, the retailing research and consulting firm.

Amid weak job and housing markets, consumers are saving more and spending less than they have in decades, and industry professionals expect that trend to continue. Consumers saved 6.4 percent of their after-tax income in June, according to a new government report. Before the recession, the rate was 1 to 2 percent for many years. In June, consumer spending and personal incomes were essentially flat compared with May, suggesting that the American economy, as dependent as it is on shoppers opening their wallets and purses, isn’t likely to rebound anytime soon.

On the bright side, the practices that consumers have adopted in response to the economic crisis ultimately could — as a raft of new research suggests — make them happier. New studies of consumption and happiness show, for instance, that people are happier when they spend money on experiences instead of material objects, when they relish what they plan to buy long before they buy it, and when they stop trying to outdo the Joneses.

If consumers end up sticking with their newfound spending habits, some tactics that retailers and marketers began deploying during the recession could become lasting business strategies. Among those strategies are proffering merchandise that makes being at home more entertaining and trying to make consumers feel special by giving them access to exclusive events and more personal customer service.

While the current round of stinginess may simply be a response to the economic downturn, some analysts say consumers may also be permanently adjusting their spending based on what they’ve discovered about what truly makes them happy or fulfilled.

“This actually is a topic that hasn’t been researched very much until recently,” says Elizabeth W. Dunn, an associate professor in the psychology department at the University of British Columbia, who is at the forefront of research on consumption and happiness. “There’s massive literature on income and happiness. It’s amazing how little there is on how to spend your money.”

CONSPICUOUS consumption has been an object of fascination going back at least as far as 1899, when the economist Thorstein Veblen published “The Theory of the Leisure Class,” a book that analyzed, in part, how people spent their money in order to demonstrate their social status.

And it’s been a truism for eons that extra cash always makes life a little easier. Studies over the last few decades have shown that money, up to a certain point, makes people happier because it lets them meet basic needs. The latest round of research is, for lack of a better term, all about emotional efficiency: how to reap the most happiness for your dollar.

So just where does happiness reside for consumers? Scholars and researchers haven’t determined whether Armani will put a bigger smile on your face than Dolce & Gabbana. But they have found that our types of purchases, their size and frequency, and even the timing of the spending all affect long-term happiness.

One major finding is that spending money for an experience — concert tickets, French lessons, sushi-rolling classes, a hotel room in Monaco — produces longer-lasting satisfaction than spending money on plain old stuff.

“ ‘It’s better to go on a vacation than buy a new couch’ is basically the idea,” says Professor Dunn, summing up research by two fellow psychologists, Leaf Van Boven and Thomas Gilovich. Her own take on the subject is in a paper she wrote with colleagues at Harvard and the University of Virginia: “If Money Doesn’t Make You Happy Then You Probably Aren’t Spending It Right.” (The Journal of Consumer Psychology plans to publish it in a coming issue.)

Thomas DeLeire, an associate professor of public affairs, population, health and economics at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, recently published research examining nine major categories of consumption. He discovered that the only category to be positively related to happiness was leisure: vacations, entertainment, sports and equipment like golf clubs and fishing poles.

Posted

by Big Gav

in

psychology

PhysOrg has an article on some research which suggests "when faced with a choice that could yield either short-term satisfaction or longer-term benefits, people with complete information about the options generally go for the quick reward" - Armed with information, people make poor choices, study finds. The unfortunate implication of this is that if you want people to act in their best long term interests, you probably need to manipulate them. It does make sense though - I suspect people decide that the future may not turn out as expected (or they may not necessarily be around for that long) and thus going for short term rewards has a higher chance of making them feel good.

The findings, available online in the journal Judgment and Decision Making, could help better explain the decisions people make on everything from eating right and exercising to spending more on environmentally friendly products.

"You'd think that with more information about your options, a person would make a better decision. Our study suggests the opposite," says Associate Professor Bradley Love, who conducted the research with graduate student Ross Otto. "To fully appreciate a long-term option, you have to choose it repeatedly and begin to feel the benefits."

As part of the study, 78 subjects were repeatedly given two options through a computer program that allowed them to accumulate points. For each choice, one option offered the subject more points. But choosing the other option could lead to more points further along in the experiment.

A small cash bonus was tied to the subjects' performance, providing an incentive to rack up more points during the 250 trial questions.

However, subjects who were given full and accurate information about what they would have to give up in the short term to rack up points in the long term, chose the quick payoff more than twice as often as those who were given false information or no information about the rewards they would be giving up.

In a real-life scenario, a student who stayed home to study and then learned he had missed a fun party would be less likely to study next time in a similar situation — even if that option provides more long-term benefits.

"Basically, people have to stay away from thinking about the short-term pains and gains or they are sunk and, objectively, will end up worse off," says Love.

Posted

by Big Gav

in

exercise,

psychology

The SMH has an article on research explorin the link between exercise and the growth of new brain cells - Jog your memory: brain cell secrets explored.

THE health benefits of a regular run have long been known, but scientists have never understood the curious ability of exercise to boost brain power.

Now researchers think they have the answer. Neuroscientists at Cambridge University have shown that running stimulates the brain to grow fresh grey matter and it has a big effect on mental ability.

A few days of running led to the growth of hundreds of thousands of brain cells that improved the ability to recall memories without confusing them, a skill that is crucial for learning and other cognitive tasks, researchers said.

The new brain cells appeared in a region that is linked to the formation and recollection of memory. The work reveals why jogging and other aerobic exercise can improve memory and learning, and potentially slow down the deterioration of mental ability in old age.

The research builds on a body of work that suggests exercise plays a vital role in keeping the brain healthy by encouraging the growth of brain cells. Previous studies have shown ''neurogenesis'' is limited in people with depression, but that their symptoms can improve if they exercise regularly.

Scientists are unsure why exercise triggers the growth of grey matter, but it may be linked to increased blood flow or higher levels of hormones that are released while exercising. Exercise might also reduce stress, which inhibits new brain cells through a hormone called cortisol.

Posted

by Big Gav

in

psychology

The Australian may have the answer to why that good looking blonde you've been going out with gets so cranky - 'Warlike' blondes get what they want - study.

IT'S official - blondes do have more fun. According to a study by the University of California, that's because blondes are more confident and aggressive, even displaying "warlike" tendancies to get their own way in life.

The study of 156 US students showed that because blondes believe they are more attractive to men than redheads or brunettes, they "feel more entitled" to getting their own way.

"What we did not expect to find was how much more warlike they are than their peers on campus," study leader Aaron Sell told UK tabloid The Sun. "Many blondes exist in a kind of bubble where they have been treated better than other people for so long, they may not even realise they are treated like a princess."

His research indicated that the more "special" people felt, judged by physical strength for men and looks for women, the more likely they were to get angry as a strategy to reach social goals.

Posted

by Big Gav

in

exercise,

psychology

The NYT has a post on the effect of exercise on the brain - Phys Ed: Why Exercise Makes You Less Anxious.

Researchers at Princeton University recently made a remarkable discovery about the brains of rats that exercise. Some of their neurons respond differently to stress than the neurons of slothful rats. Scientists have known for some time that exercise stimulates the creation of new brain cells (neurons) but not how, precisely, these neurons might be functionally different from other brain cells.

Phys Ed

In the experiment, preliminary results of which were presented last month at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience in Chicago, scientists allowed one group of rats to run. Another set of rodents was not allowed to exercise. Then all of the rats swam in cold water, which they don’t like to do. Afterward, the scientists examined the animals’ brains. They found that the stress of the swimming activated neurons in all of the brains. (The researchers could tell which neurons were activated because the cells expressed specific genes in response to the stress.) But the youngest brain cells in the running rats, the cells that the scientists assumed were created by running, were less likely to express the genes. They generally remained quiet. The “cells born from running,” the researchers concluded, appeared to have been “specifically buffered from exposure to a stressful experience.” The rats had created, through running, a brain that seemed biochemically, molecularly, calm.

For years, both in popular imagination and in scientific circles, it has been a given that exercise enhances mood. But how exercise, a physiological activity, might directly affect mood and anxiety — psychological states — was unclear. Now, thanks in no small part to improved research techniques and a growing understanding of the biochemistry and the genetics of thought itself, scientists are beginning to tease out how exercise remodels the brain, making it more resistant to stress. In work undertaken at the University of Colorado, Boulder, for instance, scientists have examined the role of serotonin, a neurotransmitter often considered to be the “happy” brain chemical. That simplistic view of serotonin has been undermined by other researchers, and the University of Colorado work further dilutes the idea. In those experiments, rats taught to feel helpless and anxious, by being exposed to a laboratory stressor, showed increased serotonin activity in their brains. But rats that had run for several weeks before being stressed showed less serotonin activity and were less anxious and helpless despite the stress.

Posted

by Big Gav

in

peak oil,

psychology

TOD commenter memmel's bizarre occasional allusions to elephants seem to have gone viral and infected the editors, with Nate unleashing a herd of elephants in his latest campfire post - Enter the Elephant.

There are 2 thresholds occurring in resource depletion space. 1)the shifting but low odds on steering the societal Titanic ( turbo-capitalism) away from the iceberg (energy decline) and 2) what individuals are doing to increase their own odds of success of navigating the coming transition. Progress on one is probably uncorrelated to progress on the other.

Sometimes I think I am on the verge of really understanding not only the details of our global situation, but which paths are still open to humanity, and which are dead ends. Sure, I know there is a gargantuan amount of unknown knowledge out there (what we don't know we don't know), but it seems like if I could just get a little bit more info and synthesis, that I could convey such to others and the tumblers of the 'solution' lock combination could be made clear. A concise well written expose in the major newspapers etc. and people would start to change their behavior in the significant magnitude that will needed.

I have come to see this as delusional thinking. As I wrote about in 'Whither TheOildrum?', I suspect the analyst community (to which I belong), are largely puzzle solvers. The unexpected reward from finding new empirical connections and lateral thinking tricks our dopamine superhighway into thinking we are effecting change, when in reality the results are akin to an arcade game. We rationalize said situation by hoping/assuming that others will advance our analysis and effect the appropriate policy steps that logically follow. I have come to believe this is not reality. The reality is people look at these graphs and analyses a)because they are interesting in the same way watching a scary movie with buttered popcorn is interesting and b)they want to improve their own situation (by investing in oil future, or gold, etc.).

What makes paradigms change? There is a kind of recipe. First, things need to be bad in relation to how they were. Relative not absolute. (If our GDP and consumption got cut in half we would still be richer than kings and queens of a few generations ago, yet the psychological withdrawal for most of such a trajectory would be devastating.) Second there needs to be a quantification and general dissemination of knowledge and details of the problem. (enter ecological economists, Ron Paul, theoildrum.com, etc. ) Though these facts may not be assimilated by the mainstream, the fact that some people are snaking an empirical path to the heart of discontent is important. It is how this factual spine makes its way into the social zeitgeist which is the relevant question du jour. Third, there needs to be a real event that pulls at peoples emotions so much that they perceive that doing nothing is worse than doing something. Such a recipe, or close to it, exists today.

Posted

by Big Gav

in

psychology

Reuters has an article that should bring a wry smile to the average doomer's face - Thinking negatively can boost your memory, study finds.

Bad moods can actually be good for you, with an Australian study finding that being sad makes people less gullible, improves their ability to judge others and also boosts memory.

The study, authored by psychology professor Joseph Forgas at the University of New South Wales, showed that people in a negative mood were more critical of, and paid more attention to, their surroundings than happier people, who were more likely to believe anything they were told.

"Whereas positive mood seems to promote creativity, flexibility, cooperation, and reliance on mental shortcuts, negative moods trigger more attentive, careful thinking paying greater attention to the external world," Forgas wrote.

"Our research suggests that sadness ... promotes information processing strategies best suited to dealing with more demanding situations."

Posted

by Big Gav

in

nature,

psychology

MSNBC has an article on the effect of exposure to the natural environment on people's attitudes - Looking at nature makes you nicer.

“If it weren’t for Central Park, all us New Yorkers would kill each other,” says Ruta Fox, a 50-something jewelry entrepreneur from Manhattan. “It’s the saving grace of this city.”

As extreme as that sounds, Fox may be on to something. In a set of recent experiments, researchers at the University of Rochester in New York monitored the effects of natural versus artificial environments — and found that nature actually makes us nicer.

“Previous studies have shown the health benefits of nature range from more rapid healing to stress reduction to improved mental performance and vitality,” says Richard Ryan, a professor of psychology, psychiatry and education at the University of Rochester and co-author of the study, published in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

“Now we’ve found nature brings out more social feelings, more value for community and close relationships. People are more caring when they’re around nature,” he says.

Posted

by Big Gav

in

politics,

psychology

Guy Rundle at Crikey has an interesting series on the death of the political left (I imagine someone could do a similar series on the death of the right as well now) and some ruminations on how things may develop in the coming years - The slow death of the unified left.

That left split with the birth of the ‘New Left’ in the 60s, which explicitly rejected that form and those priorities — and drew instead on its own life experience, largely that of student and bohemian life, to suggest a diffused and individualistic model of organisation, and an idea of imminently utopian change (‘sous les paves, la plage’ — ‘beneath the paving stones, the beach’ – meaning, in Paris 68, that in pulling them up and chucking them at people, you were also digging down to the natural, playful world).

From that movement sprang one that would prove more durable — the green left, emphasising for the first time that the Left should not be about more, but about less: less consumption, less waste, less destruction. In the ensuing decades, the political form the Green Left has taken is parliamentary and social democratic — its program is overwhelmingly one of restraint and regulation of economic processes, rather than of a change in their character.

More importantly, the rise of the green left also put two ‘lefts’ fundamentally in opposition to each other. The old Marxist/social democratic left had been interested in increasing society’s productive base, and running it in a different way. The new green left took the old ‘new left’ critique of industrial civilisation as alienated etc and twinned it with the growing evidence of biosphere destruction by business-as-usual. However the more parliamentary the movement has become, the more it has departed from suggesting an alternative basis to life, one radically buying out of the dominance of industrial civilisation, to one regulating it.

The ‘promethean’ left and the green left clashed as early as the 1970s, in Australia with the tussle over the Green Bans movement in Sydney. The leadership of the NSW Builders Labourers Federation — Mundey, Owens and Pringle – had sparked a mass social movement which not only saved much of heritage Sydney, but extended the idea of what unions should do (as Pat Fiske’s great doco ‘Rocking the Foundations’ shows, one of the final strikes was against a Sydney Uni college, to force it to change its policy of expelling homosexuals.) The NSW BLF’s point was that workers making a qualitative assessment of what they did and didnt build was a massive political shift, and movement forward.

The NSW BLF campaign was knocked on the head by Norm Gallagher and the federal leadership, Maoist-oriented, who were partly concerned (reasonably enough it might be said) that the increasingly wild worker-student-anarchist campaign would expose the union to an attack it could not win – but also that the business of Marxists was not to be preserving the old, but creating the new, and eventually taking control of it.

Today, a lot of those Maoists and Prometheans — Chris Pearson, Keith Windschuttle, Piers Akerman — have turned up on the right rather than the left, from whence they reserve their greatest fury for the Greens. But it is effectively a restaging of an earlier intra-left dispute. (you can also see this in the substantial anti-Green campaigns by the UK Spiked group, the successors to the small-but-influential Revolutionary Communist Party.

Thus we have the strange spectacle today of a Labor ‘left’ which is really a centre-right regulatory outfit, a ‘green left’ which is really a social democratic-left regulatory outfit, and a ‘cultural left’ which has no real interest in the economic base at all. The genuine Marxist left is a small, ossified remnant, whose capacity for discipline and focused work can still generate impressive change (despite the high profile cultural leftists, 90% of the grunt for the anti-mandatory detention movement was Trots, in the end) is useful, but whose broader message sounds like something from the 3rd century church fathers.

There is, in that respect, no ‘Left’.

So why is this man smiling?

The answer is firstly that the contradictions of the global system (yes, yes, The Holy Grail) are now so obvious, apparent, and in motion that not merely the prospect but the necessity of real cultural-political change in the future is now evident – though it is harder to see from Australia than just about everywhere else.

The second is that those who look for old-style parties and lock-step organisations for signs of political life are looking in all the wrong places. Without rethinking it, they have taken up the old metaphor of the road, and the journey as the image of left political struggle, seen that we’re not very far along it, and concluded that things are dire. But society has changed so that that metaphor no longer applies, and causes you to miss what is immanent (though not imminent) in global society.

Take the contradictions first. The global financial economy is based on a model that has barely lasted a decade without shuddering in a near-collapse. It involves the western economies turning themselves over to consumption, service sales and rents (on IP mainly) as their core activities, supplied by China, India etc, who are turning themselves into giant factories to supply them.

This arrangement has allowed the global economy to cook the books on the main problem that capitalist development always faces – that of overproduction (keep wages low, and you deprive yourself of consumers. Raise wages and you lower profits). China’s enormous supply of labour has made it possible to operate as one giant factory, with the consumers elsewhere (ie in the West). How do you keep this going? You lend the West the money to consume beyond any possible return of its own withered productive base.

Whatever patches have been put on patches since September last year, one thing is obvious - the West is broke. It has been broke for five years, if not longer. Australia is an exception, due to resources, Sweden due to retaining a high-end industrial base. But the big guys — the US, the UK, continental Europe — are in deep trouble.

But so too are the developing nations, for a declining ability to sell to the West means the necessity of developing their own consumers — at which case the roaring growth rates begin to slow. This is primarily a political problem for at that point, China gets ‘stuck’. Its current social contract between city and country is that city people will get very rich, and offer country people the chance to make better money than back-breaking subsistence farming, with the prospect of intergenerational betterment. Once that slows, the

Ditto in India, which hasn’t really begun to modernise. The short expression of all this is that global capitalist development is not a replay of western capitalist development — for the simple reason that western capitalist development depended on imperialism and third world underdevelopment to keep firing. The idea that these billion+ societies are going to turn into western countries, with 1% directly involved in agriculture, is fantastical. The levels of industrial overproduction would be so monumental that we would have to find people on Jupiter to sell shit to.

Long before most people realise that things simply cannot happen that way, the gears will have crunched. What will animate the world in this century will be conflict between country and city (and country-within-the-city, ie the global slums) in a way that makes the Chinese Revolution of 1949 disclose its true character as mere curtain-raiser. Once it becomes clear to the global country that the flow of wealth has diminished to sub-trickle.

Of course this conflict intersects with another contradiction — that of biosphere impact. Quite aside from climate change, it is obvious that levels of consumption, and the management of production, is so chaotic that radical change — involving a shift in the idea of property — will become necessary. Two matters in particular cannot not have an effect — the collapse of global fish stocks, and a resultant collapse in the food chain, and global demands on ground water due to commercial agriculture, and resultant regional eco-catastrophes. Both of these conditions threaten within a generation, both are beyond our current ability, and possibly any conceivable ability, to create a techno-fix. They will become motive forces in history, because they will intersect with the above raw deal between the city and the country. It is not western Greens who will be driving this, but hundreds of millions of peasants, whose only two choices are struggle or death.

The third contradiction is in the West, and it is the deforming effects that the political-economic system has on our culture. Uniquely in history, the contemporary west has made the cultural system subject to the economy, made it its market, raw material and dumping ground. For a century or more this process was held in check by conservative institutions, and, when these collapsed, attacked by the counterculture, which provided an alternative. When that collapsed, the commodity and the commodified image moved to the centre of social life. Since the commodity is essentially nihilistic – a commodity is simply something whose value is expressed in terms of every other value – its effect, initially liberating from inherited authority (the church, etc) is ultimately nihilistic too.

Socially, the effects of this are to create increasingly atomised societies, in which it is increasingly impossible to imagine solidarity or close connection beyond the immediate family - and then to offer as a substitute either a cynical and masochistic celebration of atomisation (ie most reality TV shows) or literal-minded religiosity, essentially channelled from the middle ages, ie from the last pre-capitalist period.

Psychologically, the effects are to create increasingly ungrounded people. If the society you grow up in is atomised, then an identity never ‘sets’. The liberation that offers is the freedom to determine your own identity. What it removes is the capacity for any identity to be meaningful.

The effect is that a vague depressive sense of nothingness becomes the psychological common cold of hypermodernity. It is then addressed as a disease, and treated with medications (anti-depressants) which stimulate the brain chemicals (such as serotonin) which used to be replenished by meaningful social life. Push this sort of culture for another generation, build a world where ever larger numbers of people live in this world of shadows, and eventually that deep-seated and often unvocalised sense of deep futility will become a historical force in its own right.

Really, I think most people, reflecting on the world as it is, have some intimation of the triple crisis as I’ve sketched it out above. What does not appeal is the idea that socialism is any sort of answer – associated as it is with state-heavy systems, either torpid or lethal or both. Nor does any sort of party or organised political activity suggest itself as even comprehensible to people who live within an atomised world.

What does make radical change possible, sudden and likely however is that processes of self-management are immanent, there beneath the surface, within hypermodernity, in a way they haven’t been previously, to a sufficient degree. That’s a result of better education, intellectual labour – but also about the fact that we all spend so much time thinking about how systems work.

Imagine for example, that the next global capitalist crisis – 2010, 2017?, December? - caused the holding corporation that owned our power utilities to collapse, in a way that was beyond the government to refloat with a bailout (because the government itself was now all bailed out out). Would we simply persist in darkness? Or would, after some disruption and confusion, the engineers and managers who had been running the thing anyway, simply continue to run it. Would they and others be able to use the networks already existing to keep power supply intersected with other areas of the economy, using a mixture of money and free exchange, but without the notion that this was simply being done to return dividends to shareholders? Would they appoint an interim board of control, preserve managerial and scientific hierarchies etc.

Would it then become clear, from practice, not from theory, that a power station is a social institution, not a private one, and that a whole set of arrangements that are neither private ownership nor state control can be made in running our lives?

Posted

by Big Gav

in

ask nature,

biophilia,

green buildings,

psychology

Word of the week is "biophilia", from this interview in Yale Environment 360 - Reconnecting with Nature Through Green Architecture.

Stephen R. Kellert, a social ecologist, has spent much of his career thinking and writing about biophilia, the innate human affinity for nature. His most recent book (with co-editors Judith H. Heerwagen and Martin L. Mador) is Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. It’s an exploration of how we cut ourselves off from nature in the way we design the buildings and neighborhoods where we live and work. And it’s an argument for re-connecting these spaces to the natural world, with plenty of windows, daylight, fresh air, plants and green spaces, natural materials, and decorative motifs from the natural world.

Kellert and his co-authors believe that people learn better, work more comfortably, and recuperate more successfully in buildings that echo the environment in which the human species evolved. The new volume brings together the evidence, which is strongest in health care. In one study, for instance, spinal surgery patients in rooms with bright sunlight needed 22 percent less pain medication than patients in darker recovery rooms. But firm evidence of improvements in workplace productivity, absenteeism, employee retention and other bottom-line criteria is still too patchy for most companies to make the commitment to rethinking design.

Kellert himself recently put his biophilic ideas to the test at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, where he’s the Tweedy/Ordway Professor of Social Ecology. As one of the driving thinkers in the design of the school’s new headquarters, opened early this year, he pushed successfully for use of wood surfaces from the school’s own forests, green courtyards, and many other biophilic features. Kellert has also served as an advisor to such prominent green building projects as Bank of America’s new office tower in midtown Manhattan, Goldman Sachs’ Jersey City campus, and the new Sidwell Friends Middle School campus in Washington, D.C.

After 30 years in academia, Kellert recently cut back on his teaching to join Environmental Capital Partners, a newly formed private equity firm, investing in companies offering green products and services. But, in an interview with Yale Environment 360, he admits that persuading his partners to invest in biophilic design is just a dream, for now.

Yale Environment 360:

So let’s start with the status quo, can you talk about one building that really epitomizes what we’re doing wrong, that cuts people off from nature instead of connecting them to it?

Steven Kellert:

One simple statistic is that the majority of people who work in office buildings in the United States work in a windowless environment. And look at the way we decorate or don’t decorate hospital rooms, for example. A good many of them are windowless, especially the older kinds. They’re barren. There’s not much attempt to incorporate any kind of organic — even simulated organic — characteristics. There’s a great recent study by Roger Ulrich. There are identical emergency room rooms. One is this windowless, barren environment, with nothing on the wall, and the barest, meanest of furnishings. And it’s a room that is characterized by hostility, anxiety, and even acting-out behavior. And then they transform the room — it’s the same room, still windowless, but they put décor in there that had natural materials, it had patterns on the couches that mimicked natural forms; they had pictures on the wall. I have a picture of the two side by side — and you only have to see it to recognize in yourself which place would you rather be, and the empirical data was dramatic. Less hostility, less aggression, less acting-out behavior, and this is not just amenity value, it’s actual performance and productivity.

The same thing occurs in the workplace. Why do people experience flagging morale and fatigue and higher absenteeism in these windowless environments? Why are they far far more likely to try to incorporate some kind of — usually fairly pathetic — but to incorporate some kind of expression of organic quality — they’ll have a Sierra Club calendar, they’ll have a potted plant, much more likely than say somebody working in a perimeter in a windowed environment. The problem is that that’s really superficial, there’s not really an experiential engagement, and so after a while even though you’ve got a beautiful Sierra Club calendar you barely see it anymore, it’s like your screensaver, which saves you for a little while and then it’s just background Muzak, or whatever. ...

Posted

by Big Gav

in

internet,

psychology

Salon has a review of a book (Rapt: Attention and the Focused Life") on the modern day epidemic of shortened concentration spans - Why can't we concentrate?. Click through and read the rest of the article, if you can be bothered...

Here's a fail-safe topic when making conversation with everyone from cab drivers to grad students to cousins in the construction trade: Mention the fact that you're finding it harder and harder to concentrate lately. The complaint appears to be universal, yet everyone blames it on some personal factor: having a baby, starting a new job, turning 50, having to use a Blackberry for work, getting on Facebook, and so on. Even more pervasive than Betty Friedan's famous "problem that has no name," this creeping distractibility and the technology that presumably causes it has inspired such cris de coeur as Nicholas Carr's much-discussed "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" essay for the Atlantic Monthly and diatribes like "The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future," a book published last year by Mark Bauerlein. ...

In essence, attention is the faculty by which the mind selects and then zeroes in on the most "salient" aspect of any situation. The problem is that the brain is not a unified whole, but a collection of "systems" that often come into conflict with each other. When that happens, the more primitive, stimulus-driven, unconscious systems (the "reactive" and "behavioral" components of our brains) will usually override the consciously controlled "reflective" mind.

There are excellent reasons for this. In the conditions under which humanity evolved, threats had the greatest salience; individuals who spotted and eluded dangers before they went chasing after rewards tended to live long enough to pass on their traits to future generations. As a result, we inherited from our distant ancestors the tendency to pay greater attention to the unpleasant and troublesome elements of our surroundings, even when those elements have evolved from real menaces, like a crocodile in the reeds, to largely insignificant ones like nasty anonymous postings in a Web discussion.

Likewise, our interest is grabbed by movement, bright colors, loud noises and novelty -- all qualities associated with potential meals or threats in a natural setting; we are hard-wired to like the shiny. The attention we bring to bear on less exciting objects and activities, where the payoff may be long-term rather than immediate, requires a conscious choice. This is the kind of attention that opens into complex, nuanced and creative thought, but it tends to get swamped by the more urgent demands of the reactive system unless we exert ourselves to overcome our instincts. The reflective system flourishes best when the environment is relatively free of bells and whistles screaming "Delicious fruit up here!" or "Large animal approaching over there!"

The conditions conducive to deep thought have become increasingly rare in our highly mediated lives. When the physical limitations on print and broadcast media kept the number of competitors for our attention relatively few, some candidates could afford to appeal to our reflective side. Now we live in an attention economy, where the most in-demand commodity is "eyeballs." As more options crowd the menu, direct appeals to the reactive mind in the form of bright colors or allusions to sex, aggression, tasty foods and so on, take over.

The machinations of late capitalism aren't the only things driving the incessant pinging on our reactive attention systems, either. If you're like most people, you will keep checking for new e-mail despite the unresolved messages that await in your inbox. The already-read messages may even deal with urgent matters like an impatient question from your boss or appealing subjects like possible vacation rentals, yet there's something lackluster about them compared to what might be wending its way to you over the Internet right this minute. Despite the fact that the incoming messages are probably not any more compelling than the ones you've already received, they're more attention-grabbing simply by virtue of being new. When Carr complains of the compulsion to skim and move on that possesses readers of online media, a major culprit is this instinct-driven craving for the novelties that lurk a mere mouse-click away.

Quantcast

The fact that sensationalism sells is hardly news, but less well-known is the fact that a constant diet of reactive-system stimuli has the potential to alter our very brains. The plasticity of the brain, scientists concur, is much greater than was once thought. New brain-imaging technologies have demonstrated that people consistently called upon to use one aspect of their mental toolbox -- the famously well-oriented London cabbies, for example -- show enhanced blood flow to and development of those parts of the brain devoted to, say, spatial cognition. In "The Overflowing Brain: Information Overload and the Limits of Working Memory," Torkel Klingberg, a Swedish professor of cognitive neuroscience, argues that careful management and training of our working memory (which deals with immediate tasks and the information pertaining to them) can increase its capacity -- that your data-crammed noggin can essentially build itself an annex.

But while it's one thing to accommodate more information, it's another to engage with it fundamentally, in a way that allows us to perceive underlying patterns and to take concepts apart so that we can put them back together in new and constructive ways. The early human who was constantly fending off leopards or plucking low-hanging mangoes never got around to figuring out how to build a house. Because leopards and mangoes were for the most part relatively few and far between, most of our ancestors found it easier to summon the kind of attention conducive to completing projects that, in the long term, make life measurably better. Ironically, while immediate threats and fleeting treats are comparatively much rarer in our complex social world, the attention system designed to deal with them has been kept on perpetual alert by both design and happenstance.

As long as we remain only dimly aware of the dueling attention systems within us, the reactive will continue to win out over the reflective. We'll focus on discussion-board trolls, dancing refinancing ads, Hollywood gossip and tweets rather than on that enlightening but lengthy article about the economy or the novel or film that has the potential to ravish our souls. Tracking the shiny is so much easier than digging for gold! Over time, our brains will adapt themselves to these activities and find it more and more difficult to switch gears. Gallagher's exhortations to scrutinize and redirect our attention could not be more timely, but actually accomplishing such a feat increasingly feels beyond our control. I can't speak personally to the effectiveness of meditation, Gallagher's recommended remedy for chronic distraction, but the effectiveness of meditative practices (religious or secular) in reshaping the brain have also been abundantly demonstrated.

Posted

by Big Gav

in

psychology

The New York Times has an interesting (and yes - completely off topic) article on the impact of having friends on your health - What Are Friends For? A Longer Life.

In the quest for better health, many people turn to doctors, self-help books or herbal supplements. But they overlook a powerful weapon that could help them fight illness and depression, speed recovery, slow aging and prolong life: their friends.

Researchers are only now starting to pay attention to the importance of friendship and social networks in overall health. A 10-year Australian study found that older people with a large circle of friends were 22 percent less likely to die during the study period than those with fewer friends. A large 2007 study showed an increase of nearly 60 percent in the risk for obesity among people whose friends gained weight. And last year, Harvard researchers reported that strong social ties could promote brain health as we age.

“In general, the role of friendship in our lives isn’t terribly well appreciated,” said Rebecca G. Adams, a professor of sociology at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. “There is just scads of stuff on families and marriage, but very little on friendship. It baffles me. Friendship has a bigger impact on our psychological well-being than family relationships.” ...

Bella DePaulo, a visiting psychology professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, whose work focuses on single people and friendships, notes that in many studies, friendship has an even greater effect on health than a spouse or family member. In the study of nurses with breast cancer, having a spouse wasn’t associated with survival.

While many friendship studies focus on the intense relationships of women, some research shows that men can benefit, too. In a six-year study of 736 middle-age Swedish men, attachment to a single person didn’t appear to affect the risk of heart attack and fatal coronary heart disease, but having friendships did. Only smoking was as important a risk factor as lack of social support.

Exactly why friendship has such a big effect isn’t entirely clear. While friends can run errands and pick up medicine for a sick person, the benefits go well beyond physical assistance; indeed, proximity does not seem to be a factor.

It may be that people with strong social ties also have better access to health services and care. Beyond that, however, friendship clearly has a profound psychological effect. People with strong friendships are less likely than others to get colds, perhaps because they have lower stress levels.

Last year, researchers studied 34 students at the University of Virginia, taking them to the base of a steep hill and fitting them with a weighted backpack. They were then asked to estimate the steepness of the hill. Some participants stood next to friends during the exercise, while others were alone.

The students who stood with friends gave lower estimates of the steepness of the hill. And the longer the friends had known each other, the less steep the hill appeared.

“People with stronger friendship networks feel like there is someone they can turn to,” said Karen A. Roberto, director of the center for gerontology at Virginia Tech. “Friendship is an undervalued resource. The consistent message of these studies is that friends make your life better.”

Posted

by Big Gav

in

global warming,

psychology

The NYT has a (long) article on the psychological basis for the low level of importance placed on global warming and other environmental issues by Americans - Why Isn’t the Brain Green?.

Two days after Barack Obama was sworn in as president of the United States, the Pew Research Center released a poll ranking the issues that Americans said were the most important priorities for this year. At the top of the list were several concerns — jobs and the economy — related to the current recession. Farther down, well after terrorism, deficit reduction and energy (and even something the pollsters characterized as “moral decline”) was climate change. It was priority No. 20. That was last place.

A little more than a week after the poll was published, I took a seat in a wood-paneled room at Columbia University, where a few dozen academics had assembled for a two-day conference on the environment. In many respects, the Pew rankings were a suitable backdrop for the get-together, a meeting of researchers affiliated with something called CRED, or the Center for Research on Environmental Decisions. A branch of behavioral research situated at the intersection of psychology and economics, decision science focuses on the mental processes that shape our choices, behaviors and attitudes. The field’s origins grew mostly out of the work, beginning in the 1970s, of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, two psychologists whose experiments have demonstrated that people can behave unexpectedly when confronted with simple choices. We have many automatic biases — we’re more averse to losses than we are interested in gains, for instance — and we make repeated errors in judgment based on our tendency to use shorthand rules to solve problems. We can also be extremely susceptible to how questions are posed. Would you undergo surgery if it had a 20 percent mortality rate? What if it had an 80 percent survival rate? It’s the same procedure, of course, but in various experiments, responses from patients can differ markedly.

Over the past few decades a great deal of research has addressed how we make decisions in financial settings or when confronted with choices having to do with health care and consumer products. A few years ago, a Columbia psychology professor named David H. Krantz teamed up with Elke Weber — who holds a chair at Columbia’s business school as well as an appointment in the school’s psychology department — to assemble an interdisciplinary group of economists, psychologists and anthropologists from around the world who would examine decision-making related to environmental issues. Aided by a $6 million grant from the National Science Foundation, CRED has the primary objective of studying how perceptions of risk and uncertainty shape our responses to climate change and other weather phenomena like hurricanes and droughts. The goal, in other words, isn’t so much to explore theories about how people relate to nature, which has been a longtime pursuit of some environmental psychologists and even academics like the Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson. Rather, it is to finance laboratory and field experiments in North America, South America, Europe and Africa and then place the findings within an environmental context.

It isn’t immediately obvious why such studies are necessary or even valuable. Indeed, in the United States scientific community, where nearly all dollars for climate investigation are directed toward physical or biological projects, the notion that vital environmental solutions will be attained through social-science research — instead of improved climate models or innovative technologies — is an aggressively insurgent view. You might ask the decision scientists, as I eventually did, if they aren’t overcomplicating matters. Doesn’t a low-carbon world really just mean phasing out coal and other fossil fuels in favor of clean-energy technologies, domestic regulations and international treaties? None of them disagreed. Some smiled patiently. But all of them wondered if I had underestimated the countless group and individual decisions that must precede any widespread support for such technologies or policies. “Let’s start with the fact that climate change is anthropogenic,” Weber told me one morning in her Columbia office. “More or less, people have agreed on that. That means it’s caused by human behavior. That’s not to say that engineering solutions aren’t important. But if it’s caused by human behavior, then the solution probably also lies in changing human behavior.”

Among other things, CRED’s researchers consider global warming a singular opportunity to study how we react to long-term trade-offs, in the form of sacrifices we might make now in exchange for uncertain climate benefits far off in the future. And the research also has the potential to improve environmental messages, policies and technologies so that they are more in tune with the quirky workings of our minds. As I settled in that first morning at the Columbia conference, Weber was giving a primer on how people tend to reach decisions. Cognitive psychologists now broadly accept that we have different systems for processing risks. One system works analytically, often involving a careful consideration of costs and benefits. The other experiences risk as a feeling: a primitive and urgent reaction to danger, usually based on a personal experience, that can prove invaluable when (for example) we wake at night to the smell of smoke.

There are some unfortunate implications here. In analytical mode, we are not always adept at long-term thinking; experiments have shown a frequent dislike for delayed benefits, so we undervalue promised future outcomes. (Given a choice, we usually take $10 now as opposed to, say, $20 two years from now.) Environmentally speaking, this means we are far less likely to make lifestyle changes in order to ensure a safer future climate. Letting emotions determine how we assess risk presents its own problems. Almost certainly, we underestimate the danger of rising sea levels or epic droughts or other events that we’ve never experienced and seem far away in time and place. Worse, Weber’s research seems to help establish that we have a “finite pool of worry,” which means we’re unable to maintain our fear of climate change when a different problem — a plunging stock market, a personal emergency — comes along. We simply move one fear into the worry bin and one fear out. And even if we could remain persistently concerned about a warmer world? Weber described what she calls a “single-action bias.” Prompted by a distressing emotional signal, we buy a more efficient furnace or insulate our attic or vote for a green candidate — a single action that effectively diminishes global warming as a motivating factor. And that leaves us where we started.

Debates over why climate change isn’t higher on Americans’ list of priorities tend to center on the same culprits: the doubt-sowing remarks of climate-change skeptics, the poor communications skills of good scientists, the political system’s inability to address long-term challenges without a thunderous precipitating event, the tendency of science journalism to focus more on what is unknown (will oceans rise by two feet or by five?) than what is known and is durably frightening (the oceans are rising). By the time Weber was midway into her presentation, though, it occurred to me that some of these factors might not matter as much as I had thought. I began to wonder if we are just built to fail. ...

Posted

by Big Gav

in

cities,

mental health,

psychology

The Boston Globe has an interesting article on how cities impact mental function - How the city hurts your brain (via Idleworm).

THE CITY HAS always been an engine of intellectual life, from the 18th-century coffeehouses of London, where citizens gathered to discuss chemistry and radical politics, to the Left Bank bars of modern Paris, where Pablo Picasso held forth on modern art. Without the metropolis, we might not have had the great art of Shakespeare or James Joyce; even Einstein was inspired by commuter trains.

(Yuko Shimizu for the Boston Globe)

And yet, city life isn't easy. The same London cafes that stimulated Ben Franklin also helped spread cholera; Picasso eventually bought an estate in quiet Provence. While the modern city might be a haven for playwrights, poets, and physicists, it's also a deeply unnatural and overwhelming place.

Now scientists have begun to examine how the city affects the brain, and the results are chastening. Just being in an urban environment, they have found, impairs our basic mental processes. After spending a few minutes on a crowded city street, the brain is less able to hold things in memory, and suffers from reduced self-control. While it's long been recognized that city life is exhausting -- that's why Picasso left Paris -- this new research suggests that cities actually dull our thinking, sometimes dramatically so.

"The mind is a limited machine,"says Marc Berman, a psychologist at the University of Michigan and lead author of a new study that measured the cognitive deficits caused by a short urban walk. "And we're beginning to understand the different ways that a city can exceed those limitations."

One of the main forces at work is a stark lack of nature, which is surprisingly beneficial for the brain. Studies have demonstrated, for instance, that hospital patients recover more quickly when they can see trees from their windows, and that women living in public housing are better able to focus when their apartment overlooks a grassy courtyard. Even these fleeting glimpses of nature improve brain performance, it seems, because they provide a mental break from the urban roil.

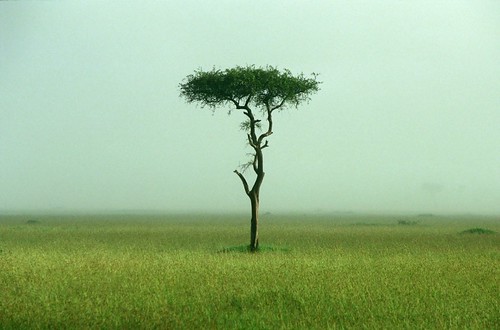

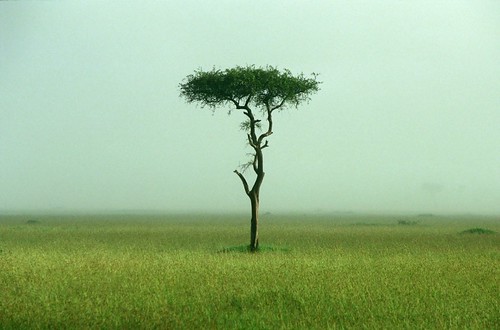

This research arrives just as humans cross an important milestone: For the first time in history, the majority of people reside in cities. For a species that evolved to live in small, primate tribes on the African savannah, such a migration marks a dramatic shift. Instead of inhabiting wide-open spaces, we're crowded into concrete jungles, surrounded by taxis, traffic, and millions of strangers. In recent years, it's become clear that such unnatural surroundings have important implications for our mental and physical health, and can powerfully alter how we think.

This research is also leading some scientists to dabble in urban design, as they look for ways to make the metropolis less damaging to the brain. The good news is that even slight alterations, such as planting more trees in the inner city or creating urban parks with a greater variety of plants, can significantly reduce the negative side effects of city life. The mind needs nature, and even a little bit can be a big help.

Consider everything your brain has to keep track of as you walk down a busy thoroughfare like Newbury Street. There are the crowded sidewalks full of distracted pedestrians who have to be avoided; the hazardous crosswalks that require the brain to monitor the flow of traffic. (The brain is a wary machine, always looking out for potential threats.) There's the confusing urban grid, which forces people to think continually about where they're going and how to get there.

The reason such seemingly trivial mental tasks leave us depleted is that they exploit one of the crucial weak spots of the brain. A city is so overstuffed with stimuli that we need to constantly redirect our attention so that we aren't distracted by irrelevant things, like a flashing neon sign or the cellphone conversation of a nearby passenger on the bus. This sort of controlled perception -- we are telling the mind what to pay attention to -- takes energy and effort. The mind is like a powerful supercomputer, but the act of paying attention consumes much of its processing power.

Natural settings, in contrast, don't require the same amount of cognitive effort. This idea is known as attention restoration theory, or ART, and it was first developed by Stephen Kaplan, a psychologist at the University of Michigan. While it's long been known that human attention is a scarce resource -- focusing in the morning makes it harder to focus in the afternoon -- Kaplan hypothesized that immersion in nature might have a restorative effect.

Imagine a walk around Walden Pond, in Concord. The woods surrounding the pond are filled with pitch pine and hickory trees. Chickadees and red-tailed hawks nest in the branches; squirrels and rabbits skirmish in the berry bushes. Natural settings are full of objects that automatically capture our attention, yet without triggering a negative emotional response -- unlike, say, a backfiring car. The mental machinery that directs attention can relax deeply, replenishing itself.

"It's not an accident that Central Park is in the middle of Manhattan," says Berman. "They needed to put a park there."

In a study published last month, Berman outfitted undergraduates at the University of Michigan with GPS receivers. Some of the students took a stroll in an arboretum, while others walked around the busy streets of downtown Ann Arbor.

The subjects were then run through a battery of psychological tests. People who had walked through the city were in a worse mood and scored significantly lower on a test of attention and working memory, which involved repeating a series of numbers backwards. In fact, just glancing at a photograph of urban scenes led to measurable impairments, at least when compared with pictures of nature.

"We see the picture of the busy street, and we automatically imagine what it's like to be there," says Berman. "And that's when your ability to pay attention starts to suffer."

This also helps explain why, according to several studies, children with attention-deficit disorder have fewer symptoms in natural settings. When surrounded by trees and animals, they are less likely to have behavioral problems and are better able to focus on a particular task.

Studies have found that even a relatively paltry patch of nature can confer benefits. In the late 1990s, Frances Kuo, director of the Landscape and Human Health Laboratory at the University of Illinois, began interviewing female residents in the Robert Taylor Homes, a massive housing project on the South Side of Chicago.

Kuo and her colleagues compared women randomly assigned to various apartments. Some had a view of nothing but concrete sprawl, the blacktop of parking lots and basketball courts. Others looked out on grassy courtyards filled with trees and flowerbeds. Kuo then measured the two groups on a variety of tasks, from basic tests of attention to surveys that looked at how the women were handling major life challenges. She found that living in an apartment with a view of greenery led to significant improvements in every category.

"We've constructed a world that's always drawing down from the same mental account," Kuo says. "And then we're surprised when [after spending time in the city] we can't focus at home."

But the density of city life doesn't just make it harder to focus: It also interferes with our self-control. In that stroll down Newbury, the brain is also assaulted with temptations -- caramel lattes, iPods, discounted cashmere sweaters, and high-heeled shoes. Resisting these temptations requires us to flex the prefrontal cortex, a nub of brain just behind the eyes. Unfortunately, this is the same brain area that's responsible for directed attention, which means that it's already been depleted from walking around the city. As a result, it's less able to exert self-control, which means we're more likely to splurge on the latte and those shoes we don't really need. While the human brain possesses incredible computational powers, it's surprisingly easy to short-circuit: all it takes is a hectic city street.