The Fat Man, The Population Bomb And The Green Revolution

Posted by Big Gav in agriculture, futurism, herman kahn, limits to growth, minerals, phosphorus, population

Paul Krugman had a fun article in the New York Times last week - Gore Derangement Syndrome - looking at the neoconservative meltdown over Al Gore's Nobel Peace Prize win (apparently the last time this happened was when Martin Luther King won the award back in 1964).

On the day after Al Gore shared the Nobel Peace Prize, The Wall Street Journal’s editors couldn’t even bring themselves to mention Mr. Gore’s name. Instead, they devoted their editorial to a long list of people they thought deserved the prize more.

While Krugman concentrates on the frothing far right, they aren't the only ones having conniptions - Alexander Cockburn at Counterpunch (which is nominally far left, though it does wander erratically about the political compass at times in search of suitable vantage points to achieve their mission of throwing mud at everyone) also emitted an angry anti-Gore outburst, accusing the rise of concern about global warming of being nothing but a stunt put on for the benefit of the nuclear industry.

The UN often has an inside track on the "Peace" prize. The UN Peace-Keeping Forces got it in 1988. In 1986 another enthusiast for attacking Iraq and Iran, Elie Wiesel, carried off the trophy. Aside from Kissinger, probably the biggest killer of all to have got the peace prize was Norman Borlaug, whose "green revolution" wheat strains led to the death of peasants by the million. ...

The specific reason why this man of blood shares the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with the IPCC is for their joint agitprop on the supposed threat of anthropogenic global warming. Bogus science topped off with toxic alarmism. It's as ridiculous as as if Goebbels got the Nobel Peace Prize in 1938, sharing it with the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for his work in publicizing the threat to race purity posed by Jews, Slavs and gypsies. ...

Of course Al Gore has been a shil for nuclear power ever since he came of age as a political harlot for the Oakridge nuclear laboratory in his home state of Tennessee. The practical beneficiary of the baseless hysteria over "anthropogenic global warming" is the nuclear power industry. This very fall, as Peter Montague describes at length in our current CounterPunch newsletter, this industry is reaping the fruits of Al Gore's campaigning. Congress has finally knocked aside the regulatory licensing processes that have somewhat protected the public across recent decades. The starting gun has sounded, and just about the moment Gore and his co-conspirators at the IPCC collect their prizes, the bulldozers will be breaking ground for the new nuclear plants soon to spring like Amanita phalloides--just as deadly--across the American landscape.

While the whole piece is wildly contrarian, one piece of character assassination thrown in by Cockburn is the accusation that "green revolution" pioneer Norman Borlaug (who also won the Nobel Peace Prize) was responsible for "wheat strains that led to the death of peasants by the million". While I have no comprehension of what he is going on about here (as I understand it, the green revolution led to a massive fall in starvation and malnutrition and was responsible for a surge in global population levels, rather than enormous mounds of dead peasants), it does provide a nice lead in to one of those meandering rants I like to embark on from time to time (which once again will give Bart an opportunity to call me long-winded and in dire need of an editor - or as one redditor once put it "this is a colossal assemblage of other people's reviews and redundant analysis").

So - no news tonight, just an exploration of some more of the history around The Limits To Growth and related memes.

Now, the "fat man" referred to in the title isn't Al Gore (whose weight seems to be an issue amongst some parts of the blogosphere though he doesn't look all that large to me), but instead one of the more unusual icons of the cold war era (and one of those wisdom deficient products of the RAND Corporation I referred to in "The Shockwave Rider") - strategist and futurist Herman Kahn.

In the post "Silent Spring" era, environmental issues made their way to the forefront of popular thinking for a while, prompting books like "The Limits To Growth", which I've gone on about at length previously, and more alarmist works like Paul Ehrlich's "The Population Bomb". Herman Kahn was a conservative who set up, along with a group of other RANDians, an organisation called the Hudson Institute, which Wikipedia refers to as "the organization about which the phrase 'think tank' was originally coined".

The Hudson Institute seems to have drifted ever further to the right over the years, which is an achievement of sorts given its starting position (though to be fair, Kahn himself seemed a fairly moderate conservative in some ways). One of their original bugbears was the Club Of Rome and the environmental movement in general, and it has been a bastion of global warming denial in more recent times. If the SourceWatch profile is correct, they also seem to have a strong interest in promoting industrialised agriculture and opposing organic farming (their stance on apple pie and being nice to puppies is unknown but they may well oppose these too).

If you go to the Wikipedia link and the SourceWatch profile you'll find lists of the scary crew of characters, such as Richard "the prince of darkness" Perle, associated with the organisation today (with the honourable exception of William Odom, who has been strong on opposing the Iraq war and the expansion of the surveillance state).

The New Yorker has an interesting article on Herman Kahn himself, which should give you an idea of what he was all about and some of his stranger beliefs, which resulted in him being one of the inspirations for the "Dr Strangelove" character in Stanley Kubrick's movie.

Herman Kahn was the heavyweight of the Megadeath Intellectuals, the men who, in the early years of the Cold War, made it their business to think about the unthinkable, and to design the game plan for nuclear war—how to prevent it, or, if it could not be prevented, how to win it, or, if it could not be won, how to survive it. The collective combat experience of these men was close to nil; their diplomatic experience was smaller. Their training was in physics, engineering, political science, mathematics, and logic, and they worked with the latest in assessment technologies: operational research, computer science, systems analysis, and game theory. The type of war they contemplated was, of course, never waged, but whether this was because of their work or in spite of it has always been a matter of dispute. Exhibit A in the case against them is a book by Kahn, published in 1960, “On Thermonuclear War.”

Kahn was a creature of the RAND Corporation, and RAND was a creature of the Air Force. In 1945, when the United States dropped atomic bombs nicknamed Little Boy and Fat Man on Japan, the Air Force was still a branch of the Army. The bomb changed that. An independent Department of the Air Force was created in 1947; the nation’s nuclear arsenal was put under its command; and the Air Force displaced the Army as the prima donna of national defense. Whatever it wanted, it mostly got. One of the things it wanted was a research arm, and rand was the result. (rand stands for Research ANd Development.) RAND was a line item in the Air Force budget; its offices were on a beach in Santa Monica. Kahn joined in 1947.

In his day, Kahn was the subject of many magazine stories, and most of them found it important to mention his girth—he was built, one journalist recorded, “like a prize-winning pear”—and his volubility. He was a marathon spielmeister, whose preferred format was the twelve-hour lecture, split into three parts over two days, with no text but with plenty of charts and slides. He was a jocular, gregarious giant who chattered on about fallout shelters, megaton bombs, and the incineration of millions. Observers were charmed or repelled, sometimes charmed and repelled. Reporters referred to him as “a roly-poly, second-strike Santa Claus” and “a thermonuclear Zero Mostel.” He is supposed to have had the highest I.Q. on record.

Sharon Ghamari-Tabrizi’s “The Worlds of Herman Kahn” (Harvard; $26.95) is an attempt to look at Kahn as a cultural phenomenon. (Kahn is the subject of a full-length biography with a similar title, “Supergenius: The Mega-Worlds of Herman Kahn,” by a former colleague, Barry Bruce-Briggs, which, though partisan, is thorough and informed, and which Ghamari-Tabrizi, strangely, never mentions.) She is not the first to treat Kahn as more an artist than a scientist. In 1968, when Kahn was at the height of his celebrity, Richard Kostelanetz wrote a profile of him for the Times Magazine in which he suggested that Kahn had “a thoroughly avant-garde sensibility.” He meant that Kahn was uninhibited by conventional ways of thinking, alert to abandon positions that were starting to seem obsolete, continually trying to find new ways to see around the next corner.

As Ghamari-Tabrizi points out, this was the mode of RAND itself. The atmosphere there was one part Southern California nonconformity and two parts University of Chicago rigor. People at rand imagined themselves to be well out on the curve. They read widely and held salons, where they talked futurology; some had arty décor in their offices and took up gourmet cooking. They were eggheads in a world of meatheads, and they regarded the uniformed military man in the same way that the baseball statistician Bill James regards Don Zimmer: as a relic of the pre-scientific dark ages, when the wisdom of experience passed for strategic thought. The wisdom of experience was useless in the atomic era, because no one had ever participated in a nuclear exchange. ...

The defense policy of the Eisenhower Administration, announced by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in an address to the Council on Foreign Relations in 1954, was the doctrine of “massive retaliation.” Dulles explained that the United States could not afford to be prepared to meet Soviet aggression piecemeal—to have soldiers ready to fight in every place threatened by Communist expansion. The Soviets had a bigger army, and they threatened in too many places. The solution was to make it clear that the American response to Soviet aggression anywhere would be a nuclear attack, at a time and place of America’s choosing. It was a first-strike policy: if provoked, the United States would be the first to use the bomb. An overwhelming nuclear arsenal therefore acted as a deterrent on Soviet aggression. Eisenhower called the policy the New Look.

The New Look was good for the Air Force, because it made the nuclear arsenal, and its delivery system of bombers and, later on, missiles, the country’s principal strategic resource. But the analysts at rand considered massive retaliation a pathetically crude idea, an atomic-age version of Roosevelt’s big stick. They thought that it was practically an invitation to the Soviets to precede any local aggression by a preëmptive first strike on American bomber bases, eliminating the nuclear threat on the ground and forcing the United States into the land war it was unprepared to fight. There was also a major credibility problem. How aggressive did the Soviets need to be to trigger a thermonuclear response? Was the United States willing to kill millions of Russians, and to put millions of Americans at risk of dying in a counterattack, in order to prevent, say, South Korea from going Communist? Or West Berlin? There had to be some options available between disapproval and annihilation. The doctrine of massive retaliation was a deterrent—a way to prevent war—but it was inherently destabilizing. National defense policy required something more nuanced, and figuring out what, since Eisenhower was uninterested, fell to the people at rand.

Kahn began working on the problem not long after Dulles’s speech. In 1959, he spent a semester at the Center for International Studies, at Princeton, and then toured the country delivering lectures on deterrence theory. In 1960, Princeton University Press published a version of the lectures (with much added material) as “On Thermonuclear War.” Kahn was not really a writer, and his book—six hundred and fifty-one pages—is shaggy, overstuffed, almost free-associational, with a colorful use of capitalization and italics, long excurses on the strategic lessons of the First and Second World Wars, and the sorts of proto-PowerPoint charts and tables that Kahn used in his lectures.

“On Thermonuclear War” (Bruce-Briggs suggests that the title, an allusion to Clausewitz’s “On War,” was devised by the publisher) is based on two assertions. The first is that nuclear war is possible; the second is that it is winnable. Most of the book is a consideration, in the light of these assumptions, of possible nuclear-war scenarios. In some, hundreds of millions die, and portions of the planet are uninhabitable for millennia. In others, a few major cities are annihilated and only ten or twenty million people are killed. Just because both outcomes would be bad on a scale unknown in the history of warfare does not mean, Kahn insists, that one is not less bad than the other. “A thermonuclear war is quite likely to be an unprecedented catastrophe for the defender,” as he puts it. “But an ‘unprecedented’ catastrophe can be a far cry from an ‘unlimited’ one.” The opening chapter contains a table titled “Tragic but Distinguishable Postwar States.” It has two columns: one showing the number of dead, from two million up to a hundred and sixty million, the other showing the time required for economic recuperation, from one year up to a hundred years. At the bottom of the table, there is a question: “Will the survivors envy the dead?”

Kahn believed—and this belief is foundational for every argument in his book—that the answer is no. He explains that “despite a widespread belief to the contrary, objective studies indicate that even though the amount of human tragedy would be greatly increased in the postwar world, the increase would not preclude normal and happy lives for the majority of survivors and their descendants.” For many readers, this has seemed pathologically insensitive. But these readers are missing Kahn’s point. His point is that unless Americans really do believe that nuclear war is survivable, and survivable under conditions that, although hardly desirable, are acceptable and manageable, then deterrence has no meaning. You can’t advertise your readiness to initiate a nuclear exchange if you are unwilling to accept the consequences. ...

The most infamous pages in “On Thermonuclear War” concern survivability. What makes nuclear war different, Kahn points out, is not the number of dead; it’s a new element—the problem of the postwar environment. In Kahn’s view, the dangers of radioactivity are exaggerated. Fallout will make life less pleasant and cause inconvenience, but there is plenty of unpleasantness and inconvenience in the world already. “War is a terrible thing; but so is peace,” he says. More babies might have birth defects after a nuclear war, but four per cent of babies have birth defects anyway. Whether we can tolerate a slightly higher percentage of defective children is a question of trade-offs. “It might well turn out,” Kahn suggests, “that U.S. decision makers would be willing, among other things, to accept the high risk of an additional one percent of our children being born deformed if that meant not giving up Europe to Soviet Russia.”

The book proposes a system for labelling contaminated food so that older people will eat the food that is more radioactive, on the theory that “most of these people would die of other causes before they got cancer.” It advocates providing citizens with hand-held radium dosimeters, which will allow them to measure the radioactivity their own bodies have absorbed. One symptom of radioactive poisoning is nausea, Kahn explains, and, when one person vomits, people around him will start to vomit, convinced that they are dying. If the dosimeter indicates that no one has received more than an acceptable dose of radiation, everyone can stop throwing up and get back to work reconstructing the economy. Kahn dismisses the notion that a society that has just suffered the obliteration of its cities, the contamination of its soil and water, and the massacre of a large portion of its population might lack the civic virtue and moral fibre necessary to rebuild. “It is my belief that if the government has made at least moderate prewar preparations, so that most people whose lives have been saved will give some credit to the government’s foresight, then people will probably rally round,” he writes. “It would not surprise me if the overwhelming majority of the survivors devoted themselves with a somewhat fanatic intensity to the task of rebuilding what was destroyed.” The message of the book seemed to be that thermonuclear war will be terrible but we’ll get over it. ...

In its first three months, “On Thermonuclear War” sold more than fourteen thousand copies. The book received praise from a few prominent disarmament advocates and pacifists: A. J. Muste, Bertrand Russell, and the historian and senatorial candidate H. Stuart Hughes, who called it “one of the great works of our time.” They thought that, by making nuclear exchange seem not only possible but nearly unavoidable, Kahn had, intentionally or not, presented a case for disarmament. Not only pacifists believed this. “If I wanted to convince a skeptic that there is no security in the balance of terror which American policy is committed to maintaining, I would send him to the works of Herman Kahn far sooner than to the writings of the unilateralists and the nuclear pacifists,” Norman Podhoretz later wrote.

Other reactions were more predictable. The National Review thought that the book was not hard enough on Communism. New Statesman called it “pornography for officers.” The Daily Worker called it “useful.” In Scientific American, James R. Newman, the editor of the popular anthology “The World of Mathematics,” said that it was “a moral tract on mass murder: how to plan it, how to commit it, how to get away with it, how to justify it.” Though Kahn’s book is an assault on the overwhelming-force mentality of Dulles and the generals at the Strategic Air Command (who, Kahn once told them, dreamed of a “wargasm”), it is also an attack on the anti-nuclear movement and the belief that nuclear war means the end of life as we know it. Most anti-nuclear advocates thought that arguing that a nuclear war was winnable only made one more likely. An official of the American Friends Service Committee compared Kahn to Adolf Eichmann, and he became one of the movement’s favorite monsters. His house was picketed.

The best-known response to “On Thermonuclear War” was a movie. Stanley Kubrick began reading intensively on nuclear strategy soon after he finished directing “Lolita,” in 1962. His original plan was to make a realistic thriller. One of his working titles was taken from an article by Wohlstetter in Foreign Affairs, in 1959: “The Delicate Balance of Terror” (an article that anticipated many of Kahn’s arguments in “On Thermonuclear War”). But Kubrick could not invent a plausible story in which a nuclear war is started by accident, so he ended up making a comedy, adapted from a novel, by a former R.A.F. officer, called “Red Alert.”

“The movie could very easily have been written by Herman Kahn himself,” Midge Decter wrote in Commentary when “Dr. Strangelove” came out, in 1964. This was truer than she may have known. Kubrick was steeped in “On Thermonuclear War”; he made his producer read it when they were planning the movie. Kubrick and Kahn met several times to discuss nuclear strategy, and it was from “On Thermonuclear War” that Kubrick got the term “Doomsday Machine.” The Doomsday Machine—a device that automatically decimates the planet once a nuclear attack is made—was one of Kahn’s heuristic fictions. (The name was his own, but he got the idea from “Red Alert,” which he, too, had admired.) In Kahn’s book, the Doomsday Machine is an example of the sort of deterrent that appeals to the military mind but that is dangerously destabilizing. Since nations are not suicidal, its only use is to threaten. “The whole point of the Doomsday Machine is lost if you keep it a secret!” as Strangelove complains to the Soviet Ambassador.

There were a number of possible models for the character of Strangelove (who at one point tells the President about a report on Doomsday Machines prepared by the Bland Corporation): Wernher von Braun, Teller, even Henry Kissinger, who was an admirer of “On Thermonuclear War,” and whose book “Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy” (1957) pondered the possibility of tactical nuclear wars. Peter Sellers picked up the accent from the photographer Arthur Fellig, known as Weegee, when he was visiting the studio to advise Kubrick on cinematographic matters. But one source was Kahn. Strangelove’s rhapsodic monologue about preserving specimens of the race in deep mineshafts is an only slightly parodic version of Kahn. There were so many lines from “On Thermonuclear War” in the movie, in fact, that Kahn complained that he should get royalties. (“It doesn’t work that way,” Kubrick told him.) Kahn received something more lasting than money, of course. He got himself pinned in people’s minds to the figure of Dr. Strangelove, and he bore the mark of that association forever.

The subject of the Doomsday Machine made an odd reappearance a couple of months ago in Slate - The Return of the Doomsday Machine? - with the article suggesting it may have been real - and perhaps still is. More game theory being played as part of the "new cold war", perhaps ?

The subject of the Doomsday Machine made an odd reappearance a couple of months ago in Slate - The Return of the Doomsday Machine? - with the article suggesting it may have been real - and perhaps still is. More game theory being played as part of the "new cold war", perhaps ?"The nuclear doomsday machine." It's a Cold War term that has long seemed obsolete.

And even back then, the "doomsday machine" was regarded as a scary conjectural fiction. Not impossible to create—the physics and mechanics of it were first spelled out by U.S. nuclear scientist Leo Szilard—but never actually created, having a real existence only in such apocalyptic nightmares as Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove.

In Strangelove, the doomsday machine was a Soviet system that automatically detonated some 50 cobalt-jacketed hydrogen bombs pre-positioned around the planet if the doomsday system's sensors detected a nuclear attack on Russian soil. Thus, even an accidental or (as in Strangelove) an unauthorized U.S. nuclear bomb could set off the doomsday machine bombs, releasing enough deadly cobalt fallout to make the Earth uninhabitable for the human species for 93 years. No human hand could stop the fully automated apocalypse.

An extreme fantasy, yes. But according to a new book called Doomsday Men and several papers on the subject by U.S. analysts, it may not have been merely a fantasy. According to these accounts, the Soviets built and activated a variation of a doomsday machine in the mid-'80s. And there is no evidence Putin's Russia has deactivated the system.

Instead, something was reactivated in Russia last week. I'm referring to the ominous announcement—given insufficient attention by most U.S. media (the Economist made it the opening of a lead editorial on Putin's Russia)—by Vladimir Putin that Russia has resumed regular "strategic flights" of nuclear bombers. (They may or may not be carrying nuclear bombs, but you can practically hear Putin's smirking tone as he says, "Our [nuclear bomber] pilots have been grounded for too long. They are happy to start a new life.") ...

Moving back to The Fat Man, Kahn himself continued writing after he left RAND, and published a number of books during his time at the Hudson Institute, one of which I read a couple of months back called "The Next 200 Years" which he wrote in 1976.

"200 Years" was a reaction against what Kahn called the "doomsday literature" (which was rather ironic, given his background) of the neo-Malthusians, as expressed in The Limits To Growth, The Population Bomb and other similar books, and the "current malaise" the world was experiencing at the time. The RAND Corporation still includes the book in their list of "50 Books for Thinking About the Future Human Condition".

This is a companion piece to Kahn’s book on the year 2000. In it he basically responds to the doom-and-gloom scenario that was laid out in the famous Limits to Growth study from the Club of Rome. Kahn argues that population is the primary driver of the longer-range future and that high world population growth rates around 1976 were an anomaly when looking at historic rates. He thought that the population growth rates would decline after 1976 (which they have) and that would make all the difference. He argues at length that if population levels off at about 15 billion people (probably a high estimate in today’s thinking) that the major problems addressed by the Limits to Growth study could be handled by technology. For those who think that population is the primary driver of the world’s problems, this is a well-argued screed for creating a sustainable earth if we can get population under control. In any event, this book is useful for its serious attempt at looking as far as 200 years into the future.

The book looks at the issue of growth and how it might be handled in 5 main areas - population, energy, raw materials (minerals in particular), food and the environment - in some ways it could be looked at as a deliberately optimistic thought experiment in dealing with the Limits To Growth, rather than denying they exist entirely.

As I go on about the subject of energy every day I won't say too much about that aspect here. Kahn argues that energy will go from an exhaustible resource (ie. a largely fossil fuel based one) to inexhaustible resource (one based on renewable - or what he calls "long term" - sources). To his credit he bites the bullet (possibly against his own personal preferences) and considers the scenario where you simply accept that the days of fossil fuels are numbered (without quibbling over how much oil, coal and gas is actually available) and ignore the nuclear power option because of its drawbacks, and instead try to work out if you can transition to a state where everything is based on solar power (including derivatives such as wind, bioconversion and ocean power), geothermal power and increased energy efficiency. He concludes that there is abundant energy available from these sources and we should be in a position to have transitioned to these by 2050 (which is basically the same conclusion I reached after a year or two of looking at the subject).

Of course, when modelling energy usage, you need to consider both expected population levels and their consumption levels. Kahn was fervently against "Population Bomb" style doomerism and believed the population would plateau around 15 billion people in 200 years time, while noting that exponential growth could and would not continue, and that population growth was already slowing at the time the book was written and that he expected it to slow further and further over time (while insisting that this was not happening because any physical limit to growth had been reached).

Now segments of the peak oil world tends to have a markedly different view on future population trends (with some of the most unpleasant being those of the "internet age's ultimate neo-malthusian" Jay Hanson and his Die Off - "a population crash resource page" - site and its equally toxic successor, the national socialist "War Socialism" site).

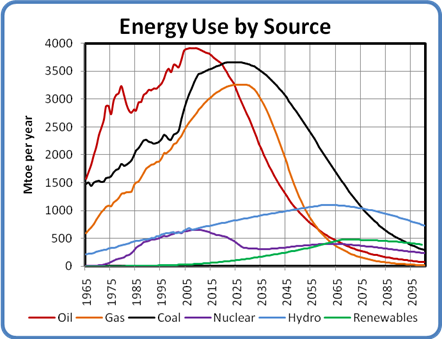

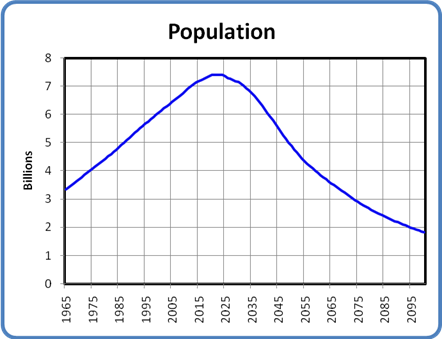

As I've delivered my highly unfavourable verdict on these before, I'll look elsewhere for a good example of the "peak oil = population crash" line of thought - this article at TOD Canada on "World Energy and Population: Trends to 2100" fits the bill nicely.

Throughout history, the expansion of human population has been supported by a steady growth in our use of high-quality exosomatic energy. The operation of our present industrial civilization is wholly dependent on access to a very large amount of energy of various types. If the availability of this energy were to decline significantly it could have serious repercussions for civilization and the human population it supports.

This paper constructs production models for the various energy sources we use and projects their likely supply evolution out to the year 2100. The full energy picture that emerges is then translated into a population model based on an estimate of changing average per-capita energy consumption over the century. Finally, the impact of ecological damage is added to the model to arrive at a final population estimate.

This model, known as the "World Energy and Population" model, or WEAP, suggests that the world's population will decline significantly over the course of the century. ...

The population model is based mainly on the long-term aggregate effects of energy decline. The mechanisms of the population decline it projects are not specified. However, it is likely that they will include such things as major regional food shortages, a spread of diseases due to a loss of urban medical and sanitation services and an increase in deaths due to exposure to heat and cold.

The main interaction in the model is between the energy available at any point in time (shown in Figure 13) and an estimate of average global per capita consumption. Current global consumption is about 1.7 toe per person per year, and in the model that declines evenly to a consumption of 1.0 toe per person per year by 2100. To put that in perspective, the world average in 1965 was 1.2, so the model is not predicting a huge decline below that level of consumption. An increase in the disparity between rich and poor nations is also likely, but that effect is masked by this approach.

Under those assumptions, the world population would rise to about 7.5 billion in 2025 before starting an inexorable decline to 1.8 billion by 2100. ...

Now my personal view is that this is a gross underestimate of how much renewable energy we can and will exploit, which therefore invalidates the conclusions entirely. The link between population growth and available energy possibly isn't quite as clear as many peak oil observers seem to think either - check out this graph from the Buckminster Fuller Institute, which shows an inverse relationship between energy consumption and population growth, as one interesting counter-example.

Recent population models show population leveling off at around 8.9 billion in 2050 (assuming both that fertility rates continue to fall slowly in the developing world, and that efforts to stem the growth of the HIV/AIDS epidemic are successful), though the latest update is now predicting a population level of 9.2 billion, due to slower than expected declines of fertility in developing countries and increasing longevity in richer countries.

For a great visual demonstration of what is happening with family sizes and longevity throughtout the world, watch Hans Rosling's TED Talk from a few years ago (the relevant part starts about 4 minutes in).

I'm fond of quoting Stewart Brand's "4 environmental heresies", one of which is that concern about population growth is unfounded now that it seems likely that it will stall at a level that can be sustainable, with the global population surge into cities driving the drop in growth rates (one of the reasons for my "cities are the future" slogan, even though some people don't seem to be in favour of the idea or misinterpret what is going on).

For 50 years, the demographers in charge of human population projections for the United Nations released hard numbers that substantiated environmentalists' greatest fears about indefinite exponential population increase. For a while, those projections proved fairly accurate. However, in the 1990s, the U.N. started taking a closer look at fertility patterns, and in 2002, it adopted a new theory that shocked many demographers: human population is leveling off rapidly, even precipitously, in developed countries, with the rest of the world soon to follow. Most environmentalists still haven't got the word. Worldwide, birthrates are in free fall. Around one-third of countries now have birthrates below replacement level (2.1 children per woman) and sinking. Nowhere does the downward trend show signs of leveling off. Nations already in a birth dearth crisis include Japan, Italy, Spain, Germany, and Russia -- whose population is now in absolute decline and is expected to be 30 percent lower by 2050. On every part of every continent and in every culture (even Mormon), birthrates are headed down. They reach replacement level and keep on dropping. It turns out that population decrease accelerates downward just as fiercely as population increase accelerated upward, for the same reason. Any variation from the 2.1 rate compounds over time.

That's great news for environmentalists (or it will be when finally noticed), but they need to recognize what caused the turnaround. The world population growth rate actually peaked at 2 percent way back in 1968, the very year my old teacher Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb. The world's women didn't suddenly have fewer kids because of his book, though. They had fewer kids because they moved to town.

Cities are population sinks-always have been. Although more children are an asset in the countryside, they're a liability in the city. A global tipping point in urbanization is what stopped the population explosion. As of this year, 50 percent of the world's population lives in cities, with 61 percent expected by 2030. In 1800 it was 3 percent; in 1900 it was 14 percent.

The environmentalist aesthetic is to love villages and despise cities. My mind got changed on the subject a few years ago by an Indian acquaintance who told me that in Indian villages the women obeyed their husbands and family elders, pounded grain, and sang. But, the acquaintance explained, when Indian women immigrated to cities, they got jobs, started businesses, and demanded their children be educated. They became more independent, as they became less fundamentalist in their religious beliefs. Urbanization is the most massive and sudden shift of humanity in its history. Environmentalists will be rewarded if they welcome it and get out in front of it. In every single region in the world, including the U.S., small towns and rural areas are emptying out. The trees and wildlife are returning. Now is the time to put in place permanent protection for those rural environments. Meanwhile, the global population of illegal urban squatters -- which Robert Neuwirth's book Shadow Cities already estimates at a billion -- is growing fast. Environmentalists could help ensure that the new dominant human habitat is humane and has a reduced footprint of overall environmental impact.

WorldChanging recently commented on some factors that influence population growth, noting that "the number of children a woman bears and raises has an inverse relationship to her - and her children's - life expectancy and social mobility" and thus "improving the availability of family planning options is crucial" (as is encouraging social mobility). In a similar vein, Patrick Di Justo has pointed out the number one factor influencing population growth is education levels for girls - the best way to keep family sizes small is to make sure that girls are able to get a good education. The next most important factors are making sure they have the freedom and economic opportunities to choose what to do with their lives.

Of course, another approach for stabilising population levels instead of providing girls with education, contraception and economic opportunities is simply to legislate controls on the numbers of children people are allowed to have, as per the "one child" policy China introduced in 1979. This has been effective at slowing China's population growth, but due to the Chinese preference for male children, some observers are calling the resulting "surplus of sons" a "geopolitical time bomb".

The Olympics are around the corner. Just as qualifying athletes are training hard for the big event, China seeks to put its best foot forward in response to critics at home and abroad. Among the criticisms is a quiet but serious challenge: the artificially high number of Chinese men compared with Chinese women. China should act expeditiously to correct the social and legal pressures that have converged to create this problem.

"Son preference" is a deep-seated, widespread problem in many cultures. In many parts of the world, having a son is integral to one's future financial and social wellbeing. Recent articles have tried to shed light on the problem in India – putting much blame on the ultrasound machines women use to determine the sex of their unborn children in order to decide whether they should abort a female fetus.

In China, however, the problem takes on a frightfully larger scope when "son preference" meets the notorious One Child policy. When the government only allows one child, it puts immense pressure on Chinese parents to determine the sex of their child in the womb, and terminate the pregnancy if it is a girl.

The unintended consequences of this government policy are staggering. The proportion of male births to female births (the "sex ratio") is not merely unusual, but alarming. Worldwide, there are already 100 million girls "missing" due to sex-selective abortion and female infanticide, according to the English medical journal The Lancet. Fifty million of these girls are thought to be from China. In many provinces, the sex ratio at birth is between 120 to 130 boys for every 100 girls; the natural number is about 104. What will happen in future decades when these boys grow up and look for wives?

Of course, the one child policy will have other side effects as well, leading to a population dominated by the old in future years (which will presumably lead to a relaxation of the one child laws at some point)

China’s population won’t always be the engine of growth that it is now, because the country’s fast-rising proportion of elderly people eventually will drag down the economy, says historian Niall Ferguson in the Los Angeles Times. While China’s population today is relatively young, by the middle of the century it is set to become one of the world’s grayest societies. Today, less than 8% of China’s population is 65 or older. By 2050, that proportion will rise to 24%, compared with Europe’s 28% and 21% in the U.S. In sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of elderly individuals will rise to under 6% from 3% now.

Moreover, at 1.3 billion, China’s population is impressive now, but will be less so in the future. According to U.N. projections, most of the world’s total population increase from 6.5 billion today to 9.2 billion in 2050 will come from sub-Saharan Africa and the Muslim world. India’s population is expected to overtake China’s in 2025. China, whose so-called one-child policy has led to a steep decline in the country’s birth rate in the past several decades, will contribute only 4% of the rise in the world’s population up to 2050.

A high proportion of elderly people generally is thought to crimp economic growth. Certainly, it creates a higher tax burden for workers, who must pay to keep retirees alive. The impact of an aging population on financial markets is more difficult to predict, partly because it depends to what extent retirees save their money or spend it.

Prof. Ferguson, who teaches history and economics at Harvard University, speculates that China might end up aligning itself geopolitically with other countries with aging populations, including the U.S. and European nations. The “Old World” will be made up of countries with high tax rates aimed at ever smaller workforces. Meanwhile, the “Young World” in Africa and India will be marked by youthful unrest and dynamism.

The Economist recently had a look at slowing global population growth, noting some countries are worrying about declining population levels.

The Economist recently had a look at slowing global population growth, noting some countries are worrying about declining population levels.Worries about a population explosion have been replaced by fears of decline

THE population of bugs in a Petri dish typically increases in an S-shaped curve. To start with, the line is flat because the colony is barely growing. Then the slope rises ever more steeply as bacteria proliferate until it reaches an inflection point. After that, the curve flattens out as the colony stops growing.

Overcrowding and a shortage of resources constrain bug populations. The reasons for the growth of the human population may be different, but the pattern may be surprisingly similar. For thousands of years, the number of people in the world inched up. Then there was a sudden spurt during the industrial revolution which produced, between 1900 and 2000, a near-quadrupling of the world's population.

Numbers are still growing; but recently-it is impossible to know exactly when-an inflection point seems to have been reached. The rate of population increase began to slow. In more and more countries, women started having fewer children than the number required to keep populations stable. Four out of nine people already live in countries in which the fertility rate has dipped below the replacement rate. Last year the United Nations said it thought the world's average fertility would fall below replacement by 2025. Demographers expect the global population to peak at around 10 billion (it is now 6.5 billion) by mid-century.

As population predictions have changed in the past few years, so have attitudes. The panic about resource constraints that prevailed during the 1970s and 1980s, when the population was rising through the steep part of the S-curve, has given way to a new concern: that the number of people in the world is likely to start falling.

Some regard this as a cause for celebration, on the ground that there are obviously too many people on the planet. But too many for what? There doesn't seem to be much danger of a Malthusian catastrophe. Mankind appropriates about a quarter of what is known as the net primary production of the Earth (this is the plant tissue created by photosynthesis)-a lot, but hardly near the point of exhaustion. The price of raw materials reflects their scarcity and, despite recent rises, commodity prices have fallen sharply in real terms during the past century. By that measure, raw materials have become more abundant, not scarcer. Certainly, the impact that people have on the climate is a problem; but the solution lies in consuming less fossil fuel, not in manipulating population levels.

Nor does the opposite problem-that the population will fall so fast or so far that civilisation is threatened-seem a real danger. The projections suggest a flattening off and then a slight decline in the foreseeable future.

If the world's population does not look like rising or shrinking to unmanageable levels, surely governments can watch its progress with equanimity? Not quite. Adjusting to decline poses problems, which three areas of the world-central and eastern Europe, from Germany to Russia; the northern Mediterranean; and parts of East Asia, including Japan and South Korea-are already facing.

Think of twentysomethings as a single workforce, the best educated there is. In Japan (see article), that workforce will shrink by a fifth in the next decade-a considerable loss of knowledge and skills. At the other end of the age spectrum, state pensions systems face difficulties now, when there are four people of working age to each retired person. By 2030, Japan and Italy will have only two per retiree; by 2050, the ratio will be three to two. An ageing, shrinking population poses problems in other, surprising ways. The Russian army has had to tighten up conscription because there are not enough young men around. In Japan, rural areas have borne the brunt of population decline, which is so bad that one village wants to give up and turn itself into an industrial-waste dump.

States should not be in the business of pushing people to have babies. If women decide to spend their 20s clubbing rather than child-rearing, and their cash on handbags rather than nappies, that's up to them. But the transition to a lower population can be a difficult one, and it is up to governments to ease it. Fortunately, there are a number of ways of going about it-most of which involve social changes that are desirable in themselves.

The best way to ease the transition towards a smaller population would be to encourage people to work for longer, and remove the barriers that prevent them from doing so. State pension ages need raising. Mandatory retirement ages need to go. They're bad not just for society, which has to pay the pensions of perfectly capable people who have been put out to grass, but also for companies, which would do better to use performance, rather than age, as a criterion for employing people. Rigid salary structures in which pay rises with seniority (as in Japan) should also be replaced with more flexible ones. More immigration would ease labour shortages, though it would not stop the ageing of societies because the numbers required would be too vast. Policies to encourage women into the workplace, through better provisions for child care and parental leave, can also help redress the balance between workers and retirees.

Some of those measures might have an interesting side-effect. America and north-western Europe once also faced demographic decline, but are growing again, and not just because of immigration. All sorts of factors may be involved; but one obvious candidate is the efforts those countries have made to ease the business of being a working parent. Most of the changes had nothing to do with population policy: they were carried out to make labour markets efficient or advance sexual equality. But they had the effect of increasing fertility. As traditional societies modernise, fertility falls. In traditional societies with modern economies-Japan and Italy, for instance-fertility falls the most. And in societies which make breeding and working compatible, by contrast, women tend to do both.

The Economist also had a look at the aging and shrinking population of Japan - one of the more extreme examples of post-growth population dynamics, along with Russia, which is adopting a number of strange tactics to try and reverse its falling population.

While Western Europe also has a low birth rate and aging population, for now this is being more than offset by immigration. Germany has by far the lowest birth rate on the continent.

While Western Europe also has a low birth rate and aging population, for now this is being more than offset by immigration. Germany has by far the lowest birth rate on the continent.A United Nations report this year called this global aging “a process without parallel in the history of humanity” and predicted that people older than 60 would outnumber those under 15 for the first time in 2047.

The twin forces of rising life expectancy and falling birthrates have accelerated the process. This is apparent from the United States, where policy makers fret over the baby boom generation beginning to retire, to Japan, which has the highest share of people older than 60 in the world. As in Japan, more than a quarter of the population in Italy and Germany is over 60, and the phenomenon extends to Poland and Russia.

Although the German government has begun to address the issue, it was particularly slow out of the blocks in dealing with its low birthrate, and, since 2003, the contraction of its population, in that first year by just 5,000 people, but in 2006 by a 130,000. The German population stands at 82.4 million people.

That was, in part, because almost no debate can proceed unencumbered by the country’s Nazi past. Hitler’s government gave medals to mothers of large families, gold for those with eight or more children. Uneasiness over the parallels kept the subject of encouraging reproduction on the back burner in Germany for years, unlike in France where promoting childbearing has long been government policy.

The UK Daily Telegraph recently had a neo-Malthusian take on the subject of population from historian Niall Ferguson, which looks at the relative rates of growth in population and food production, and the impact of biofuel production on rising food prices - "Worry about bread, not oil".

The great demographer and economist Thomas Malthus was 23-years-old the last time a British summer was this rain-soaked, which was back in 1789. The consequences of excessive rainfall in the late 18th century were predictable. Crops would fail, the harvest would be dismal, food prices would rise and some people would starve. It was no coincidence that the French Revolution broke out the same year. The price of a loaf of bread rose by 88 per cent in 1789 as a consequence of similar lousy weather. Historians of the Left like Georges Lefebvre used to see this as a prime cause of Louis XVI's downfall.

Nine years after that rain-soaked summer, Malthus published his Essay on the Principle of Population. It is an essay we would do well to re-read today. Malthus's key insight was simple but devastating. "Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio," he observed. But "subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio." In other words, humanity can increase like the number sequence 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, whereas our food supply can increase no faster than the number sequence 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. We are, quite simply, much better at reproducing ourselves than feeding ourselves.

Malthus concluded from this inexorable divergence between population and food supply that there must be "a strong and constantly operating check on population". This would take two forms: "misery" (famines and epidemics) and "vice", by which he meant not only alcohol abuse but also contraception and abortion (he was, after all, an ordained Anglican minister). "The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation," wrote Malthus in an especially doleful passage of the first edition of his Essay. "They are the precursors in the great army of destruction; and often finish the dreadful work themselves. "But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and tens of thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world."

I wish I could have a free lunch for every time I've heard someone declare: "Malthus was wrong." Superficially, it is true, mankind seems to have broken free of the Malthusian trap. The world's population has increased by a factor of more than six since Malthus's time, passing the 6 billion mark not so long ago. Average life expectancy has risen worldwide from 28 to 67.

Yet the daily supply of calories for human consumption has also gone up on a per capita basis, exceeding 2,700 in the Nineties. In France, on the eve of the Revolution, it was just 1,848. Since Malthus's day, the average human being's income has increased by a factor of more than eight. Human beings have grown taller and bigger, too. The average British male stood 5ft 5in tall in the late 18th century. Today, his mean height is 5ft 9in. So abundant is food in the land of the free that more than a fifth of Americans are now classified as obese.

The conventional explanation for our seeming escape from Malthus is the succession of revolutions in global agriculture, culminating in the post-war "Green Revolution" and the current wave of genetically modified crops. Since the Fifties, the area of the world under cultivation has increased by roughly 11 per cent, while yields per hectare have increased by 120 per cent. In 2004, world cereal production passed the 2 billion metric ton mark.

Yet these statistics don't disprove Malthus. As he said, food production could increase only at an arithmetical rate, and a chart of world cereal yields since 1960 shows just such a linear progression, from below one and a half metric tons to around three. Meanwhile, vice and misery have been operating just as Malthus foresaw to prevent the human population from exploding geometrically.

On the one hand, contraception and abortion have been employed to reduce family sizes. On the other hand, wars, epidemics, disasters and famines have significantly increased mortality. Together, vice and misery have ensured that the global population has grown at an arithmetic rather than a geometric rate. Indeed, they've managed to reduce the rate of population growth from 2.2 per cent per annum in the early Sixties to around 1.1 per cent today.

The real question is whether we could now be approaching a new era of misery. Even at an arithmetic rate, the United Nations expects the world's population to pass the 9 billion mark by 2050. But can world food production keep pace? Plant physiologist Lloyd T Evans has estimated that "we must reach an average yield of four tons per hectare… to support a population of 8 billion". But yields right now are, as we have seen, just three tons per hectare. And a world of eight billion people may be less than 20 years away. Meanwhile, man-made forces are conspiring to put a ceiling on food production. Global warming and the resulting climate change may well be increasing the incidence of extreme weather events as well as inflicting permanent damage on some farming regions.

It is not just British crops that are suffering this year. At the same time, our effort to slow global warming by switching from fossil fuels to bio-fuels is taking large tracts of land out of food production. According to the OECD, American output of corn-based ethanol and European consumption of oilseeds for bio-fuels will double by 2016. Only the other day, the executive director of the World Food Programme expressed anxiety about the unintended consequences of this huge shift of resources.

Some people worry about peak oil. I worry more about peak grain. The fact is that world per capita cereal production has already passed its peak, which was back in the mid-Eighties, not least because of collapsing production in the former Soviet Union and sub-Saharan Africa. Simultaneously, however, rising incomes in Asia are causing a surge in worldwide food demand.

Already the symptoms of the coming food shortage are detectable. The International Monetary Fund recorded a 23 per cent rise in world food prices during the last 18 months. Maybe you've observed it yourself. I certainly have. Of course, we're not supposed to notice that prices are going up. In the United States, the monetary authorities insist that we should focus on the "core" Consumer Price Index, which excludes the cost of food. According to that measure, the annual inflation rate in the US is just 2.2 per cent. But food inflation is roughly double that.

It's a similar story in Britain. Officially, UK inflation was running at 2.4 per cent in June. But food accounts for just 10.3 per cent of the notional basket of goods on which the CPI is based. Food inflation is actually 4.8 per cent. And it gets worse. When I wanted a Philly cheese steak in the States last week, I had to pay through the nose. That's because cheese inflation is 4 per cent, steak inflation is 6 per cent and bread inflation is 10 per cent. (American steak is now 53 per cent dearer than it was 10 years ago.) It was even worse when I fancied fish and chips for lunch on my return to Britain. That's because the fish inflation rate is currently 11 per cent in the UK, closely followed by the potato inflation rate of 10 per cent.

"The great question now at issue," Malthus asked more than 200 years ago, "is whether man shall henceforth start forwards with accelerated velocity towards illimitable, and hitherto unconceived improvement, or be condemned to a perpetual oscillation between happiness and misery." For a long time we have deluded ourselves that "illimitable improvement" was attainable. As the world approaches a new era of dearth, expect misery - and its old companion vice - to make a mighty Malthusian comeback.

The "green revolution" mentioned by Ferguson (and, cryptically, by Alexander Cockburn at the beginning of this post) was the progeny of Norman Borlaug, who was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor earlier in the year, prompting a tribute in the Wall Street Journal on the topic of "Borlaug's Revolution".

In 1944, when Norman Borlaug arrived in Mexico, the nation was in the grip of crop failure. Cereals like wheat are dietary staples. But in Mexico, an airborne fungus was causing an epidemic of "stem rust," and acreage once flush with golden wheat and maize yielded little more than sunbaked sallow weeds. Coupled with a population surge, famine seemed in the offing.

Dr. Borlaug left Mexico in 1963 with a harvest six times what it was when he arrived. From acres of arable land sprung a hyperactive strain of wheat engineered by the scientist in his laboratory, fertilized and nurtured according to his methods, and irrigated by systems he helped to design. Mexico's peasantry was not only fed -- it was selling wheat on the international market. [Norman Borlaug]

The reversal of the Mexican crop disaster was an early tiding of the Green Revolution. Over the next 30 years, Dr. Borlaug devoted himself to the undeveloped world, undoing crop failure in India and Pakistan, and rescuing rice in the Philippines, Indonesia and China. He has arguably saved more lives than anyone in history. Maybe one billion.

Dr. Borlaug was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, yet his name remains largely unknown. Today, at age 93, he receives the Congressional Gold Medal. Perhaps it will secure the fame he merits but never pursued. Then again, perhaps not. While Dr. Borlaug was expanding human possibility, his critics -- who held humanity to be profligate and the Earth's resources finite -- were receiving all the attention. They still are.

The most famous may be Paul Ehrlich, a biologist who declared in the 1960s that "the battle to feed all of humanity" was lost. "In the 1970s and 1980s," he claimed, "hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now." In 1973, Lester Brown, founder of the Earth Policy Institute and still widely quoted today, said the demand for food had "outrun the productive capacity of the world's farmers." The only solution? "We're going to have to restructure the global economy." Of course.

Greenpeace and other pessimists were scandalized at Dr. Borlaug's Green Revolution; it disproved their admonitions and, worst of all, led to industrial development. They even convinced the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations to stop funding Dr. Borlaug's efforts. We see these battle lines today in the energy wars. History has its share of tragedy, but Dr. Borlaug's life demonstrates that environmental doomsayers are almost always wrong because they overlook one variable: human ingenuity.

The late economist Julian Simon was in the habit of claiming that natural resources are basically infinite. His refrain: "A higher price represents an opportunity that leads inventors and businesspeople to seek new ways to satisfy the shortages. Some fail, at cost to themselves. A few succeed, and the final result is that we end up better off than if the original shortage problems had never arisen."

As anti-development environmentalists preach the gospel of limits and state coercion, here is a question worth asking: How many millions of people might have perished had Norman Borlaug heeded their teachings?

The WSJ also had an article by Ronald Bailey about Borlaug last year, noting that, like Al Gore this year, Borlaug also won the Nobel Peace Prize - "The Man Who Fed the World ".

Who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970? You may be forgiven for not remembering, given some of the prize's dubious recipients over the years (e.g., Yasser Arafat). Well, then: Who has saved perhaps more lives than anyone else in history? The answer to both questions is, of course, Norman Borlaug. ...

After graduating from the University of Minnesota in 1944, Mr. Borlaug accepted an invitation from the Rockefeller Foundation to work on a project to boost wheat production in Mexico. At the time, Mexico was importing a good share of its grain. Working at plant breeding stations near Mexico City in the south and near Obregon in the northwestern part of the country, Mr. Borlaug and his staff spent nearly 20 years breeding the high-yield dwarf wheat that sparked the Green Revolution. (Using two stations allowed them to plant two crops a year instead of one, doubling the speed of research.) The key to their success was painstakingly cross-breeding thousands of wheat varieties to find those resistant to highly destructive "rust" fungi. They also changed the architecture of the wheat, from tall gangly stems to shorter sturdier ones that produced more grain.

It was an achievement that made Mexico self-sufficient in wheat by the late 1950s and, when later deployed throughout much of the developing world, forestalled the mass starvation predicted by neo-Malthusians. In the late 1960s, lest we forget, most experts were speaking of imminent global famines in which billions of people would perish. "The battle to feed all of humanity is over," biologist Paul Ehrlich famously wrote in "The Population Bomb," his 1968 best seller. "In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now."

As Mr. Ehrlich was making his dark predictions, Mr. Borlaug was embarking on just such a crash program. Working with scientists and administrators in India and Pakistan, he succeeded in getting his highly productive dwarf wheat varieties to hundreds of thousands of South Asian peasant farmers. These varieties resisted a wide spectrum of plant pests and diseases and produced two to three times more grain than traditional varieties.

Mr. Borlaug's achievement was not confined to the laboratory. He insisted that governments pay poor farmers world prices for their grain. At the time, many developing nations--eager to supply cheap food to their urban citizens, who might otherwise rebel--required their farmers to sell into a government concession that paid them less than half of the world market price for their agricultural products. The result, predictably, was hoarding and underproduction. Using his hard-won prestige as a kind of platform, Mr. Borlaug persuaded the governments of Pakistan and India to drop such self-defeating policies.

Fair prices and high doses of fertilizer, combined with new grains, changed everything. By 1968 Pakistan was self-sufficient in wheat, and by 1974 India was self-sufficient in all cereals. And the revolution didn't stop there. Researchers at a research institute in the Philippines used Mr. Borlaug's insights to develop high-yield rice and spread the Green Revolution to most of Asia. As with wheat, so with rice: Short-stalked varieties proved more productive. They devoted relatively more energy to making grain and less to making leaves and stalks. And they were sturdier, remaining harvestable when traditional varieties--with heavy grain heads and long, slender stalks--had collapsed to the ground and begun to rot.

Hence the Nobel Prize. The chairman of the Nobel committee explained why it had chosen Mr. Borlaug in this way: "More than any other single person of this age, [he] has helped to provide bread for a hungry world. We have made this choice in the hope that providing bread will also give the world peace."

Whether bread induces peace is a question for another day. It certainly kills hunger and saves lives. Contrary to Mr. Ehrlich's bold pronouncement, hundreds of millions of people did not die for lack of food. Far from it. Despite occasional local famines caused by armed conflicts or political mischief, food is more abundant and cheaper today than ever before in history. It is an absurd travesty that Mr. Ehrlich is still much better known than Mr. Borlaug, but perhaps Mr. Hesser's biography can begin to right the balance.

Borlaug himself wrote an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal last year on the subject of "Continuing the Green Revolution", in which he discusses the need for a "Gene" revolution to continue to improve crop yields.

Persistent poverty and environmental degradation in developing countries, changing global climatic patterns, and the use of food crops to produce biofuels, all pose new and unprecedented risks and opportunities for global agriculture in the years ahead.

Agricultural science and technology, including the indispensable tools of biotechnology, will be critical to meeting the growing demands for food, feed, fiber and biofuels. Plant breeders will be challenged to produce seeds that are equipped to better handle saline conditions, resist disease and insects, droughts and waterlogging, and that can protect or increase yields, whether in distressed climates or the breadbaskets of the world. This flourishing new branch of science extends to food crops, fuels, fibers, livestock and even forest products.

Over the millennia, farmers have practiced bringing together the best characteristics of individual plants and animals to make more vigorous and productive offspring. The early domesticators of our food and animal species -- most likely Neolithic women -- were also the first biotechnologists, as they selected more adaptable, durable and resilient plants and animals to provide food, clothing and shelter.

In the late 19th century the foundations for science-based crop improvement were laid by Darwin, Mendel, Pasteur and others. Pioneering plant breeders applied systematic cross-breeding of plants and selection of offspring with desirable traits to develop hybrid corn, the first great practical science-based products of genetic engineering.

Early crossbreeding experiments to select desirable characteristics took years to reach the desired developmental state of a plant or animal. Today, with the tools of biotechnology, such as molecular and marker-assisted selection, the ends are reached in a more organized and accelerated way. The result has been the advent of a "Gene" Revolution that stands to equal, if not exceed, the Green Revolution of the 20th century.

Consider these examples:

* Since 1996, the planting of genetically modified crops developed through biotechnology has spread to about 250 million acres from about five million acres around the world, with half of that area in Latin America and Asia. This has increased global farm income by $27 billion annually.

* Ag biotechnology has reduced pesticide applications by nearly 500 million pounds since 1996. In each of the last six years, biotech cotton saved U.S. farmers from using 93 million gallons of water in water-scarce areas, 2.4 million gallons of fuel, and 41,000 person- days to apply the pesticides they formerly used.

* Herbicide-tolerant corn and soybeans have enabled greater adoption of minimum-tillage practices. No-till farming has increased 35% in the U.S. since 1996, saving millions of gallons of fuel, perhaps one billion tons of soil each year from running into waterways, and significantly improving moisture conservation as well.

* Improvements in crop yields and processing through biotechnology can accelerate the availability of biofuels. While the current emphasis is on using corn and soybeans to produce ethanol, the long- term solution will be cellulosic ethanol made from forest industry by- products and products.

However, science and technology should not be viewed as a panacea that can solve all of our resource problems. Biofuels can reduce dependence on fossil fuels, but are not a substitute for greater fuel efficiency and energy conservation. Whether we like it or not, gas- guzzling SUVs will have to go the way of the dinosaurs.

So far, most biotechnology research and development has been carried out by the private sector and on crops and traits of greatest interest to relatively wealthy farmers. More biotechnology research is needed on crops and traits most important to the world's poor -- crops such as beans, peanuts, tropical roots, bananas, and tubers like cassava and yams. Also, more biotech research is needed to enhance the nutritional content of food crops for essential minerals and vitamins, such as vitamin A, iron and zinc.

The debate about the suitability of biotech agricultural products goes beyond issues of food safety. Access to biotech seeds by poor farmers is a dilemma that will require interventions by governments and the private sector. Seed companies can help improve access by offering preferential pricing for small quantities of biotech seeds to smallholder farmers. Beyond that, public-private partnerships are needed to share research and development costs for "pro-poor" biotechnology.

Finally, I should point out that there is nothing magic in an improved variety alone. Unless that variety is nourished with fertilizers -- chemical or organic -- and grown with good crop management, it will not achieve much of its genetic yield potential.

In his book, Herman Kahn looks at the issue of food supply and predicts it will not be an issue (even with the 15 billion odd population level he foresees), as growing demand will be met by:

* the spread of advanced agriculture techniques as practiced at the time - increasing "tillable acreage", multi cropping and increasing yield by using more fertiliser and new grain varieties (ie. the usual green revolution techniques)

* the introduction of new industrial agriculture techniques in the coming decades

* the use of promising "unconventional" technologies (advances in hydroponics which he labels "nutrient film techniques")

* the adaptation of dietary tastes and habits to "inexpensive food produced by high technology factories" such as "single cell proteins" (which immediately brought "Soylent Green" to my mind)

This section of the book was by far the most unconvincing in my mind, ignoring the impact of both fossil fuel depletion and soil erosion and depletion on his recommended solutions, as well as alternatives like organic farming techniques and unanticipated future developments like the genetic engineering option. I suspect if Kahn was still around he would be a gung-ho GMO enthusiast though.

Ultra doomer James Lovelock shares some of Kahn's views about food growing techniques even if he is at the opposite of the spectrum on the population issue (and sounds like a crazed prophet with his frequent "end his nigh" declarations - though Lovelock supporters could probably make a strong case that he has made far more of a contribution to science and technology than someone like Kahn who simply talked a lot).

Writers like Richard Manning (The Oil We Eat) and Dale Allen Pfeiffer (Eating Fossil Fuels) have made the case that the green revolution will prove unsustainable as fossil fuels become scarcer in a post peak world, impacting on the availability of fertilisers, pesticides and mechanical planting and harvesting machinery - a common view amongst peak oil observers.

A recent article at The Oil Drum looks at "The Connection Between Food Supply and Energy: What Is the Role of Oil Price?".

Experiments tell us that lack of fertilizer will reduce crop yields and that is exactly what oil prices cause--reduction in fertilizer. Why the difference? Precision application of fertilizer rather than the spray-it-all-over-the-place techniques have begun to come into play, minimizing the effect of lessened fertilizer application--so far. Eventually, even that might not be enough to avoid a drop in crop yield.

With corn, one of the interesting realizations is that a 19th century farm grew about 30 bushels per acre, while today, with our machinery we can grow up to 160 bushels per acre. How this is done needs some explanation. The first thing is that on a modern farm, 30,000 corn plants grow per acre. This is about 1.5 square feet per plant. This simply can't be done without machinery. I am in the process of purchasing a 100-acre farm. Let's say I wanted to plant corn by hand and achieve those densities. At 5 seconds per seed, it would take 41 hours to do one acre. And 173 days to do the farm. Of course, by having lots of children I can put them to work. With 10 children, I could do it in 17 days. This shows that without machinery, the plant densities will drop. A modern wheat field has 1.3 million plants. Clearly, without machinery, this is a throw-the-seed-out-there-and-hope-the-birds-don't-eat-it-all exercise.

So, having shown the problem of planting without machinery, we can see that any reduction of oil is likely to cause a serious drop in crop yield, leading to famine. When we can only drive our tractors 80% as much as we do today, it will effectively mean only 80% of the land will be under cultivation. And like everything else, we are being squeezed from two sides. The population increase requires a higher rather than a lower yield per acre. A recent article The Telegraph spoke of this problem. After pointing out that since the 1950s, there has been an 11 percent increase in cultivatable land, yields have gone up 120 per cent. As they say, 'they aren't making new land anymore'.

Its worth noting that if (as Kahn and I both believe) that we can replace our energy needs that are derived from fossil fuels with renewable sources, then much of this argument is invalidated. A shift to a renewable energy based economy means that we can divert remaining oil, gas and coal supplies to the production of fertiliser, pesticides and the like instead of fuel, which changes the scenario outlined dramatically (without even considering alternative means of achieving the required agricultural productivity such as the biotech option mentioned above by Borlaug, or by organic farming techniques that I'll mention later).

The BBC had a series of articles on the state of food production and consumption across the globe, including interesting pieces on The end of India's green revolution? and The limits of a Green Revolution?.

The BBC had a series of articles on the state of food production and consumption across the globe, including interesting pieces on The end of India's green revolution? and The limits of a Green Revolution?. On his farm just outside the Punjabi city of Ludhiana in northern India, Jagjit Singh Hara showed off his collection of old photos. One of the farmer's most prized snaps is of him with the Norwegian-American agronomist Norman Borlaug, the man popularly known as The Father of the Green Revolution. "Here we are when we were both young men," says Mr Singh Hara with smile. "I said to him: 'Dr Borlaug, I want to put my hand in your pocket. But I don't want to take out the dollars, I want to take out the wheat seeds you have.'"

Punjab State, the breadbasket of India, is one of the places where the Green Revolution began. It more than doubled aggregate production here of wheat and rice.

India, a country that will probably soon overtake China as the most populous nation in the world, went from being a food-aid "basket case" to being largely self-sufficient in food. The benefits - and costs - of the Green Revolution in India are reflected in other parts of the developing world. In Punjab, I was looking for clues about whether output could be boosted further to cope with the rising demand that will be required to feed a world population set to rise from 6.6 billion today to more than nine billion people by 2050.

Food output across the world increased considerably in the last four decades of the 20th Century, largely as a result of the intensive farming techniques introduced by the Green Revolution. The new techniques involved distributing hybrid grain seeds - mainly wheat, rice and corn. The hybrids grow with a shorter stalk. This maximises the process of photosynthesis, which nourishes the grain because less energy goes into the stem. The hybrid seeds were combined with the intensive use of fertilisers and irrigation.

Population v Production

After successfully being introduced in India, the Green Revolution was rolled out in other parts of Asia, Latin America and the Middle East. It was so successful in terms of production increases that it defied the gloomy Malthusian predictions of the 1960s, which said hundreds of millions would starve as population outstripped farm output.

The Revolution was a technological success. "Before the 1960s, the population of India was multiplying like rats in a barn," said Jagjit Singh Hara, "but we didn't have the grain to feed them. After the Green Revolution, we doubled our yield and now we have proved that India can feed the world".

But the process has limits and they may have been reached. Population, on the other hand, has continued to rise in poor parts of the world. The graph, compiled for the BBC by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, shows that while yield per hectare has increased, the amount of land used for the major staple grains has remained fairly constant; this is because the amount of good farmland is finite.

Given the shortage of land suitable for growing more food, the obvious answer would be a new Green Revolution, or another hike in yields. But this may not be possible. "The difficulty is that we are now pressing against the photosynthetic limits of plants," says the influential environmentalist Lester Brown of the Earth Policy Institute in the United States. ...

There are other limits to the Green Revolution. Some of the poorer villagers I spoke to in rural Punjab said they had fallen into debt as they were unable to keep up with the rising cost of the inputs - fertilisers, irrigation pumps and regular fresh supplies of seed - which intensive agriculture requires. One elderly man in the village of Lehragaga, Jasram Singh, sat on an old iron bedstead in his yard and recounted the unbearable pain he had suffered when two of his sons had committed suicide. They had fallen into debt, been forced to sell their land, and felt irreconcilable shame.