The Cathedral And The Bazaar

Posted by Big Gav

Resource Investor has an excellent article on CERA's recent attempted debunking of peak oil courtesy of Petroleum Review's Chris Skrebowski, who is picking the peak date around 2011.

You may remember recently that Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA) produced a report Why the “Peak Oil” Theory Falls Down – Myths, Legends, and the Future of Oil Resources. In the report it rubbished the theory of peak oil before going on to say that “peak oil” will in fact happen.

It did this by saying that there will be no single peak but a series of bumps and bounces they called an “undulating plateau.” This seemed quite odd to many “peak oil” observers as one of the prime theories, or types, of peak oil is in fact an undulating plateau. As opposed to a nice pointy mountain type shaped triangle.

CERA are the analyst group led by Daniel Yergin author of “The Prize” and whose reports go for thousands of dollars. When the report came out we mentioned how odd it was that the ‘peak oil’ crowd were being attacked in this way. Why did such an establishment body need to take so much time attacking a group it sees as so far-out?

Well now it has had a reply. Chris Skrebowski from the Energy Institute in London has written an open letter to CERA wondering about many of the same questions. Skrebowski is in fact a regular ‘peak oil’ chap. He is not given to wild pronouncements and is currently editor of the industry magazine Petroleum Review. This makes what he has to say a lot more interesting.

After some initial jousting Skrebowski notes that CERA’s public denouncement of‘peak oil is not quite as it would seem.

“It is not even clear if CERA believes its own report as I am intrigued to see that CERA is now promoting a new multi-client survey Dawn of a New Age: Global Energy Scenarios for Strategic Decision Making - The Energy Future to 2030. In the promotional blurb we learn in the first paragraph that it is a multi-client study and such gems as “... reflecting the heightened anxiety about the future of energy. The concern is not just over oil, but every aspect of the energy value chain; and the stakes are high for all participants in the global economy - but especially for senior executives and policy makers.”

“Let me see if I’ve got this correct. For a public attack on Peak Oil activists’ concerns you claim there’s not an oil supply problem and we’re all irresponsible alarmists. But for senior executives and policy makers you have ‘undertaken the most comprehensive research project in our history’.”

It is a good point. Energy security, maturing fields and supply questions are openly discussed at many events worldwide. Many senior industry figures believe peak oil will happen at some point, they just do not know when.

There then follows some arguing over reserve estimates, whether all the possible reserves in the world are really possible. But Skrebowski then makes his most interesting point, one that we have pointed out before, that CERA do in fact believe in “peak oil.”

“Now although you regard the Peak Oil community as far too pessimistic I ask you to consider the following. If we take the simplest and most straightforward reserves based approach and use the best figures for proven and probable (2P) reserves from IHS Energy (CERA’s parent company) these show that by end 2005 some 1,077 Gb (billion barrels) had been produced and 1,251 Gb remained, giving total discovered reserves of 2,328 Gb. Now if Peak Oil occurs when 50% of the reserves have been depleted – how long will it be until 1,164 Gb have been produced? Again using IHS Energy figures we are finding a little over 11 Gb/year and consumed 29 Gb in 2005 so our collective net consumption of reserves is 18 Gb/year. On that basis we peak in slightly under 5 years, or in 2012.”

He then goes on to back up our view, that what CERA is doing is providing a blanket of denial for the industry, whilst simultaneously telling the industry itself that the problem is real.

“As you know my personal belief is that an analysis based on new production flows is more accurate. Using all the latest data in my megaprojects (actually all yielding peaks of over 40,000 b/d) I find that Peak Oil occurs in 2011 plus or minus one year.

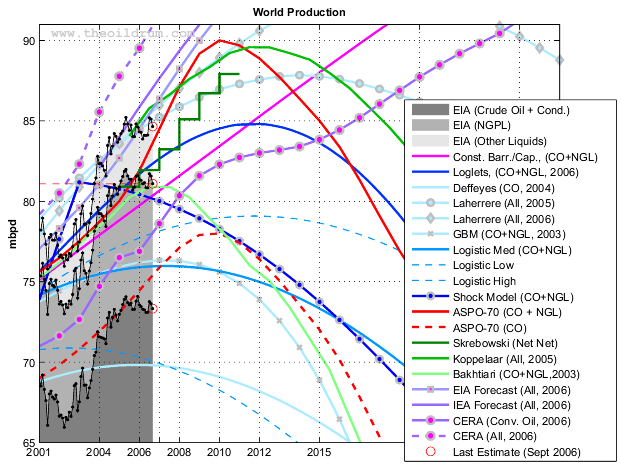

Khebab has another one of his regular roundups of peak oil depletion models up at The Oil Drum.

# IEA forecast (World Energy Outlook, 2006)

# IEA forecast (World Energy Outlook, 2005)

# IEA forecast (World Energy Outlook, 2004)

# Forecasts for Saudi Arabia

The open source modelling and data interpretation done at The Oil Drum is in stark contrast to proprietary analysis done by peak oil naysayers like CERA who use a private data source and then publish their results, available for a large fee, to those who trust their authority on the subject. I think there is a lot of truth to Kurt Cobb's speculation that CERA finds all this public peak oil analysis grating as it undercuts into their credibility and threatens their market share - a classic example of the The Cathedral and the Bazaar.

The Huffington Post has an article on the best strategy to achieve energy security for the US - abandon the Carter doctrine and reduce oil consumption so that external events affecting oil supplies can be safely ignored.

During this holiday season, I bring you tidings of great joy: Finally, an organization in Washington comprised of Americans of standing and competence that is speaking the truth about our precarious supply of oil and what we should do to meet proliferating threats around the world. The only real and lasting solution to energy security, these wise men proclaim, is to change consumption patterns here at home.

Retired Air Force General Charles F. Wald member of the Energy Security Leadership Council of SAFE (Securing America's Energy Future) has returned to Washington with a mission, broadcasting his organization's warning that there's no way America can live up to its promises under the Carter Doctrine -- even if we had the troop strength, which we don't. The 1980 Carter Doctrine outlined our intention to secure Persian Gulf oil from a belligerent and communist Soviet Union...

Wald now finds the Carter Doctrine is obsolete, and thinks the Pentagon needs to devise a more centralized plan for energy security that incorporates all military branches. He is hopeful that new Secretary of Defense Robert Gates will give the issue more attention than Donald Rumsfeld did. But even so, Wald is convinced -- and I share this concern though he knows far better I do-- that no combination of guns and diplomacy can secure the global fuel supply. The threats are simply too diverse, and the will of everyone involved too weak, to keep the danger constantly at bay.

Wald, a veteran of Vietnam, the Balkans, and Afghanistan, spent his final tour of duty as the deputy chief of the U.S. European Command, which also oversees Africa and parts of Central Asia. It's a massive territory that straddles potentially enormous supplies of petroleum, and it didn't take the general long, as Wall Street Journal reporter Chip Cummins wrote this week, to recognize the vulnerabilities for the oil-rich Caspian Sea and West Africa, two of his areas of responsibility. The latter is a rebel-infested area plagued by crime and poverty, while the Caspian region lives in the shadow of an increasingly provocative Russian government not shy about energy saber-rattling. And in reality, of course, the threat of terrorism is virtually omnipresent, existing wherever oil flows.

Wald's organization, SAFE, would have our policy makers clearly understand that in this century the global oil market is far removed from what we hold to be a free and unfettered market. That we must recognize that between 75% and by some estimates 90% of all oil and gas reserves are held by national oil companies, partially or fully controlled by their governments. That in essence oil markets have become largely politicized and that market forces alone will not solve the problems of oil supply and security. Therefore a new definition of energy security is needed, one that relies not on tough military and foreign policy, but on a strategy that emphasizes reduced consumption of oil. It further needs to take into account how global warming might impact U.S. energy and environmental security in the future.

The Kuwait Times has an article on the peaking of the Burgan oil field.

It was an incredible revelation last week that the second largest oil field in the world is exhausted and past its peak output. Yet that is what the Kuwait Oil Company revealed about its Burgan field. The peak output of the Burgan oil field will now be around 1.7 million barrels per day, and not the two million barrels per day forecast for the rest of the field's 30 to 40 years of life, Chairman Farouk Al-Zanki told Bloomberg. He said that engineers had tried to maintain 1.9 million barrels per day but that 1.7 million is the optimum rate. Kuwait will now spend some $3 million a year for the next year to boost output and exports from other fields.

However, it is surely a landmark moment when the world's second largest oil field begins to run dry. For Burgan has been pumping oil for almost 60 years and accounts for more than half of Kuwait's proven oil reserves. This is also not what forecasters are currently assuming.

Last week the International Energy Agency's report said output from the Greater Burgan area will be 1.64 million barrels a day in 2020 and 1.53 million barrels per day in 2030. Is this now a realistic scenario?

The news about the Burgan oil field also lends credence to the controversial opinions of investment banker and geologist Matthew Simmons. His book 'Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy' claims that ageing Saudi oil fields also face serious production falls.

The implications for the global economy are indeed serious. If the world oil supply begins to run dry then the upward pressure on oil prices will be inexorable. For the oil producers this will come as a compensation for declining output, and cushion them against an economic collapse. However, the oil consumers then face a major energy crisis. Industrialized economies are still far too dependent on oil. And the pricing mechanism of declining oil reserves will press them into further diversification of energy supplies, particularly nuclear, wind and solar power.

All this was foreshadowed in the energy crisis of the late 1970s when a serious inflection in oil supply by the year 2000 was clearly forecast. How ironic that those earlier forecasts now look correct, while more modern and recent forecasts begin to look over optimistic and out-of-date with geological reality.

Nobody can change the geology, and forces of nature that laid down reserves of oil and gas over millions and millions of years. Could it be that we have been blinded by technological advances into thinking that there is some way to beat nature?

The natural world has an uncanny ability to hit back at the arrogance of man, and perhaps a reassessment of reality at this point is called for, rather than a reliance on oil statistics that may owe more to political manoeuvring than geological facts.

The UK Daily Telegraph has a report on growing unease about Russia's ability to raise gas prices when it feels like it after the sudden rise in gas prices for Georgia. I'm not quite sure why people are complaining about the price adjustments for former Soviet republics to match what EU countries pay - I would have thought that was normal in a globalised energy market. However the EU (and the pieces of the former Russian Empire) would be well advised to note what Russia could do in future, if they don't work to become independent of Russian energy. The Oil Drum also has a post on what the death of Turkmenbashi could mean for gas supplies from Turkmenistan - the owner of the world's 4th largest gas reserves.

Russia's use of energy supplies as a political weapon should be a wake-up call to Britain and the West to deal urgently with the threat, senior Conservatives said last night. Liam Fox, the shadow defence secretary, stepped up Tory calls for a Nato-style "energy pact" after Gazprom, Russia's state-controlled energy giant, forced the pro-Western former Soviet republic of Georgia to accept a doubling of gas prices.

"While the West has been focused on the Middle East, we have seen the resurgence of Russian nationalism and a willingness to use natural resources as a political weapon," he said. "Given the nature of Russia's political leadership, this is hardly surprising. Following events in Ukraine, and now Georgia, it is high time for a wake-up call to western politicians. We have been warned."

Georgia declared the price increase "unacceptable" and "politically motivated" but was forced to accept when Russia threatened to cut off supplies. Last night the president of Azerbaijan, another former Soviet republic that is being asked to pay twice the price for its gas, accused the Russian company of "ugly" behaviour and said his country would not be bullied into accepting. President Ilham Aliev said that if Moscow insisted on doubling the price of gas to $230 (£117) per thousand cubic metres, Azerbaijan would be forced to "change the balance of power" and rely on its own oil reserves instead. That might mean restricting Azerbaijan's oil exports, which pass through Russia, in order to fuel domestic power stations, he said. Although Azerbaijan produces only half the natural gas it needs, Mr Aliev told a Russian radio station, it would not give in to Moscow. "To take advantage of this deficiency is ugly," he said.

In the first sign of a regional backlash, he attacked Russia's use of energy as a tool of foreign policy, although he was careful not to name or criticise President Vladimir Putin personally. The price of oil and gas should "be a commercial matter", immune from attempts to "politicise it", Mr Aliev said.

The move by the Russian company is being portrayed by the Kremlin as merely bringing the price paid by former Soviet neighbours nearer to the market price paid in western Europe – up to $300 per 1,000 cubic metres. But it has used its clout as a supplier of cut-price energy to try to force its neighbours into line on foreign and economic affairs.

Jeff Vail touches on the Uzbekistan situation in his post on trends for 2007.

So what will this year bring? I've titled this year's predictions "Trending" after what I see as the overarching theme in the coming months: the continuation of existing trends that will create a "trend line" so clear as to increasingly become obvious. It will no longer be possible to hide the facts or to explain them away as some kind of "blip."

Iraq, Iran, and the Great Game: With Niyazov's death, Turkmenistan enters the "toss-up" category and we will see the geopolitical chess match for control in the Middle East acclerate. However, while violence in Iraq will continue to escalate, and the too-late attempts to force a "Battle of Baghdad" by the current administration will fail, we will see the clear emergence of the trend that has already begun to surface: the de-facto division of Iraq into secular enclaves. US forces will finally begin a draw down, though confusion and disagreement is so rife within US policy circles on this topic that we will even fail to effectively chart this course of action in the coming year. Iran will continue to play pragmatist, balancing their own internal politics with nuclear development, bi-lateral energy deals with China, and a careful tightrope dance with the UN Security Council. No war on Iran this year.

Oil Prices: Here's where the trend becomes clear. I'll resist the temptation to "play it safe" and predict an $80 close at the end of '07. Instead, I'll tell you what I think will really happen. "Peak oil" will become a word that is frequently heard on newscasts as it becomes clear that Saudi Production is dropping (no longer hidden behind a veil of "OPEC cuts"). Russian production will also fall, as will Norway, UK, Venezuela, US, Iran, and Mexico (more on that later). As this trend becomes clear, oil prices will quickly reach $90, and may even flirt with $100 before the year is out. It will be impossible to cover these stories as the media blitz surrounding the '08 elections begins to pick up steam, and the media listens to the various politicians who need to emphasize the problem before they can win points with their "solution." Even though the suggested solutions of Ethanol or Hydrogen or drilling of the Pacific Coast don't hold water, they all have the common theme of being more valuable to their respective candidates the worse that the current oil supply situation seems to be. As a result, "peak oil" will officially "tip."

Economy: Housing prices will level off and stagnate in most areas. But it will be with the "fictional economy" of derivatives that we will continue to see growth. The economy will sustain itself as a whole--driven largely by accelerating gains in the energy sector and among the "super rich" that offset the decline in just about everything else. However the most remarkable phenomenon will be the clear trend towards a division between rich an poor. A new, de-facto aristocracy will begin to make its presence felt as the super rich get richer, and the Median American wage gets lower. The dollar will slowly continue to slide, but I don't see a cliff in '07--we'll probably close out the year around $1.42 per Euro.

Mexico: Here's what I'll say is the most sigificant development in '07--the Mexican economy will collapse. Inflation will go on a tear. Cantarell will drop off a cliff (no real surprise here) and Calderon will leverage what little credit Mexico has left investing billions in new development in the Gulf that will never come to fruition--but that will create the same kind of debt crisis in the coming years that we have seen in other South American countries. With oil revenues essentially 0 (when you factor in the increased exploratory spending and borrowing to "develop"), the federal revenues will fall through the floor. When you account for higher airfare due to fuel costs, tourism dollars will dry up as well. As a result, Mexico will go into a tailspin. The full impact of this will not be felt in '07, but the trend towards this fate will become clear. This will also set in motion forces that will begin to tear (further) apart the illusory fabric of the American nation-state: decentralization in Mexico will lead to increasing cross-border "illicit" activity, from human smuggling to drug smuggling to organized crime to black market activites focused around the death of "intellectual property." Not a good year for Mexico, but it will increasinly become clear that this is also a very bad sign for the US, and for thetNation-State as a concept.

Jeff Vail also has a post on the value of Transparency - which is something I hope is going to become an increasingly powerful trend this century (all evidence to the contrary in recent years notwithstanding).

John Robb has an interesting new post called "Radical Transparency to Improve Resiliency." It tackles the same concept that I addressed two years ago in "Open Source Warfare vs. Arcane Use For Power": that "secrecy" is an outmoded symptom of hierarchy, and that focusing instead on accelerating our information processing (via the OODA loop model) and understanding the benefits of transparency within a game-theory model should allow us to move beyond secrecy. Take a look at Robb's article because he provides covereage of this topic from a slighly different perspective--but, interestingly, one that is less "4th-Generation Warfare" centric than his usual posts. Here, his posts directly address economic activities.

I think that the most fascinating part of this whole discussion on transparency vs. secrecy is the prospect that an awareness that processes must move from secretive to transparent may also force them (to some degree) from hierarchal to rhizome. I have long argued that rhizome is a more efficient means of information processing (it just isn't as efficient at accreting benefits to a select few)--perhaps the business world will begin to embrace this? I'm not holding my breath...

**I just can't help but point out, mainly because as someone who is generally not very good at puzzles I'm still rather impressed with myself, that the title of my original post consists of two phrases that are anagrams of each other and ALSO convey the juxtaposition of ideas in conflict therein: OPEN SOURCE WARFARE and ARCANE USE FOR POWER.

I think the comment about the business world is mistaken in viewing the business world as a monolithic entity - while transparency is threatening to some organisations it presents a market opportunity to others. As John Robb says, transparency provides a more resilient, and thus stronger, framework overall for societies and economies to build on - so transparent societies and organisations should tend to out compete non-transparent ones (the West vs the Soviet Union being one early example, even if we seem to have slipped a lot on the transparency front since the communists collapsed).

Jason at Anthropik has a related post called "rhizome ascendent which makes the case that massive hierarchies are failing against distributed, localised forms of organisation.

I have made the case that the kind of structures that Jeff Vail describes as rhizome will emerge less through any kind of awareness of their theoretical superiority, than simple necessity. Long-term trends and historical examples highlight that argument, but it is still exceptional to see three different approaches that so clearly point to the same conclusion, all on the same day. Such a coincidence is worthy of commentary.

John Robb's blog, Global Guerrillas, is always an excellent source of how the "War on Terror" relates to problems of complexity, and how our civilization's increasing complexity represents an increasing probability of catastrophic breakdown. In his most recent brief, "The New Threats," Robb outlines the threats Western civilization faces, and points to the only thing that can save it: increased resilience.The only solution for these problems isn't something that gains much currency from the current decision makers. There isn't any built-in audience ready with money and support to make them happen (at least, not yet). The reason is that systemic resilience is hard. It reverses power relationships and pushes control to the edges. It simplifies processes and builds-in dampening forces to limit the impact of any shocks that ripple through our global network. It forces changes in individual behavior to broaden skill sets and limit dependencies. In short, it isn't anything you will read in any report generated by current or past power brokers.

Faced with a rhizome network, according to Robb, the only means of survival our hierarchical civilization has, is to shed both our hierarchy, and our civilization, to become a rhizome network. This decentralization of power that Robb proposes is collapse, and like any collapse, it would vastly improve the quality of life for nearly all involved.

This quote that Jason uses (from "You Only Link Twice - Spying 2.0" about the "Intellipedia" idea is interesting - I laughed when I originally read about Intellipedia - the concept of a wiki seems to be the complete opposite of these types of information systems, which tend to bind information up tightly with various classifications and caveats and rigidly control who can access it. I can conceive of the wiki form of information gathering being useful within small, relatively focused groups in that sort of environment, but it would still be less agile than the full open source way of doing things if competing groups had access to equivalent sources of information (which historically they haven't but that seems to be changing rapidly).

I first heard stirrings of this kind a few months back in a Reuters news story about Intellipedia. The idea of a wikipedia for spies is so obviously intriguing that it was almost an inevitable story for the magazine. It starts with a similar gambit: a young geek obsessed with tools takes a job at an intel org, expecting to meet Q and learn about the super-hightech terrorist-nabbing tools. Realization: the bloated government bureaucracies, our first line of defense, are struggling with Windows 95 and Netscape 4.0 — or their top-secret equivalents.

But apparently a few young geeks seeking to serve the nation have noticed ... and have started to create the classified equivalent of Web 2.0. The article does a great job of imagining what might have happened (if hindsight=20/20) before 9/11. Were intel agencies actually furiously adding comments to each others blogs, hashing out the meaning of scattered bits and pieces of info, checking technorati and recent changes obsessively, pinging and trackbacking their way into the heart of the plot—well then maybe the course of history might have been different. It’s a nice thought experiment. Of course, the idea raises certain paradoxes: to get such rich information, nearly everyone from the beat cop in Minnesota to the flight school operaters in Arizona to Bond himself, needs to be constantly blogging and updating their tips and infos—0wn1ng the "Al Qaeda plots" page, so to speak. But if they do so in a public forum then the plotters themselves only need check their rss readers to know just what US intel knows. By contrast, keeping the Intellipedia secret reduces its effectiveness the more secret it is. Not only that, but the very problem of terrorism is that we don’t know who are terrorists and who are not—so we have no way to exclude them except to be completely paranoid. Sharing and secrecy each produce their own kind of knowledge/power order. Or as the article puts it "social software doesn’t work if people aren’t social."

Jason closes with some passages from Ralph Peters' "Return of the tribes" in The Weekly Standard of all places, which seems to indicate that it may be dawning on the neocons that world domination could be a little trickier to realise than they imagined.

I'm not a regular reader of The Weekly Standard, the flagship publication of the neoconservative movement, but Ran Prieur's link to Ralph Peters' "Return of the Tribes" was sufficiently intriguing to read in full. Peters is a retired army Lieutenant Colonel, and though he was for a long time an ardent supporter of the Iraq War, the slow failure of that mission seems to have taught him some important lessons. For instance, his proposal for peace in the Middle East recognizes that much of the tension in the region comes from post-colonial borders (deliberately set specifically to create such violence, in order to create a system of neocolonial dependence); his proposal recognizes the regional differences in the region and draws new borders that respect genuine cultural differences.

In this article from September, Peters goes further, counseling the neoconservative audience that so values his advice that globalization is doomed to failure. His article begins:Globalization is real, but its power to improve the lot of humankind has been madly oversold. Globalization enthralls and binds together a new aristocracy--the golden crust on the human loaf--but the remaining billions, who lack the culture and confidence to benefit from "one world," have begun to erect barricades against the internationalization of their affairs. And, from Peshawar to Paris, those manning the barricades increasingly turn violent over perceived threats to their accustomed patterns of life. If globalization represents a liberal worldview, renewed localism is a manifestation of reactionary fears, resurgent faiths, and the iron grip of tradition. Except in the commercial sphere, bet on the localists to prevail.

Not only in the developing world, but even in Europe, Peters finds examples that the trend of history is moving away from integration, into "tribal" identities, with smaller groups identified with a specific ecology. Peters finds a parallel to modern globalization in the universal, monotheistic religions, noting:

When we speak of religion--that greatest of all strategic factors--our vocabulary is so limited that we conflate radically different impulses, needs, and practices. When breaking down African populations for statistical purposes, for example, demographers are apt to present us with a portrait of country X as 45 percent Christian, 30 percent Muslim, and 25 percent animist/native religion. Such figures are wildly deceptive (as honest missionaries will admit). African Christians or Muslims rarely abandon tribal practices altogether, shopping daily between belief systems for the best results. Sometimes, the pastor's counsel helps; other times it's the shaman who delivers. ...

Even as they change their names, the old gods live, and our attempts to export Western ideas and behaviors are destined to end in similar mutations. Our personal bias may be in favor of the frustrated missionaries who try to dissuade the Christians of up-country Sulawesi from holding elaborate, bankrupting funerals with mass animal sacrifices (death remains far more important than birth or baptism), but the reassuring counter is that in the Indonesian city of Solo, where Abu Bakr Bashir established his famed "terrorist school," the devoutly Muslim population drives Saudi missionaries mad by holding a massive annual ceremony honoring the old Javanese Goddess of the Southern Seas. Likewise, Javanese and Sumatran Muslims go on the hajj with great enthusiasm (on government-organized tours), but continue to revere the spirits of local trees, Sufi saints, and the occasional rock.

In Senegal, I found local Muslims irate at the condescending attitudes of Saudi emissaries who condemned their practices as contrary to Islam. With their long-established Muslim brotherhoods and their beloved marabouts, the Senegalese responded, "We were Islamic scholars when the Saudis were living in tents."

From West Africa to Indonesia, an unnoted defense against Islamist extremism is the loyalty Muslims have to the local versions of their faith. No one much likes to be told that he and his ancestors have gotten it all wrong for the last five centuries. Foolish Westerners who insist that Islam is a unified religion of believers plotting as one to subjugate the West refuse to see that the fiercest enemy of Salafist fundamentalism is the affection Muslims have for their local ways. Islamist terrorists are all about globalization, while the hope for peace lies in the grip of local custom.

Peters is advising the same neoconservatives who plot world domination that their dream is fundamentally impossible. Universal aspirations—whether religious or economic—have no grounding, because that would root them in a specific place. It also makes them ephemeral. The magic that people so deeply need can only come from a specific place and a relationship with it—and that means that any globalization scheme will always fragment into smaller and smaller tribes. Salafist terrorists will be undone by the very same "spirit of place" that dooms Western plans of globalization. Peters concludes:Globalization isn't new, but the power of local beliefs, rooted in native earth, is far older. And those local beliefs may prove to be the more powerful, just as they have so often done in the past. From Islamist terrorists fighting to perpetuate the enslavement of women to the Armenian obsession with the soil of Karabakh—from the French rejection of "Anglo-Saxon" economic models to the resistance of African Muslims to Islamist imperialism—the most complex forces at work in the world today, with the greatest potential for both violence and resistance to violence, may be the antiglobal impulses of local societies. From Liège to Lagos, the tribes are back.

Some of the open source enthusiasm embodied in these pieces is redolent of the thinking during the heady days of the tech boom - I'm just getting started on Fred Turner's book "From Counterculture to Cyberculture" and the introduction pretty much sums up much of this line of thinking (which is a little utopian and, like most utopian visions, probably likely to end up in some nasty sort of conflict as the traditional ways of doing things attempt to adapt and reassert themselves).

In the mid-1990s, as first the Internet and then the World Wide Web swung into public view, talk of revolution filled the air. Politics, economics, the nature of the self—all seemed to teeter on the edge of transformation. The Internet was about to "flatten organizations, globalize society, decentralize control, and help harmonize people," as MIT's Nicholas Negroponte put it. The stodgy men in gray flannel suits who had so confidently roamed the corridors of industry would shortly disappear, and so too would the chains of command on which their authority depended. In their place, wrote Negroponte and dozens of others, the Internet would bring about the rise of a new "digital generation"—playful, self-sufficient, psychologically whole—and it would see that generation gather, like the Net itself, into collaborative networks of independent peers. States too would melt away, their citizens lured back from archaic party-based politics to the "natural" agora of the digitized marketplace. Even the individual self, so long trapped in the human body, would finally be free to step outside its fleshy confines, explore its authentic interests, and find others with whom it might achieve communion. Ubiquitous networked computing had arrived, and in its shiny array of interlinked devices, pundits, scholars, and investors alike saw the image of an ideal society: decentralized, egalitarian, harmonious, and free.

Both Jeff and Jason referred to John Robb's post "Radical transparency to improve resilience.

Chris Anderson, the editor of Wired magazine and the author of the new book "The Long Tail," is currently exploring the concept of radical transparency and what it means to media companies. I suggested a similar approach in my "Power to the People" article in Fast Company as a means of improving societal resilience:

A newly vigilant and networked public will push for much greater levels of transparency in government and corporate operations, using the Internet to expose, publish, and patch potential security flaws. Over time, this new transparency, and the wider participation it entails, will lead to radical improvements in government and corporate efficiency.

He lists six tactics media organizations can use to improve their transparency and lists the costs and the benefits. Here's some homework. Think about how these tactics can be applied to societal resilience:

* Show who we are.

* Show what we are working on.

* "Process as Content."

* Privilege the crowd.

* Let readers decide what is best (aka: wisdom of the crowd)

* Wikify (this another way of saying: open the storehouse of background information) everything.

Final thought. Within the context of 21st century warfare, moral cohesion and innovation (particularly given open source opponents) have emerged as paramount concerns. Up until now, nation-states have relied on propaganda to mobilize the public for war and maintain the effort. In parallel, black box decision making has been relied upon to produce ongoing improvements in capabilities/technology. However, in this long war, these methods are more of a liability than an asset. Propaganda has proven to be both ineffective and harmful (see my critique: "Propaganda Wars" for more on this) -- and -- black box decision making has yet to yield any meaningful improvements in capabilities. In my view, an update to our decision making process (to take advantage of vastly superior information flows) through radical transparency would be a far superior means of maintaining our moral cohesion and innovation over the long haul.

John Robb also has posts on "Losing the battle for Baghdad, which looks at the insurgent tactic of shutting down Baghdad's power supply, and a creepy speculative piece on "Breaking Mexico" which I hope doesn't eventuate.

One final relevant post from John Robb is on "The biggest gang in Iraq - which to me simply emphasises the need to transition from oil to electricity for our transports as rapidly as is physically possible - there aren't any good options in the middle east.

US soldier on patrol in Mosul Iraq, "This is like a gang war, and we are the biggest gang."

The US has fully abdicated any attempt at winning in Iraq under any meaningful victory conditions. That route is forfeit, as operations wind down (particularly in Anbar), funding for reconstruction evaporates (Bechtel's departure from Iraq marked the end of the effort), and efforts to rebuild the Iraqi military continue to fail (due to a deficit of loyalty to the government). Despite this, withdrawal from Iraq doesn't appear to be an option. The reason for this is simple and doesn't include shame or a loss of power. It's more basic. It's OIL. Iraq is a core producer of oil for global markets. Control of this oil cannot be ceded to either the guerrillas or Iran under any meaningful current interpretation of US policy. Further, a full US withdrawal would put Saudi Arabia at risk -- the collapse of both of these oil producers in tandem would plunge the global economy into a depression. As a result, the US will inevitably decide to stay. The US political establishment seems to have already defaulted to this decision, as seen by the complete lack of any substantive political discussion about actually leaving Iraq. The most we will likely see is a substantial reduction in troops to take the stress off of the army and assuage critics.

However, a decision to stay isn't a strategy. Given the inability of the current leadership to generate an alternative, the likely default strategy that might be adopted is the the role of the spoiler. This strategy is dedicated to merely preventing any antagonistic regional powers (Iran and Syria) or internal factions from toppling the hollow shell of the Iraqi government. Actions necessary for this role include, an ability to pummel (typically with air power and rapid reaction forces) any groups engaged in open warfare, and an ability to defend the borders. At all other times, US forces will be tightly sealed within their bases to prevent casualties. The problems with this strategy are manifold:

* Moral damage. US moral cohesion will collapse if casualties continue to mount. At minimum, the US political establishment will suffer a substantial loss in legitimacy (both parties) -- particularly since neither will square with the American people on the real reason we continue to stay in Iraq: OIL. Also, the perception of the US globally will continue to slide.

* Operational risk. Both open source movements (Sunni and Shiite) may focus their violence on the US. This situation puts the US against all of the factions with only the shell of the Iraqi government to back it up. This scenario gets worse if these forces (with Iranian support) can cut the supply lines to US forces.

* Expansion of the conflict. The entire strategy collapses if the war spreads to Iran or Saudi Arabia. By perpetuating the status quo, the US may be inadvertently contributing to the spread. Also, given the demonstration of Iraq, it's very likely that both Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf monarchies would rather fall than ask the US in to help.

John Robb's bookshelf contains all sorts of interesting tomes, including Philip Bobbitt's "Shield of Achilles". This weekend's Australian Financial Review has a long article on Philip Bobbitt called "Portrait of a grand American theoretician" which described him as a "Long war analyst and master of history" which drove me mildly nuts as it seems to inhabit a reality totally divorced from the one I perceive. Amongst all the descriptions of his grand southern plantation house, Washington clubs, illustrious relatives like Lyndon Johnson, his lineage back to English aristocracy, serving on the Nixon White House staff and the like is one central theme - that the "War on Terror" / "Long War" will last our lifetimes and that it is the result of a "Clash of civilisations" - and that fighting this "war" will require deliberate reductions of civil liberties in the West - all very scary stuff. And from my point of view, the scariest aspect is that it simply ignores what I see as the real cause - oil dependency - take away oil dependency and you have no cause for conflict - the battle between modernists and medievalists in the middle east can follow a parallel course in the middle east to the culture war in the US without any overlap (and with the religious fundamentalists hopefully losing, or at least retreating into their own tribal areas, in both regions).

I haven't read Bobbitt's book (though I vaguely recall skimming it in a book shop a couple of years ago) so I'm not sure if he's comparing the US to Achilles, but if he is I suspect its worth remembering the events chronicled in "The Iliad" - Achilles was a selfish and murderous brute who wasn't as invulnerable as he thought and whose passing wasn't exactly mourned by his comrades.

Moving on, Bloomberg has an article on Big Brother in the UK - "George Orwell Was Right: Spy Cameras See Britons' Every Move". While there's no doubt that the spread of surveillence cameras has reduced crime in the UK (and made offenders much easier to catch) its still hard to foresee a good long term outcome from the creation of an all-seeing security state.

It's Saturday night in Middlesbrough, England, and drunken university students are celebrating the start of the school year, known as Freshers' Week.

One picks up a traffic cone and runs down the street. Suddenly, a disembodied voice booms out from above:

``You in the black jacket! Yes, you! Put it back!'' The confused student obeys as his friends look bewildered.

``People are shocked when they hear the cameras talk, but when they see everyone else looking at them, they feel a twinge of conscience and comply,'' said Mike Clark, a spokesman for Middlesbrough Council who recounted the incident. The city has placed speakers in its cameras, allowing operators to chastise miscreants who drop coffee cups, ride bicycles too fast or fight outside bars.

Almost 70 years after George Orwell created the all-seeing dictator Big Brother in the novel ``1984,'' Britons are being watched as never before. About 4.2 million spy cameras film each citizen 300 times a day, and police have built the world's largest DNA database. Prime Minister Tony Blair said all Britons should carry biometric identification cards to help fight the war on terror.

``Nowhere else in the free world is this happening,'' said Helena Kennedy, a human rights lawyer who also is a member of the House of Lords, the upper house of Parliament. ``The American public would find such inroads into civil liberties wholly unacceptable.''

During the past decade, the government has spent 500 million pounds ($1 billion) on spy cameras and now has one for every 14 citizens, according to a September report prepared for Information Commissioner Richard Thomas by the Surveillance Studies Network, a panel of U.K. academics.

This sort of thing brings to mind Scott McNeally's old and accurate quote "privacy is dead, deal with it", which raised the thorny question of how we should adjust to an age where no one has any secrets.

“Privacy is dead, deal with it,” Sun MicroSystems CEO Scott McNealy is widely reported to have declared some time ago. Privacy in the digital age may not be as dead and buried as McNealy believes, but it’s certainly on life support.

OUR UNBRIDLED LOVE affair with all things technological has an evil twin: a seemingly unstoppable encroachment on our personal privacy. The same streaming video technology that allows grandma and grandpa to chat with their grandchildren is being used to spy on employees in the workplace or capture unsuspecting lovers stealing a kiss.

The rise of e-commerce also enables marketers of all stripes to capture bits and pieces of our buying and Web surfing habits. Database technology enables those bits and pieces of your daily life - the matrix of your personal world - to be assembled and repackaged thousand of ways and sold to anyone wanting to target you for a quick sale… or an unwitting scam. These are the darker angels of the digital age. “We know our privacy is under attack,” writes Simson Garfinkel in his excellent and severely under-appreciated book, “Database Nation.” “The problem is that we don’t know how to fight back.”

The truth is, fighting to protect privacy is a quixotic venture. Sure, there are any number of technologies, techniques and work-arounds you can employ, all in the effort to protect your privacy. But such a quest is like trying to dig a hole in middle of a fast flowing river. The rich and powerful gain some amount of privacy only because they can afford to grid their personal lives with a kind of digital body armor.

Garfinkel says we need to rethink privacy in the 21st Century. “It’s not about the man who wants to watch pornography in complete anonymity over the Internet. It’s about the woman who’s afraid to use the Internet to organize her community against a proposed toxic dump - afraid because the dump’s investors are sure to dig through her past if she becomes too much of a nuisance,” Garfinkel writes.

Poll after poll confirms that the American public relishes its privacy. The potential loss of privacy ranks as a major concern among an overwhelming majority of the citizenry. ...

The point here is that you and I need to push the envelope when it comes to protecting privacy if there is any hope of forestalling the swift erosion of our personal lives.

And we must also hold our government and those in authority over us accountable for protecting the information they are entitled to collect on us. It is a fight well worth the effort. But be forewarned: it can be an exhausting and frustrating task.

There are plenty of privacy organizations out there fighting on your behalf — you can easily find them online by searching for the words “privacy” and “advocacy.” (Or click on the links below.)

Amid the warp and woof of all these privacy horror stories — and flying well below the public’s radar - is the notion that there should be no privacy.

Author David Brin makes a compelling case against privacy in his unnerving book, “The Transparent Society.” Brin proffers that the more we attempt to protect privacy the more we are sure to lose it. Regardless of how many technologies and techniques the public can conjure to protect privacy, there will always be governments and the rich and powerful that are more able and more willing to subvert those same technologies for their own ends to the ultimate detriment of ours.

Brin’s radical notion then is that we all give up our privacy, equally. All records are open, all work place practices exposed to sunlight. The same goes for government and law enforcement operations. If the police have video surveillance cameras keeping track of the public then the public has a right to place the same video cameras in the police squad rooms. Among the crucial factors in Brin’s transparent world is accountability. Without equal accountability, the whole premise falls apart because, in the words of George Orwell’s “Animal Farm”: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

Accountability makes us all equal in a transparent society, Brin argues. “For instance, if some company wishes to collect data on consumers across America, let them do so,” Brin writes in his book, but “only on the condition that the top one hundred officers in the firm must post exactly the same information about themselves and all their family members on an accessible Web site.” Now, I don’t know about you but I’d be willing to trade my information for that kind of quid pro quo.

Of course I’m over-simplifying Brin’s arguments, which I’m not sure I totally buy into, but have to admit they are intriguing enough to make me twitchy about my personal privacy dogma. “Transparency is not about eliminating privacy,” Brin stresses. For example, Brin doesn’t suggest that our bedrooms become open access fodder for voyeuristic accountability freaks. Transparency “is about giving us the power to hold accountable those who would violate [our privacy]. Privacy implies serenity at home and the right to be let alone,” Brin writes.

Surely there are many hurdles to jump along the way to such a transparent society and Brin doesn’t deny or dodge discussing them. He simply gives a compelling alternative to what I ultimately believe will become a privacy rebellion if the various forces at work in the digital age are left unconstrained, free to rape and pillage our personal information.

David Brin himself tends to write about "The Transparent Society" from time to time in his blog, such as this recent post on the "WorldChanging book".

Across the 20th Century, a growing array of problems were solved through the application of professional skill. We came to rely increasingly upon professions ranging from medical doctors to law enforcement to teachers to farmers for countless tasks that an average family used to do largely for itself. No other trend so perfectly represents the last century as this one, spanning all boundaries of politics, ideology or geography.

And yet - just as clearly - this trend cannot continue much longer. If only for demographic reasons, the as the rate of professionalization and specialization must start to fall off, exactly as we are about to face a bewildering array of new -- and rapid-onrushing -- problems.

How will we cope?

Elsewhere I speak of the 21st Century as a looming "Age of Amateurs," wherein a highly educated citizenry will be able to adeptly bring to bear countless capabilities and individual pools of knowledge, some of which may not be up to professional standards, but that can find synergy together, perhaps augmenting society's skill set, at a time of need. We saw this very thing happen at the century's dawn, on 9/11. Every important, helpful and successful action that occurred on an awful day was taken by self-mobilized citizens and amateurs. At a moment when professionalism failed at every level. (Hear a podcast on this topic.)

It is important to note what a strong role technology played in fostering citizen action on 9/11. People equipped with video cameras documented the day and provided our best post-mortem footage. People with cell phones organized the evacuation of the twin towers. Similar phones stirred and empowered the heroes who fought back and made the Legend of Flight UA 93.

In sharp contrast, the events of Hurricane Katrina showed the dark side of this transition -- a professional protector caste (crossing party and jurisdiction lines: including republicans and democrats, state, local and federal officials) whose sole ambition appeared to be to staunch any citizen-organized activity, whatsoever. Moreover, the very same technology that empowered New Yorkers and Bostonians betrayed citizens in New Orleans. Thousands who had fully-charged and operational radios in their pockets were unable to use them for communication -- either with each other or the outside world -- thanks to collapse of the cellular phone networks.

This was a travesty. But the aftermath was worse! Because, amid all the finger-pointing and blame-casting that followed Katrina, almost no attention has been paid to improving the reliability and utility of our cell networks, to assist citizen action during times of emergency. To the best of my knowledge. no high level demand has gone out - from FEMA or any other agency - for industry to address problems revealed in the devastation of America's Gulf Coast. A correction that should be both simple/cheap and useful to implement.

What do we need? We must have new ways for citizens to self-organize, both in normal life and (especially) during crises, when normal channels may collapse, or else get taken over by the authorities for their own use. All this might require is a slight change -- or set of additions -- in the programming of the sophisticated little radio communications devices that we all carry in our pockets, nowadays.

How about a simple back-up mode for text messaging? One that could use packet-switching to bypass the cell towers when they are down, and pass messages from phone to phone -- or peer-to-peer -- at least among phones that are of the same type? (GSM, TDMA, CDMA etc.) All of the needed packet-switching algorithms already exist. Moreover, this would allow a drowning city (or other catastrophe zone) to fill with tens of thousands of little spots of light, supplying information to helpers and reassurance to loved ones, anywhere in the world.

Are the cell companies afraid their towers will be bypassed when there's no emergency? What foolishness. This mode could be suppressed when a good tower is in range and become useful automatically when one is not... a notion that also happens to help solve the infamous "last mile connectivity problem." Anyway, there are dozens of ways that p2p calls could be billed. Can we at least talk about it?

The same dismal intransigence foils progress on the internet, where millions of adults use "asynchronous" communications methods, like web sites, blogs and email, but shun "synchronous" zones like chat and avatar worlds, where the interface (filled with sexy cartoon figures) seem designed to ruin any chance of useful discourse. For example, by limiting self-expression to about a sentence at a time and ignoring several dozen ways that human beings actually organize and allocate scarce attention in real life.

When somebody actually pays attention to this "real digital divide" - between the lobotomized/childish synchronous chat/avatar/myspace world and the slow-but-cogent asynchronous web/blog/download world -- we may progress toward useful online communities like rapid "smart mobs." Only first, we are going to have to learn to look at how human beings allocate attention in real life! (For more on this: http://www.holocenechat.com)

Oh, there are dozens of other technologies that will add together, like pieces in a puzzle, synergizing to help empower the magnificent citizen of tomorrow. Facial recognition systems and automatic lookups will turn every pedestrian on any street into someone who you vaguely know... a prospect that cynical pundits will decry, but that was EXACTLY how our ancestors lived, nearly all of them, throughout human history. The thing to be afraid of is asymmetries of power, not universal knowledge. The thing to protect is not your secrecy, but your ability to deter others from doing you harm.

Likewise, I assure you that we are on the verge of getting both LIE DETECTORS and reliable PERSONALITY PROFILING. And yes, if these new machines frighten you, they should! Because they may wind up being clutched and monopolized by elites, and then used against us.

I am glad you're frightened. If that happens, we will surely see an era that makes Big Brother look tame.

And yet, the solution to this danger is not to "ban" such technologies! That is exactly what elites want us to do (so they can monopolize the methods in secret out of our skeptical eye). No, that reflex sees only half the story. Come on, open your mind a little farther.

What if those very same -- inevitable -- technologies wind up being used by all of sovereign citizens of an open democracy, say, fiercely applied to politicians and others who now smile and croon and insist that they deserve our trust? In other words, what if we could separate the men and women who have told little lies and admit it (and we forgive them) from those who tell the really dangerous and destructive whoppers? Those who are corrupt and/or blackmailed and/or lying through their teeth?

In that case, won't we have a better chance of making sure that Big Brother doesn't happen... ever?

Oh, it is a brave new world... We will have to be agile. Some things will be lost and others diminished. (We will have to re-define "privacy" much closer to home, or even just within it.)

On the other hand, if we don't panic, we may see the beginnings of the era of the sovereign and empowered citizen. An Age of Amateurs in which no talent is suppressed or wasted, and no problem escapes the attention of a myriad talented eyes.

The "Participatory Panopticon" that WorldChanging and Jamais Cascio frequently talk about is one example of transparency slowly and unreliably emerging, as the capability for ubiqitous recording of events emerges courtesy of our ever more capable personal communications devices.

English musician (and occasional venture capitalist) Peter Gabriel gave a talk at TED last year on one effort to make the abuse of power more transparent - the human rights watchdog "Witness".

Musician and activist Peter Gabriel explains the personal motivation behind his work with human-rights watchdog Witness. He shares stories of everyday people using video cameras to expose human rights abuses around the world, and poses the question: if injustice happens and a camera is there to capture it, can it be ignored? Peter Gabriel first took the musical stage by storm with the band Genesis, but has enjoyed a successful solo career with hits like "In Your Eyes." In 1989 he founded the Real World label for global music and the Real World Studios in Bath, England. In 1992 he co-founded Witness, a watchdog organization that gives video cameras to ordinary citizens to document human-rights abuses, so the perpetrators may be brought to justice.

Of course, information is always fluid and subject to manipulation from many directions, so David Brin's vision isn't immune to criticism - this piece at "Amor Mundi" being a (long) example.

As The Transparent Society is drawing to its close, David Brin retells the ancient Greek story of a “farmer, Akademos, who did a favor for the sun god.” Given the theme for which the tale will be meant to be illustrative here, it is interesting to note, as Brin does not, that the “favor” in question was the revelation to the divine twins Castor and Pollux of the secret location where their sister Helen had been hidden by Theseus. Akademos was something of a whistle-blower. In any case, in return for this favor, “the mortal was granted a garden wherein he could say anything he wished, even [engage in] criticism of the mighty Olympians, without retribution.” Brin goes on to muse, “I have often… wonder[ed] how Akademos could ever really trust Apollo’s promise. After all, the storied Greek deities were notoriously mercurial, petty, and vengeful…”

It isn’t exactly surprising to discover that Brin proposes as the resolution of his perplexity here that “there were only two ways Akademos could truly be protected,” and that these two exclusive possibilities will restage yet again the either/or that has structured the whole of his book.

“First,” he writes, “Apollo might set up impregnable walls around the glade…” Here, Apollo functions as the concentration of “centralized” authority, a divine Big Brother, Brin’s authoritarian “either,” as it were. But in this variation, this particular figuration of the one horn of the Brinian dilemma manages to evoke as well the Cypherpunk strategy of “strong privacy” against which he has also taken pains to distinguish himself over the course of the hundreds of pages that separate these concluding moves from his opening ones. And so, when he announces that “[a]las, the garden wouldn’t be very pleasant after that, and Akademos would have few visitors to talk to,” it is clear he means to denigrate the rather antisocial vision of the Cypherpunks and their fellow travelers quite as much as he would warn about the dangers of ubiquitous surveillance under authoritarian control (a concern he would share with market libertarians like the Cypherpunks and with most civil libertarians alike).

As for the Brinian “or” that yearns to nudge us over to an embrace of transparency, he writes: “The alternative was to empower Akademos, somehow to enforce the god’s promise. For this some equalizing factor was needed to make them keep their word…”

“That equalizing factor,” writes Brin, “could only be knowledge.”

But it is always right to ask after any blandly general claim to “knowledge,” not only knowledge of what? but knowledge for whom? knowledge to what purpose? And just so, it is difficult likewise not to wonder why knowledge of all things would be expected by anybody to be always an equalizer in fact, rather than, at least sometimes, an expression of and even the exacerbation of inequalities and the different desires they inspire. It is a truism to identify knowledge with power, and Foucault for one goes so far as to simply collapse the terms into the unlovely power/knowledge to drive the point home to those who would conveniently disremember it or disavow its entailments. Among these, wherever power is unequal it is hard to imagine what passes for knowledge will not likewise be, or the differential impact of its deployments by the powerful either.

Recall that Brin proposes in formulations early on in his book that those who shrink from the scrutiny of the powerful are engaged in more than a project rendered hopelessly quixotic by developmental urgencies he takes to be “inevitable” ones, but in a rather nefarious sort of project as well. Those who would curtail the scrutiny of the powerful in particular seem for Brin to hanker after the veiling or blunting or even blinding of some more generalized and congenial “seeing” to which we all might uniformly avail ourselves, at any rate in some ideal sense.

So too these later claims about a neutral and uniformly available “knowing” or “knowledge” of a world of natural fact underwrite as much as anything else Brin’s otherwise altogether counterintuitive confidence in a version of ubiquitous surveillance that would be immune to the worst political abuses and likely instead to be socially beneficial to all so long as it universally accessible. It is only because the facts of the world are apparently so stable or even manifest for Brin, so long as they are not distorted by the malice, errors, desires, or delusions of this or that misguided few, that he can imagine that a more collective recourse to the evidence gathered and distributed by ubiquitous surveillance could thereby police itself, would manage to stabilize without undue interference into an account that at once bespeaks righteousness and solicits consensus, would effloresce into yet another manifestation of the libertopian dream of spontaneous order.

“[M]ost honorable people,” after all, Brin assures us, “have little to fear if others know a great deal about them, so long as it goes both ways.” It is difficult to find such complacent reassurances anything but chilling to the bone. When has “honor” of all things ever secured for anybody a comfortable immunity from the depredations of the unscrupulous or the powerful? And who determines what will constitute an “honorable person” in the first place? Who determines just which conducts best bespeak the relative presence or absence of this exculpatory “honorableness” in some people more than others? Why would anybody expect the disbursal of even a knowledge that flows “both ways” between the relatively more and relatively less powerful to suffuse evenly and neutrally among the knowledgeable, and not to be prejudicially articulated by the self-interested ruses and strategies of the powerful themselves like everything else is?

The very metaphor of “transparency” itself for Brin amounts to the conjuration of a curiously clear-eyed, collective apprehension of the world implemented through ubiquitous surveillance technologies. Indeed, it is fair to wonder whether Brin’s evocation of “transparency” even counts finally as a formulation of surveillance at all. Surveillance is, after all, in Brin’s own terms, an “overlooking from above.” And it is unclear how a uniformly suffusing transparency could admit to the distributional unevenness of an up or a down and still remain, strictly speaking, a transparency.

In “Three Cheers for the Surveillance Society,” Brin mentions the work of Steve Mann (perhaps not exactly approvingly, calling him “radical and polemical”), a media performance artist and Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Toronto. When Brin goes on to offer up Mann’s work as an example of “reciprocal transparency” it is not clear to me whether or not he quite grasps the differences between his own vision of “transparency,” and Mann’s invocation of a "panopdecon" in which we speak truth to powers while at once testifying to our immersion and negotiations within them. In Brin’s cheerful interpretation, Steve Mann “prov[es] that we are sovereign and alert citizens down here, not helpless sheep. Mann contends that private individuals will be empowered… by new senses, dramatically augmented by wearable electronic devices.”

In fact, Mann counterposes to “surveillance” a host of interventions he describes instead as “sousveillance,” or scrutiny from below, conceived very much as matters of talking back to, offering critiques of, and coping with the complexities of emerging surveillance techniques. Sometimes satirical, sometimes defensive, sometimes documentary, sometimes amounting to direct political action, almost all of these sousveillant inverventions make use of ingenious original or reappropriated prosthetics, wearable computers, monitors, cameras, interfaces, displays. Like the activists of Project WITNESS and others who are struggling in this moment to provide cameras and other documentary technologies to especially vulnerable people, Mann’s sousveillance can scarcely be assimilated to a broader narrative in which “cameras” diffusely and indifferently accumulate to testify to manifest and hence, somehow, self-regulatory truths. Sousveillance, like surveillance, is neither the expression of a uniform and monolithically overbearing power nor an avenue toward the emancipatory circumvention of such a power, but a tactic of power in its particularity, deployed by variously constituted powers, immersed in the ongoing play of power.

For Brin, enhanced observation paired (via the very same surveillance and media tools) with universal accountability would body forth the facts themselves in a luminosity that burns away the public realm as any kind of space of ineradicable or interminable contestation quite as much as it would obliterate privacy in its glare. In this, Brin’s “transparency” is more than notionally correlated to the perfectly controlled discretionary opacity of the Cypherpunk’s “strong privacy” against which it would array itself. Both seek to implement a comparable ideal evacuation of the agonistic public through recourse to certain new tools on which their advocates have fixated their own attentions in a lingering fascination they have possibly mistaken for the tracking of developmental inevitabilities.

“I never promised a road map to a transparent utopia,” writes Brin a few pages later. “My main task was… to criticize… an appealing but wrongheaded mythology: that you can enduringly protect freedom, personal safety, and even privacy by preventing other people from knowing things.” But surely what worries many skeptics and critics of emerging regimes of ubiquitous surveillance is not so much that unspecified “other people” will “know things,” likewise unspecified, about them, as Brin would apparently have it. ...

Back in the distant past (over 20 years ago in fact), in the early days of the internet, I used to read the cypherpunks mailing list mentioned above. Bruce Schneier was something of a figure of reverence in cypherpunk circles courtesy of his book "Applied Cryptography", so I'll throw in Bruce's recent column on the "Automated Targeting System" here - an example of the myriad drawbacks of universal surveillence (I think its always worth considering the failure of the Stasi in East Germany when you try and build a massive dossier of information on everyone - its a huge cost, makes the citizenry paranoid and resentful and by and large achieves few useful results - you're better off spending your time and money trying to fix underlying problems).

If you've traveled abroad recently, you've been investigated. You've been assigned a score indicating what kind of terrorist threat you pose. That score is used by the government to determine the treatment you receive when you return to the U.S. and for other purposes as well.

Curious about your score? You can't see it. Interested in what information was used? You can't know that. Want to clear your name if you've been wrongly categorized? You can't challenge it. Want to know what kind of rules the computer is using to judge you? That's secret, too. So is when and how the score will be used.

U.S. customs agencies have been quietly operating this system for several years. Called Automated Targeting System, it assigns a "risk assessment" score to people entering or leaving the country, or engaging in import or export activity. This score, and the information used to derive it, can be shared with federal, state, local and even foreign governments. It can be used if you apply for a government job, grant, license, contract or other benefit. It can be shared with nongovernmental organizations and individuals in the course of an investigation. In some circumstances private contractors can get it, even those outside the country. And it will be saved for 40 years.

Little is known about this program. Its bare outlines were disclosed in the Federal Register in October. We do know that the score is partially based on details of your flight record--where you're from, how you bought your ticket, where you're sitting, any special meal requests--or on motor vehicle records, as well as on information from crime, watch-list and other databases.

Civil liberties groups have called the program Kafkaesque. But I have an even bigger problem with it. It's a waste of money.

The idea of feeding a limited set of characteristics into a computer, which then somehow divines a person's terrorist leanings, is farcical. Uncovering terrorist plots requires intelligence and investigation, not large-scale processing of everyone.

Additionally, any system like this will generate so many false alarms as to be completely unusable. In 2005 Customs & Border Protection processed 431 million people. Assuming an unrealistic model that identifies terrorists (and innocents) with 99.9% accuracy, that's still 431,000 false alarms annually.

The number of false alarms will be much higher than that. The no-fly list is filled with inaccuracies; we've all read about innocent people named David Nelson who can't fly without hours-long harassment. Airline data, too, are riddled with errors.

The odds of this program's being implemented securely, with adequate privacy protections, are not good. Last year I participated in a government working group to assess the security and privacy of a similar program developed by the Transportation Security Administration, called Secure Flight. After five years and $100 million spent, the program still can't achieve the simple task of matching airline passengers against terrorist watch lists.

In 2002 we learned about yet another program, called Total Information Awareness, for which the government would collect information on every American and assign him or her a terrorist risk score. Congress found the idea so abhorrent that it halted funding for the program. Two years ago, and again this year, Secure Flight was also banned by Congress until it could pass a series of tests for accuracy and privacy protection.

In fact, the Automated Targeting System is arguably illegal, as well (a point several congressmen made recently); all recent Department of Homeland Security appropriations bills specifically prohibit the department from using profiling systems against persons not on a watch list.

There is something un-American about a government program that uses secret criteria to collect dossiers on innocent people and shares that information with various agencies, all without any oversight. It's the sort of thing you'd expect from the former Soviet Union or East Germany or China. And it doesn't make us any safer from terrorism.

As I never tire of complaining, the cause of most of these "war on terror" side effects is our dependency on oil and the sooner we rid ourselves (as a planet) of our oil based transport system the sooner we can forget about the middle east and allow it to sort itself out. Billmon is fretting that instead of taking the sane option the prospect of "total war" still looms. He also has a medley of snippets from posts about the Iraq war over the years.

A "surge" of the size possible under current constraints on U.S. forces will not turn the tide in the guerrilla war . . . Moreover, major reinforcement would commit the US Army and Marine Corps to decisive combat in which there are no more strategic reserves to be sent to the front. It will be a matter of win or die in the attempt. In that situation, everyone in uniform on the ground will commit every ounce of their being to a hope of "victory," and few measures will be shrunk from.

Analogies come to mind: the Bulge, Stalingrad, the Battle of Algiers. It will be total war with all the likelihood of excesses and mass casualties that come with total war.

W. Patrick Lang and Ray McGovern

Surging To Defeat In Iraq

December 18, 2006We have to get out -- not because withdrawal will head off civil war in Iraq or keep the country from fallling under Iran's control (it won't) but because the only way we can stop those things from happening is by killing people on a massive scale, probably even more massive than the tragedy we supposedly would be trying to prevent.

Defeat, in other words, isn't the only alternative to failure. It could also lead to the kind of warfare that CIA counterinsurgency specialist Michael Scheuer warned about in his book Imperial Hubris:

"Progress will be measured by the pace of killing and, yes, by body counts. Not the fatuous body counts of Vietnam, but precise counts that will run to extremely large numbers. The piles of dead will include as many or more civilians as combatants because our enemies wear no uniforms . . ."

There was a time when I would have argued that the American people couldn't stomach that kind of butchery -- not for long anyway -- even if their political leaders were willing to inflict it. But now I'm not so sure. As a nation, we may be so desensitized to violence, and so inured to mechanized carnage on a grand scale, that we're psychologically capable of tolerating genocidal warfare against any one who can successfully be labeled a "terrorist." Or at least, a sizable enough fraction of the American public may be willing to tolerate it, or applaud it, to make the costs politically bearable.

Whiskey Bar

Heart of Darkness

September 24, 2005

All along, I've had the sneaking suspicion that the choices in Iraq would ultimately boil down to mass butchery or defeat. But, as the above post indicates, over the years I've become progressively less certain what the ultimate decision would be -- and whether and when the American military would flinch from the implications of that choice.

Next year may be the year we find out.