The Home Front

Posted by Big Gav

Four Corners tonight had a look at how we can cut our energy consumption and what is holding us back (transcipt).

While politicians clash noisily over global warming and how to fight it, millions of Australians are trying modestly to cut their energy use, to be a small part of a big solution.

But as Four Corners reveals, their efforts to save energy at home are being retarded by vested interests and a bewildering variety of rules and rebates, local, state and federal.

Households make 20 per cent of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions. Experts say household emissions could be cut by close to a third. Their prescription is a cocktail of moderate reforms that would change the way Australians build their homes, heat them, cool them and light them, and a tougher approach to power-guzzling products.

If there is a single instrument that could improve the energy efficiency of new houses, it is Australia’s building code, which sets minimum required standards for the building industry.

But how stringent are those standards? Compared with other countries, not stringent at all, Four Corners reveals. An innovative housing project in Queensland shows what could be achieved.

Typically, better design means more up-front cost – but that is offset by energy savings over time. "Not only are you reducing greenhouse gas emissions but you’ve got more money in your pocket," says energy policy consultant George Wilkenfeld.

If smarter home design can radically cut energy use, what can be done about the products inside? Four Corners asks if Australians have the facts when they buy appliances after building or renovating. If, for example, you’ve installed banks of funky "low-voltage" halogen lights, did you know you’re facing big power bills? Or that the giant plasma TV may be gulping more power than anything else in the house?

Large-screen TVs are among a number of new, energy-sapping products that are not yet required to have energy labelling or to meet any mandatory minimum standard. But even for appliances that wear them, can the energy star labels be trusted?

Four Corners commissioned laboratory tests on some cheap imported appliances which carry stars boasting energy efficiency and sell by the thousands each year. As reporter Jonathan Holmes reveals, the results are alarming - and call in question how well the rating system is policed.

Best article of the day is this (long) interview with Whole Foods CEO John Mackey about his vision of a new business paradigm. There's more at the link.

SUNNI: I have a lot of things I'd like to touch on with you, and I don't want to take too much of your time, so let's jump right in. In doing some research, I found you being referred to as an "ex-leftist libertarian". I thought that a very odd phrase, since many individuals come to the freedom philosophy from a left perspective -- and lots of pro-freedom people are more concerned with personal and social issues than economic ones; that's generally considered to be a "leftist" slant. What do you think of that phrase? Does it fit you?

JOHN: I think that depends upon how "leftist" is defined. Usually people who define themselves as "leftists" are opposed to capitalism, economic freedom, and believe that the coercive power of government should be used to create more equality and social justice in society. Usually people on the left have sympathy for democratic socialism. When I was in my very early 20's I believed that democratic socialism was a more "just" economic system than democratic capitalism was. However, soon after I opened my first small natural food store back in 1978 with my girlfriend when I was 25, my political opinions began to shift. Operating a business was a real education for me. There were bills to pay and a payroll to be met and we had trouble doing either because we lost half of our initial $45,000 of capital in our first year. Our customers thought our prices were too high and our employees thought they were being underpaid, and we were losing money. Renee and I were only being paid about $200 a month and the business was a real struggle. Nobody was very happy and Renee and I were now seen as capitalistic exploiters by friends on the left who believed we were overcharging our customers and exploiting our workers -- all because we were apparently selfish and greedy.

I didn't think the charge of capitalist exploiters fit Renee and myself very well. In a nutshell the economic system of democratic socialism was no longer intellectually satisfying to me and I began to look around for more robust theories which would better explain business, economics, and society. Somehow or another I stumbled on to the works of Mises, Hayek, and Friedman, and had a complete revolution in my world view. The more I read, studied, and thought about economics and capitalism, the more I came to realize that capitalism had been misunderstood and unfairly attacked by the left. In fact, democratic capitalism remains by far the best way to organize society to create prosperity, growth, freedom, self-actualization, and even equality.

I no longer think of myself as a leftist, but I definitely don't think of myself as from the right either. For the past 25 years I've thought of myself as a libertarian, but I'm now beginning to move away from that label as well. I have a number of intellectual problems with libertarianism as a political philosophy as it currently exists. I believe we need a new social/political/economical/environmental movement in the world today and I've got some definite ideas what this movement should look like.

SUNNI: You sure seem to be popular in the libertarian community, despite having arrived here through a side door, so to speak. How do you account for that? [laughs]

JOHN: I'm not aware that I'm popular in the libertarian community. On the contrary, I've frequently found myself criticized for lacking sufficient doctrinal purity by many in this movement.

SUNNI: Perhaps it's the celebrity element at work, then, John ... In doing background research for this interview, I came across mentions of you at several libertarian sites -- Advocates for Self-Government and several blogs. I don't recall seeing any critical comments. But I'm sure that you'd get them after a speech -- the movement doesn't suffer a lack of critics. [laughs]

JOHN: It could be the celebrity element. I'm not shy about telling the media or anyone else that I'm a libertarian. I suppose I've brought some favorable publicity to the libertarian movement. I hope so anyway.

SUNNI: I'm sure you have. One of the Conspirators who blogs with me is a huge fan of Whole Foods Market -- she's a stakeholder in more than one meaning of the term -- and I know a number of loyal Whole Foods Market customers in the pro-freedom community. I know that some wouldn't bat an eye at its Declaration of Interdependence, for example, but others might be surprised to see how often the word "collective" and its variants show up on the Whole Foods Market web site ... or to see ideas like "shared fate" and "community citizenship" in its core values statement. How do you square all that with being libertarian?

JOHN: I personally don't see any contradictions here. Human beings are highly social animals and we evolved over hundreds of thousands of years living in small hunting and gathering tribes. I believe that much of our fulfillment as human beings comes from our participation in the various social organizations that we belong to. Today we are raised in families, live in neighborhoods and communities, and are members of a number of greater collectives. For example, I am a member of the following collectives: Austin, Texas, The United States, Homo sapiens, vertebrates, DNA-based life forms, planet Earth, Milky Way Galaxy, etc. I'm also a voluntary member of a number of organizations including my marriage with Deborah Morin, Whole Foods Market, various long-distance backpacking groups, various animal welfare/animal rights groups, and various libertarian organizations, plus many others. Even my physical body is a collective consisting of many billions of cells working together in various organs to stay alive and pass on its genetic material into the future.

I think the reason why many libertarians object to the words "collective", "shared fate", and "community citizenship" is that they associate those words with coercive, involuntary organizations such as the forced collectivization of Soviet agriculture under communism or other totalitarian political organizations. Needless to say I don't use these words in these contexts. I believe in voluntary cooperation as the key principle for organizing any collective organization. Whole Foods Market is a collective based on voluntary cooperation between all the various stakeholders. No one is forced to cooperate against their will and all are free to withdraw from the collective organization anytime they wish to. A collective without freedom is by nature coercive and is therefore unlikely to lead to human flourishing. However, collectives based on freedom and voluntary cooperation can lead to very high levels of human flourishing. Indeed, I seriously doubt that high levels of human flourishing are even possible without voluntary cooperation from millions of various communities and collectives.

SUNNI: It sounds to me like you aren't a libertarian of a Randian persuasion -- wholly profit-driven and focused on the self; is that accurate?

JOHN: That is correct. I was very inspired by Ayn Rand's novels like millions of other people have been. However, I don't agree with some of her philosophies. For example: I don't think selfishness is a virtue and I don't believe that business primarily exists to make a profit. Profit is of course essential to any business to fulfill its mission and to be successful and to flourish and I will defend the goodness and appropriateness of profits for business with great passion. However, profit is not the primary purpose of business. Renee and I didn't begin Whole Foods Market to maximize profits for our shareholders. We began it for three main reasons: we thought it would be fun to create a business; we needed to earn a living; and we wanted to contribute to the well-being of other people.

As the business grew we created our mission statement back in 1985 and have tried to fulfill it ever since. That mission very clearly articulates that we have collective -- there's that word again -- responsibilities to all the various constituencies who are voluntarily cooperating with the company. In order of priority these constituencies or stakeholders are: customers; team members; investors; vendors; community; and environment.

We measure our success on how well we meet the needs and desires of all of these various stakeholders. All must flourish or we aren't succeeding as a business. I'll email you a graphic that represents how Whole Foods views the voluntary cooperation between the various stakeholders:

We call this a "New Business Paradigm" because it puts the Business Mission and Core Values at the center of the business model -- not maximizing profits. Profits aren't the primary goal of the business. They are an important result of fulfilling the Business Mission and meeting the needs and desires of customers. I'm writing a book on Whole Foods philosophy of business right now so it's hard for me to do justice to all the ideas and answer all the standard objections in this interview. My more complete statement on this will need to wait for the publication of the book. I'll share two ideas as food for thought here though.

Free-market economists have done a major disservice to capitalism and to business by making profit maximization the supposed primary goal of business. The terrible reputation of business in the world today is a direct result of the belief that business has no other purpose besides maximizing profits. The average person believes that business should care about its customers, employees, society, suppliers, the environment -- as well as its investors. The fact that business philosophers and economists articulate a philosophy that business should only care about maximizing profits and shareholder value (and has no other compelling ethical responsibilities to any of the other stakeholders) has done incalculable harm to the reputation of business. The "brand of business" in the widest sense is pretty terrible throughout the world. Read David Korten's book When Corporations Rule the World to get a good perspective on how many intellectuals see corporations and big business today -- a threat to the well-being of the entire world. The anti-globalization movement is actually an anti-corporation movement and it is a direct result, in my opinion, of the faulty logic of the shareholder value maximization model. You and I know that business and capitalism are helping increase prosperity throughout the world. Too bad the economists have done such a poor job of intellectually justifying the intrinsic ethical nature of business and the capitalist system. Both business and capitalism have terrible reputations as a result. Socialism, communism, and anti-globalization are all reactions to this philosophy. I sometimes wonder whether any of these horrible philosophies would have had much of a following except for the intellectual failures of our economists to properly understand the real purpose of business.

Second, there is a fundamental paradox that I call the "paradox of shareholder value". The best way to maximize shareholder value is to not make maximizing shareholder value the primary purpose of the business. Why not? Because it is the business that satisfies customers best that has the most customers, the highest sales, and the most profits. The best way to satisfy customers best is to organize the entire business around satisfying the customer. Every communication the business makes towards its customers, its employees, and the media should be about putting the customer first. Ultimately the best way to satisfy customers' needs best is to actually put those needs first. If profit is the articulated primary goal of the business then it is unlikely that the employees or management of the business will dedicate themselves to customer satisfaction to the same degree they would if customer happiness was seen as more important than investor profits. In the first case customer happiness is merely a means to an end -- maximizing profits. In the customer-centered business, however, customer happiness is an end in itself and because it is it will be pursued with greater interest, passion, attention and empathy than the profit centered business is capable of.

Let me give you an analogy that may make this point better: What is the key to happy marriage? Is my wife's happiness an end in itself for me or is her happiness merely a means to a different end -- my own personal happiness? It has been my experience that I am happiest in my marriage when my love for my wife causes me to place her needs and desires first -- ahead of my own. When my wife is happy then I am happy. When she isn't happy, then I'm not happy. I achieve my personal happiness in marriage best by not focusing directly on it, but by focusing on her happiness as the primary goal for me in the marriage. That is the way love works, in my opinion. The beloved's happiness is an end in itself -- not a means to some other end. Paradoxically by seeking to maximize my wife's happiness, I also maximize my own. However, that is a secondary by-product of my desire for her personal happiness. Fortunately for me my wife shares my philosophy of marriage and reciprocates my dedication to her happiness with an equal dedication to my own happiness as well.

Similarly to a happy marriage, the most successful businesses put the customer first -- ahead of the shareholders. They really have to have this dedication to the customer to maximize customer happiness. Customers aren't stupid. They know when they are being misled or merely being used. It is also difficult to impossible to truly inspire the creators of customer happiness, the employees, with the ethic of profit maximization. Maximizing profits may excite shareholders, but I assure you most employees don't get very excited about it even if they accept the validity of the goal. It is my business experience that employees can get very excited and inspired by a business that has an important business purpose (such as selling the highest quality natural and organic foods) and teaches them to put the needs of the customers first. People enjoy serving others and helping them to be happy -- when they know this is their primary goal and are also rewarded for successfully doing so.

The customer-centered business is usually the most successful and the most profitable, while the shareholder centered business usually underperforms over the long-term. I suggest reading Jim Collins' two books Built to Last and Good to Great for empirical evidence to this viewpoint. The ultimate test of these two business theories, however, is in the marketplace -- not in theoretical arguments. My company, Whole Foods Market, is a mission-driven business that puts the customer first, the team members second, and the shareholders third. We are winning competitive battle after competitive battle in the marketplace against businesses which adhere to the philosophy of maximizing profits and shareholder value as their primary goal. Whole Foods has never had a store we open ever fail in the marketplace. We have never lost a competitive battle in 27 years of business! Why not? Because the profit-centered businesses we compete against cannot beat us in the marketplace. Our customer and team member-centered business model beats them every single time.

You may or may not agree with my business philosophy, but it doesn't really matter. The ideas that I'm articulating result in a more robust business model than the shareholder-maximization model that it competes against. They will triumph over time, not by persuading intellectuals and economists through argument, but by winning the competitive test of the marketplace. Someday businesses such as Whole Foods which adhere to a stakeholder model of customer and employee happiness first will dominate the entire economic landscape simply because it is a more robust business model. The old shareholder model that most economists believe in will not successfully compete over the long-term with the new paradigm that Whole Foods represents and that I've tried to articulate here. The better business model will win in the marketplace and it's the Whole Foods model. Wait and see!

SUNNI: [laughing] Geez, John, you're getting ahead of me -- answering questions I haven't asked yet! So, what does it suggest to you about this country that two very different types of retailer -- Whole Foods Market and Wal-Mart -- are both so profitable?

JOHN: It means that the mass market is segmenting in food -- just like it is doing in every other category as well. Some people want the cheapest food and some people want the highest quality food with high levels of customer service. Wal-Mart meets the first group of people and Whole Foods meets the needs of the second group.

SUNNI: You've mentioned your management style, and I would like to explore that more. It's certainly worked very well, but it doesn't seem to be a very libertarian one. Do you see your management style as paradoxical given your libertarian philosophy?

JOHN: Most corporations in the United States are hardly the epitome of libertarian utopias. In fact, most corporations in the United States are organized as top-down, command & control, hierarchical systems. Very little personal freedom exists in these corporations. Their employees are often managed through either pure financial incentives -- greed -- or through fear -- "my way or the highway". Whole Foods is very, very different. Our mission at Whole Foods can be summed up by our slogan "Whole Foods, Whole People, Whole Planet". We put great emphasis at Whole Foods on the "Whole People" part of this mission. We believe in helping support our team members to grow as individuals -- to become "Whole People". We consciously use Maslow's hierarchy of needs model to help our team members to move up Maslow's hierarchy. As much as we are able, we attempt to manage through love instead of fear or greed. We allow tremendous individual initiative at Whole Foods and that's why our company is so innovative and creative. Most retail companies create a prototype retail store format and then cookie-cutter reproduce it across the country. Think McDonalds. Not Whole Foods. We have no prototype store. All our stores are unique. Why? Because our team members are constantly innovating, experimenting, and improving them. Whole Foods is very much committed to a Hayekian discovery process and our team members -- both as individuals and as members of teams -- are leading this Hayekian discovery process. As our team members learn and grow as individuals, as they become self-actualized, as they become "Whole People", our company better fulfills its mission to all of its stakeholders.

The seeming paradox that you keep hinting at is no paradox at all. Human beings are both individuals and members of communities (or collectives). We learn and grow best through relationships and our growth will always be limited without them. I haven't met anyone that I consider to be self-actualizing who did it all by themselves. Freedom as an ideal is a very, very incomplete ideal when it lacks love. Freedom is my highest "political ideal", but love is my highest "personal ideal". We need both. There is no paradox and there is no contradiction here. Freedom and love: let us marry these two together!

SUNNI: [laughing] Now that sounds like a marriage made in heaven, John! And thanks for not taking my pushing here too personally; I actually don't see it as a paradox either, but I imagine that you know of people in the pro-freedom community -- I sure do -- who seem to have an almost phobic reaction to anything that moves beyond the individual level. I'm an individualist, but I'm no idiot -- we're social animals, and one of the things that interests me most about libertarians -- especially as a psychologist -- is how they approach those two aspects of human nature.

JOHN: Some libertarians may be using their political ideology as a psychological defense to avoid the challenge of further personal growth. From a psychological standpoint the challenge for all of us is to simultaneously continue to individuate as individuals while also integrating closer to our communities. In my experience, libertarians are more enthusiastic about the individuation part than the integration part. However, psychologically healthy, self-actualizing people need to be doing both.

SUNNI: A very interesting observation, John ... and of course, if the individuals aren't psychologically healthy, it's very difficult to create a vibrant, pro-freedom community. This reminds me: I've seen people call you an anarchist, but in other places I've read others who claim you think some government is necessary, which would make you at the very least a minarchist. Which is it?

JOHN: I'm not an anarchist. Of course government is necessary. Without a monopoly of force by some institution -- let's call it "government" -- we will have various violent gangs and private armies struggling for political control and the winner will become the de facto government. While government is necessary the never-ending political challenge is to find ways to keep government in check. "Who guards the guardians?" remains a huge philosophical issue. The United States has done better than most other countries in this regard with the creation of the Constitution and Bill of Rights, and the various governmental checks and balances. Unfortunately, as we both know, government has been steadily gaining in power ever since the United States came into being. What is the solution? There is no simple solution--just the ongoing and continual quest by people who care about freedom and individual rights to work to expand them and lessen governmental power. Progress can be made. For example, there is much more freedom in Eastern Europe than there was 30 years ago.

SUNNI: Yes, there's been a lot of progress, but I think many would say that's in spite of the kind of government you're speaking of. I don't want to focus on this too much, but I'm curious about how you might think a monopoly of force by any institution can be genuinely limited, short term as well as long term. It seems to me to be the nature of powerful institutions to always work to retain, and gain, more power.

JOHN: Competition is the best way to limit any power -- economic, social, political, or military. For example, it is good that our states have to compete for businesses and citizens. To some extent this puts a limit on their ability to tax their citizens because many will vote with their feet and move to a different state. California has been driving business to move to other States for a couple of decades now. Our federal government could obviously use more competition as well. As financial capital becomes more and more liquid and mobile it will be increasingly easy to move it to more favorable tax homes and more free locales. That may be illegal, but it will increasingly happen anyway if our federal government becomes too oppressive. Breaking the federal government's monopoly on money is obviously very important. I think we are pretty near to doing that right now with increasing competition to the dollar from the euro and eventually the yuan. People and businesses will be able to denominate their investments and assets in whatever currency they have the most faith in.

So competition with other nations will become increasingly important as a check on our federal government's power. Obviously Constitutional amendments could be very powerful checks as well, but are difficult to get into law. Probably the most important thing we can do, however, is continue to fight the good fight for more liberty. Citizen activism can make a huge difference in the world and frequently has.

Liberty has always fought an uphill battle throughout history. You can pretty much name any period of time in history that you wish to, and if you study it carefully, you'll see that liberty was always very constrained. There never was a golden age for liberty. I would argue, in fact, that right now there probably exists more absolute personal and political freedom across the entire globe than at any time in history. Even here in the United States. We tend to forget how little freedom that women and minority citizens have had in America throughout our history. There has been tremendous progress made in these 2 areas within my own lifetime. We tend to forget the progress we have collectively made and instead focus more on what has been lost or not yet gained. Progress tends to advance in more of a spiral fashion than a straight line upward. ...

A few years ago my cranky inner-libertarian would have been a bit aghast at some of these ideas, but the neo-conservative era has stripped me of any tolerance for dogmatism and my current employer has acclimatised me to the psycho-babble about non-hierarchical, team oriented corporations. One of the stranger perks of my current job (with what looks from the outside like just another mammoth corporate entity) is "leadership coaching" from a corporate psychologist, who is a little bit startled by the extreme dedication to moulding corporate culture shown by the company (I'm not even an employee, just a mercenary contractor).

I don't think he's used to dealing with individuals like me (normally they only deal with highly stressed senior execs, whereas I'm more of a direction setter with no line management duties whatsoever in my current role), especially ones who diligently keep to an 8 hour work day and show no signs of stress at all - apparently most clients they deal with have extreme anxiety about the pace of change, the pressure to keep on top of the job and worries about the future, while I don't suffer from any of these maladies (or the problems they cause on the home front) - and told him I love change - especially changing jobs. He had to shut me up at one stage as I launched into a compare and contrast of the interview techniques used by the cream of London's corporate citizens and which ones I thought were the best for rapidly identifying talent. Anyway, these guys seem to act as the equivalent of priests to the executive class, hearing confession and offering guidance on the correct way to behave - hopefully a few of them are getting into "new paradigm" guidance now...

Dan at The Daily Reckoning had some words today about the risk posed by the debt levels bought on by our new millenium credit bubble. Also at the DR, Bill Bonner on the latest New Era of capitalism.

--The world is not flat. Instead, it increasingly resembles a piece of cheap elastic. The elastic is stretching beyond what we thought was previously possible. Sooner or later we expect it to snap, leaving a giant red welt on someone's backside. But until then, what exactly is unfolding and what does it mean for investors?

--At the upper end of the elastic band are the money shufflers. These days, the money shufflers are best represented by Stephen Schwartzman and his merry band of pirateers at Blackstone (NYSE:BX). The good ship Blackstone was up 13% on Friday in its first day of trading.

--Hey, if you can make money buying and selling assets with other people's money, why not? We've got nothing against the pirates personally. But when the chief preoccupation of the market is making deals and not building businesses, well then, we've reached a very late, decadent stage of the credit cycle.

--At the other end of the elastic band is the stretched middle class of the Western world. On the one hand, it doesn't look so bad. Low consumer price inflation has kept the supply of electronics and manufactured goods down. It's not exactly bread and circuses. But with a decent credit line, you can have a lot of fun at Bunnings.

--However, the reality is at odds with the appearance of growing wealth. "Real wages fall as profits rise," writes David Uren in the Australian. Two factors have kept real wages low for Australian workers. First, the globalization of the work force keeps a lid on wage growth. This is simple supply and demand. As the supply of labour has grown with the inclusion of China and India into the global economy, the price of labour, generally has gone down.

--And then there is the distribution of profits. Workers are getting less of them directly while corporations are taking a larger share. In the U.S., corporate profits as a share of national income are up from 7.8% in 2002 to 10.5% today. The same general trend can be found in France, Germany, Japan, and Australia.

--In fairness, corporate spending in the form of business investment has also kept the unemployment level at all-time lows. Business spending is the key to a healthy business cycle. So the fact that corporate profits are up as a percentage of national income isn't automatically a sign that big, bad, corporate fat cats are doing well...while the working stiff is getting stiffed.

--But despite the cheap electronic goods at Harvey Norman, the working stiff has got to start wondering if this whole globalisation thing is going to work out for him. "The average household is now supporting debts that are 58.7 per cent greater than their total annual income, whereas at the last election, debts were 41.3 per cent more than a year's income." This from a Reserve Bank of Australia study released this week. But that data doesn't really tell the whole story.

--In 1977, the household debt to disposable income ration was 35.1%. Obviously, that meant for every dollar of income a household had, it had only thirty five cents in debt. Today, every dollar in income is burdened by $1.58 in debt. This is progress?

--But wait! That debt also shows up on the household balance sheet as an asset. That's because the biggest component of household debt is the mortgage. "Debt levels are rising, but we are choosing to use the debt more productively to buy assets that traditionally rise in value, like shares and property," says CommSec economist Martin Arnold.

--Fair enough. But here's the question...if Australians are forced to go deeper in debt for longer and spend more of their disposable income on an asset they never fully own, just what kind of an asset is a house anyway? Aren't you better off renting? Renting doesn't have the same tax advantages, of course. But it doesn't have the same debt disadvantages.

--What about capital gains? That is the holy grail of property investment. But here's the thing. Assets fluctuate in value. Debts do not. Right now, Australians are comfortable loading up on debt as long as the assets they buy with that debt go up faster than the cost of servicing the debt. But that's the flimsy and false logic behind all credit bubbles...that you can borrow cheap, bid up an asset, and flip it to some other schmuck before interest rates rise, money supply shrinks, and assets fall value again.

--The assets will fall in value again, both absolutely and adjusted for inflation. And then what is your average Australian left with? A whole lot of debt, an asset falling in value, and flat rage growth in a cut- throat global economy. Argh. Sounds like walking the plank to us.

--Will super save everyone? ... Our long-term forecast? Inflation will erode the value of super returns the way it erodes the value of cash year after year. When you throw in a massive liquidity-contraction correction in markets, well then it looks even gloomier for the Aussie investor/worker/shareholder.

--Taking on debt is not a way to get rich. It's only a kind of financial newspeak that makes it seem like taking on debt is okay. "War is Peace. Ignorance is Strength. Freedom is Slavery," Orwell wrote.

"Debt is Wealth," he would have added if he were writing today.

Stewart Brand at The Long Now Foundation has a look at "humanity's immune system" in "Paul Hawken, The New Great Transformation" (mp3).

The title of Paul Hawken’s talk, “The New Great Transformation,” has two referents, he explained. Economist Karl Polanyi’s 1944 book, THE GREAT TRANSFORMATION, said that the “market society” and modern nation state emerged together in Europe after 1700 and divided society in ways that have yet to be healed.

Karen Armstrong’s 2006 book, THE GREAT TRANSFORMATION, explores “the Axial Age” between 800 and 200 BC when the world’s great religions and philosophies first took shape. They were all initially social movements, she says, acting on revulsion against the violence and injustice of their times.

Both books describe conditions in which “the future is stolen and sold to the present,” said Hawken— a situation we are having to deal with yet again.

His new book, BLESSED UNREST, was inspired by the countless business cards that earnest environmentalists would hand him after his lectures all over the world. After a while he had 7,000, and he wondered, “How many environmental groups are there in the world?” He began actively building a now-public database, WiserEarth.org, which includes social justice and indigenous rights organizations because he found they indivisibly overlap in their values and activities.

The database now has 105,000 such organizations. The still-emerging taxonomy of their “areas of focus” has 414 categories, amounting to a “curriculum of the 21st century”— Acid Rain, Living Wages, Tropical Moist Forests, Peacemaking, Democratic Reform, Sustainable Cities, Environmental Toxicology, Watershed Management, Human Trafficking, Mountaintop Removal, Pesticides, Climate Change, Refugees, Women’s Safety, Eco-villages, Fair Trade… Extrapolating from carefully inventoried regions to those yet to be tallied, he estimates there are over 1,000,000 such organizations in the world, adding up to the largest and fastest growing Movement in history.

The phenomenon has been overlooked because it lacks the customary hallmarks of a movement— no charismatic leaders, no grand theory or ideology, no “ism,” no defining events. The new activist groups are about dispersing power rather than aggregating power. Their focus is on ideas rather than ideology— ideologies are clung to, but ideas can be tried and tossed or improved. The point is to solve problems, usually from the bottom up. The movement can never be divided because it is already atomized.

What’s going on? Hawken wondered if humanity might have some collective intelligence that we don’t yet understand. The metaphor he finds most useful is the immune system, which is the most complex system in our body— more complex than the entire Internet— massive, distributed, subtle, ingenious, and effective. The opposite of a hierarchical army, its power is in the density of its network. It deals with problems not through frontal attack but complex negotiation and rapprochement.

Much of the new movement, Hawken said, was inspired, at root, by the slavery abolitionists and by the Transcendentalists Emerson and his student Thoreau. Emerson declared that “everything is connected,” and Thoreau wound up going to jail (and making it cool) by taking that idea seriously in social-justice terms.

Now, as in the Axial Age, activism comes from acting on the realization that “all life is sacred.”

The Edge magazine has a new edition out - as always I'm a sucker for anything mentioning heretics:

By "dangerous ideas" I don't have in mind harmful technologies, like those behind weapons of mass destruction, or evil ideologies, like those of racist, fascist, or other fanatical cults. I have in mind statements of fact or policy that are defended with evidence and argument by serious scientists and thinkers but which are felt to challenge the collective decency of an age. The ideas in the first paragraph, and the moral panic that each one of them has incited during the past quarter century, are examples. Writers who have raised ideas like these have been vilified, censored, fired, threatened, and in some cases physically assaulted.

Every era has its dangerous ideas. For millennia, the monotheistic religions have persecuted countless heresies, together with nuisances from science such as geocentrism, biblical archeology, and the theory of evolution. We can be thankful that the punishments have changed from torture and mutilation to the canceling of grants and the writing of vituperative reviews. But intellectual intimidation, whether by sword or by pen, inevitably shapes the ideas that are taken seriously in a given era, and the rear-view mirror of history presents us with a warning. Time and again people have invested factual claims with ethical implications that today look ludicrous. The fear that the structure of our solar system has grave moral consequences is a venerable example, and the foisting of "Intelligent Design" on biology students is a contemporary one. These travesties should lead us to ask whether the contemporary intellectual mainstream might be entertaining similar moral delusions. Are we liable to be enraged by our own infidels and heretics whom history may some day vindicate?

I suggested to John Brockman that he devote his annual Edge question to dangerous ideas because I believe that they are likely to confront us at an increasing rate and that we are ill equipped to deal with them. When done right, science (together with other truth-seeking institutions, such as history and journalism) characterizes the world as it is, without regard to whose feelings get hurt. Science in particular has always been a source of heresy, and today the galloping advances in touchy areas like genetics, evolution, and the environment sciences are bound to throw unsettling possibilities at us. Moreover, the rise of globalization and the Internet are allowing heretics to find one another and work around the barriers of traditional media and academic journals. I also suspect that a change in generational sensibilities will hasten the process. The term "political correctness" captures the 1960s conception of moral rectitude that we baby boomers brought with us as we took over academia, journalism, and government. In my experience, today's students — black and white, male and female — are bewildered by the idea, common among their parents, that certain scientific opinions are immoral or certain questions too hot to handle.

What makes an idea "dangerous"? One factor is an imaginable train of events in which acceptance of the idea could lead to an outcome that only recently has been recognized as harmful. In religious societies, the fear is that that if people ever stopped believing in the literal truth of the Bible they would also stop believing in the authority of its moral commandments. That is, if today people dismiss the part about God creating the earth in six days, tomorrow they'll dismiss the part about "Thou shalt not kill." In progressive circles, the fear is that if people ever were to acknowledge any differences between races, sexes, or individuals, they would feel justified in discrimination or oppression. Other dangerous ideas set off fears that people will neglect or abuse their children, become indifferent to the environment, devalue human life, accept violence, and prematurely resign themselves to social problems that could be solved with sufficient commitment and optimism.

All these outcomes, needless to say, would be deplorable. But none of them actually follows from the supposedly dangerous idea. Even if it turns out, for instance, that groups of people are different in their averages, the overlap is certainly so great that it would be irrational and unfair to discriminate against individuals on that basis. Likewise, even if it turns out that parents don't have the power to shape their children's personalities, it would be wrong on grounds of simple human decency to abuse or neglect one's children. And if currently popular ideas about how to improve the environment are shown to be ineffective, it only highlights the need to know what would be effective. ...

Glenn Greenwald has a look at "Iran - The Next War ?" and the cartoonish level of public politics practiced in the US.

Throughout 2006, it was unclear whether the president's increasingly antagonistic rhetoric towards Iran was merely a political ploy to satiate his warmongering political base or whether, notwithstanding our incapacitating occupation of Iraq, the president himself really believed that war with Iran might be inevitable.

But the 2006 midterm elections did not put an end to the president's militarism towards the Iranians. Quite the contrary, once the elections were over -- and even with a clear anti-war message delivered by voters -- the president began not only sending signals that he would escalate America's military commitment to the war in Iraq but also intensify our hostile posture towards the Iranians.

Prohibited Debates

Just as all of the cartoonish demonization of the evil Saddam precluded a meaningful national debate about the consequences of invading Iraq, so, too, is the president's embrace of the same caricature of the Iranians precluding meaningful debate about our policy towards Iran. Complex questions that the U.S. must resolve regarding our overall Middle East policy are urgent and pressing. Yet, in a virtual repeat of the debate-stifling war march into Iraq, arguments which treat these matters as nothing more complex than League of Justice cartoons -- in which the Good heroes must and will defeat the Evil villains -- dominates discourse, ensuring that no meaningful debate occurs.

The fundamental problem is that as a nation we do not actually debate the real issues because they are too politically radioactive, and because the simplistic appeals to Victory over Evil obscure, by design, the genuine limits on American power and the drain these conflicts are placing on finite American resources. The real issue is whether the U.S. wants to maintain its presence and controlling influence in the Middle East and, if so, (a) why does the U.S. want to do that?, and (b) what Americans are willing to sacrifice to preserve that dominance.

But Americans during the Bush presidency have had no significant, constructive discussion of whether the U.S. has any real interests in continuing to exert dominance in the Middle East, primarily because doing so requires a debate about the role of oil and our commitment to Israel, both of which are strictly off limits, as the president himself told us in a January, 2006 speech:The American people know the difference between responsible and irresponsible debate when they see it. They know the difference between honest critics who question the way the war is being prosecuted and partisan critics who claim that we acted in Iraq because of oil, or because of Israel, or because we misled the American people. And they know the difference between a loyal opposition that points out what is wrong, and defeatists who refuse to see that anything is right.

It may be the case that the U.S. should seek to preserve its influence in the Middle East. Perhaps we want to control oil resources or assume primary responsibility for ensuring a steady and orderly world oil market. Or perhaps we want to commit ourselves to defending Israel as the only real outpost of Middle Eastern democracy and/or an ally of one degree or another in protecting our vital strategic interests, if any, in that region.

There are coherent (if not persuasive) arguments, pro and con, for all of those positions, but these issues have been embargoed by social and political orthodoxy, and no examination of them is allowed (if one wants to continue to be heard in the mainstream). So we dance around the real questions and are stuck with superficial and contrived "debates" about what we are actually doing -- about all the new Hitlers and the "Evil" we must confront and our need to be Churchill instead of Chamberlain -- all of which obscures our choices, our limits and basic reality.

If preserving our dominance of the Middle East is a goal we want to prioritize, then we would need to decide what sacrifices we are willing to bear in order to reach it. We must determine whether and how we will massively expand our military, the increase in indiscriminate force we are willing to accept, and how we are going to pay for our imperial missions. Because as long as we are committed to dominating that region, we are going to be engaged in a long and likely endless series of brutal wars against religious fanatics and various nationalists who simply do not want us there and are willing to fight to the death -- making all sorts of sacrifices themselves -- to prevent us from dominating their countries.

TreeHugger has a post on Ed Burtynsky's movie "Manufactured Landscapes".

After hearing Edward Burtynsky speak and watching his slides at the Worldchanging booklaunch, we raced to the movie theatre to see Manufactured Landscapes: "a feature length documentary on the world and work of renowned artist Edward Burtynsky....he film follows Burtynsky to China as he travels the country photographing the evidence and effects of that country’s massive industrial revolution. Sites such as the Three Gorges Dam, which is bigger by 50% than any other dam in the world and displaced over a million people, factory floors over a kilometre long, and the breathtaking scale of Shanghai’s urban renewal are subjects for his lens and our motion picture camera."

At Worldchanging Ed talked about the dolly shot at the beginning of the movie, where the camera rolls down a side aisle past endless rows of workers clad in identical yellow jackets making who knows what, we think irons but it does not seem possible that the world could possibly need so many. It goes on. And on. And that is even before the credits.

It is really impossible to describe. Coal yards the size of small states.

The Three gorges dam, twice as big as any other in the world, swallowing up cities where people are paid by the brick to dismantle their own homes.

Burtynsky swears he is not being political; the movie website says "What makes the photographs so powerful is his refusal in them to be didactic. We are all implicated here, they tell us: there are no easy answers. The film continues this approach of presenting complexity, without trying to reach simplistic judgements or reductive resolutions." But the viewer can't help but make them, the imagery is too strong. It is an intensely political movie and you come out shocked to the core. You wonder what the point is in doing anything to mitigate climate change when you see those piles of coal, those endless seas of high-rises with an air conditioner in every window.

I'm so thoroughly mind-boggled by tonight's news footage of soldiers shipping out to occupy Aboriginal communities here that I'm a little lost for words. I thought the Rodent's "national emergency", declared to deal with social and health problems in remote areas after 12 years of inaction, was simply yet another ploy to try and distract voters from global warming, Iraq, petrol prices, slumping government approval ratings in the polls and the like - now I'm pretty much stumped - what are we turning into ? Crikey rounds up a few comments from the blogs:

Back to the future. Howard and Brough appear to have overleaped the Pearson bandwagon and jumped straight to 1950s Australia. - Stoush

It's Hustler's fault. Who knew that ending child abuse was as simple as banning porn and booze for indigenous populations? -- Reason, Hit & Run

Isn't it an election year? Advertised as a response to an inquiry into child s-x abuse in Aboriginal communities, the alcohol ban in NT indigenous communities probably has far more to do with politics than anything else. -- The Bad Rash

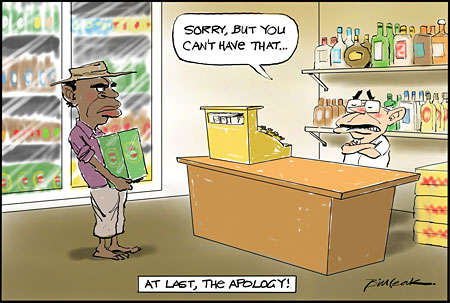

The S word. If this is a national emergency, then why hasn’t John Howard done anything in 12 years about the decades of underfunding and cycle of abuse much of which has been exacerbated by white Australian Governments, the stolen generation actions of whom, Howard refuses to say sorry for. -- Tumeke

Because you can, you should. Howard’s Something Approach: 1.) Something Must Be Done. 2.) This is Something We Could Do. 3.) Let’s Do That Thing Then. -- Hoyden about town

Links:

The Age - Water Tank Rules To Be Softened

Brisbane Times - Analysts say uranium may soar to $US200

Fortune - Wyoming's natural gas boom sees growing pains

Andrew Cameron (Sydney Anglicans) - The peak oil society. Made a convert Dave ?

Global Public Media - Dr. Albert Bartlett, In Depth. Note - population isn't currently a problem - I've yet to see anything that convinces me that we are in overshoot yet - and if the models are correct I suspect we can handle the 9 billion people we expect to max out at just fine after we adjust the energy system and the industrial production system.

The Independent - The fight for the world's food. Of course, the utter idiocy of turning food into fuel is not helping matters.

CNN - San Francisco City Government Bans Bottled Water

CBC News - Protect your saving and beware of energy 'vampires,' experts warn

New Scientist - Ionic liquid offers greener recycling of plastics

Wired - June 22, 1969: ummm, the Cuyahoga River is on fire ... again

The Observer - Lay off America - its heart is in the right place.

Tribbie - The ‘Most Severely Wounded’ American Soldier

Village Voice - Dick Of Arabia

SMH - Australian PM Fuels Talk Of Iraq Withdrawal

Boing Boing - Cory Doctorow Podcasts Bruce Sterling's "The Hacker Crackdown