Feeling Shut In ?

Posted by Big Gav in peak oil

The LA Times has an interesting article on the impact high oil prices are having on small towns in the US - "Gas prices box in an Alabama community".

Norman Finklea filled his jug just past a gallon, letting the analog meter come to rest at $3.88. Then he walked into Roy's with his four crumpled bills and a litany of anxieties, which were rising with the price of gas.

He didn't need to tell them to Saulsberry. As the proprietor of this little country store in one of the poorest counties in Alabama, Saulsberry has already heard them all. It doesn't matter what kind of cars pull up to pumps these days -- stretchy old hooptie sedans, scuffed econo-boxes, king-cab pickups -- anxiety is their common cargo. With the high price of gas, Saulsberry said, "people just can't go as much."

Finklea, a freelance construction worker, had paid a friend $5 to pick him up at his house a few miles down the road and drive him here. His own car was back at home with its pin on empty, he said. He needed it to drive to work in the morning. Finklea said high gas prices were the reason he paid only half his light bill last month, the reason he and his wife were trying to get by with less food, the reason he is turning down jobs that are more than 30 miles away.

Those jobs, he said, are not worth driving to anymore.

CIBC's Jeff Rubin is predicting $200 a barrel oil by 2012 (like Caltex Australia's Des King).

Crude oil prices will soar to more than $200 (U.S.) per barrel over the next five years – driving Canadian pump prices to $2.25 a litre and forcing a fundamental transformation in the North American economy, says Jeff Rubin, chief economist with CIBC World Markets Inc. In a new report, Mr. Rubin forecast a continued run-up in crude prices, despite a slowing world economy and slumping petroleum demand in United States, the world's leading oil consumer.

He said he expects crude prices – now trading at above $116 (U.S.) a barrel - to average $150 by 2010, and more than $200 by 2012. That would translate into pump prices of $7 (U.S.) per gallon in the United States, and $2.25 per litre in Canada, double the current levels.

“Whether we are already at the peak of world oil production remains to be seen, but it increasingly clear that the outlook for oil supply signals a period of unprecedented scarcity,” the economist said.

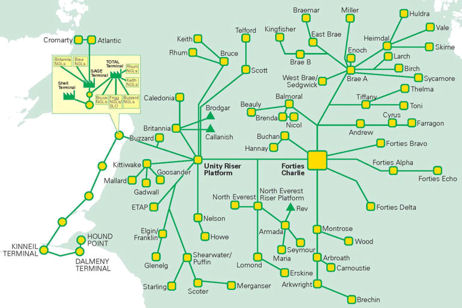

The Guardian has a report on the strike at the Grangemouth refinery in Scotland, which has resulted in the shutdown of around 700,000 bpd of oil production from the North Sea.

Drivers were today urged not to panic buy fuel after talks to avert a strike at one of Scotland’s largest oil refineries failed. A two-day walkout by up to 1,200 workers at the Grangemouth refinery is set to begin on Sunday after negotiations between the Unite union and refinery management broke down yesterday.

Ineos, the company that runs the plant, warned of “chaos and disruption” if the strike went ahead. Petrol prices have already risen amid anticipation of fuel shortages. However, the Scottish government today said it had contingency plans in place to ensure supplies were maintained throughout the dispute.

John Swinney, the finance minister, said there were enough supplies of petrol and diesel to last well into May if buying levels remained normal. “The government has been working very clearly over the last few days to ensure we are prepared for this,” he told BBC Radio Scotland.

Unite officials have spent the last two days in talks with Ineos management in an attempt to resolve the dispute, which was sparked by changes to the company’s pension scheme. “Unite’s negotiators were disappointed with the company’s refusal to withdraw controversial pensions plans, and the two-day strike will therefore go ahead,” a union spokesman said. Ineos accused Unite of being “hell bent” on going through with the strike, saying managers had put forward “significant” new proposals during the talks.

Motoring organisations have urged drivers to remain calm. “I think motorists in Scotland are going to be wondering what on earth is going to happen, but there still is no reason for people to panic,” Paul Watters, the head of public affairs at the AA, said. “We have to put our trust in the petroleum industry to keep Scotland’s pumps filled. What motorists don’t need to do is to keep their tanks full. They should keep filling the normal amount.”

Sky News reports the refinery has now closed, and asks "Can Scotland Cope ?.

TOD Europe has some running commentary and reports on the Grangemouth story.

Bloomberg reports that oil consumption in emerging markets now exceeds that of the US (though there is still a very long way to go in terms of per capita usage - which is the important factor to keep in mind as per capita incomes equalise).

Traffic jams in Beijing and humming air conditioners in Dubai are replacing U.S. highways and suburbs as the driver of global oil prices.

China, India, Russia and the Middle East for the first time will consume more crude oil than the U.S., burning 20.67 million barrels a day this year, an increase of 4.4 percent, according to the International Energy Agency in Paris. U.S. demand will contract 2 percent to 20.38 million barrels daily, the IEA says.

Economic growth of more than 8 percent in China and India, coupled with increasing car ownership among the countries' combined populations of 2.45 billion people, will more than compensate for falling U.S. demand. Oil use worldwide will increase 2 percent this year because of growth in emerging markets, the Paris-based IEA says.

``Does the U.S. matter anymore?'' said Mike Wittner, head of oil research at Societe Generale SA in London. ``Has the U.S. mattered for the last few years? It is debatable. As far as the oil market is concerned, demand growth is going to be continued to be driven by China and the Middle East.''

The Wall Street Journal's Environmental Capital blog has a look at Saudi oil production - "Peak Oil? Saudis Squeeze the Stone Even Harder".

As oil reserves get harder and more expensive to suck out of the ground, one big question looms: Is Saudi Arabia facing “practical peak oil” or the real thing?

Saudi Arabian officials made waves last week with an announcement that the kingdom would voluntarily limit future oil production, in order to leave oil wealth “for future generations.” Last weekend, Saudi officials said that the world’s biggest oil producer won’t be diving into new exploration projects after next year, citing sluggish Western demand and the search for alternative fuels to petroleum.

So are the Saudis smartly shepherding their oil resources? Or are they obliquely acknowledging that getting them out of the ground will be increasingly difficult and expensive?

Neil King in the WSJ reports today (sub reqd.) on the challenges facing Saudi Aramco as it launches its last big project before taking an upstream hiatus: The tricky development of the big Khurais field, which could pump more than 1 million barrels of oil per day. The paper says:Even in Saudi Arabia, home to more than a quarter of the world’s known recoverable reserves, the age of cheap and easily pumped oil is over. To tap Khurais, Saudi Arabian Oil Co., known as Aramco, has embarked on the most complex earth- and water-moving project in its history. It is spending up to $15 billion on a vast network of pipes, oil-treatment facilities, deep horizontal wells and water-injection systems that it calls “one of the largest industrial projects being executed in the world today.”

With crude oil approaching $120 despite sluggish demand growth in the U.S., the idea of “peak oil”—that the world’s oil glass is already half-empty—is increasingly gaining currency. Other once-formidable oil producers like Russia, the U.K., and Mexico are all seeing production decline as fields age. While Aramco has been very good at squeezing the maximum amount of oil out of each reservoir, even the world’s biggest oil producer is finding that it’s no longer shooting fish in a barrel.

Business Week has a column from "automotive expert" Ed Wallace, claiming "There Is No Gas Shortage" - "but Washington, Wall Street, and ethanol and oil and gas companies want you to think there is" (the dateline for this was April 1, so perhaps it wasn't serious).

Gasoline reserves on hand are at the highest levels since the early 1990s, which is remarkable considering the nation's refineries have been cutting back on the production of gasoline because their margins have declined. In fact, average gasoline reserves on hand have risen since this past October, while oil reserves in this country have gone up virtually every week this year—and only fog in the Houston Ship Channel that kept oil tankers from unloading their crude one week kept it from being every week.

In the same Bloomberg article that quotes from Bodman's CNBC appearance on Mar. 4, he also said that it was thanks to ethanol that the gasoline problem isn't even worse. He then added that the fact that making ethanol is forcing up prices of other farm commodities, including hog and chicken feed, is "nowhere near as important as trying to relieve pressure on [gasoline] supplies."

Of course, there is no pressure on gasoline supplies in this country as of today, but Bodman's statement must have made eyes roll among the executives at Pilgrim's Pride PPC; the Pittsburg, (Tex.) poultry producer announced 1,100 layoffs on Mar. 13, closing one processing plant and 6 of their 13 distribution centers because their company's outlay for chicken feed went up $600 million last fiscal year and was on track to increase by another $700 million this year.

Here's the scorecard, in case you missed it. There's no shortage of gasoline or oil in the U.S. today, and we have near-record reserves on hand. Meanwhile the Congressional mandate for ethanol has jacked up the price of chicken feed for Pilgrim's Pride, which is the U.S.'s largest processor of chickens and turkeys—by $1.3 billion. And that's for just one company processing chicken. This is what passes for acceptable to our Energy Secretary?

Just so we can all get on the same page, here are the verifiable facts on oil supplies, production, and gasoline demand.

In January of this year, the U.S. used 4% less petroleum than we did a year ago. (Oil demand was down 3.2% in February.) Furthermore, demand has been falling slowly since July of last year. Ronald Bailey of Reason Online has pointed out that worldwide production of oil has risen 2.5% in the first quarter, while worldwide demand has grown by only 2%.

Production is expected to increase by 3.3% in the second quarter, and by as much as 4.1% by the third quarter. The net result is that the U.S. daily buffer for oil production against demand, which was a paltry 1.5 million barrels as recently as 2005, is now up to 3 million barrels in excess capacity today. ...

As for the speculators, in 2000 approximately $9 billion was invested in oil futures, while today that number has gone up to $250 billion. Now, if any publicly traded company had an additional $241 billion put into its stock in the same period, its stock would rise out of sight too—even if the company was not worth anywhere near that amount of market capitalization.

Moving on to the weak U.S. dollar as a primary cause for skyrocketing oil prices—there is "some" truth in that statement. But consider this: The dollar has depreciated 30% against the world's currencies since 2002, while the price of oil has gone up 500%. So is it the weak dollar that has caused a 500% increase in the price of oil, or is it the extra $241 billion worth of speculation? You can make the call on that one.

Possibly just to ensure oil prices don't respond to real-world market conditions, Goldman Sachs (GS) forecast on Mar. 7 that turbulence in the oil market could cause oil to spike as high as $200 a barrel. This flies in the face of all known information—but then again, Goldman Sachs is the world's biggest trader of energy derivatives, and its Goldman Sachs Commodities Index is a widely watched barometer of energy and commodities prices.

Jeff Vail has a few Thoughts on Demand Destruction, which should be updated at TOD this week.

Oil is currently well over $100/barrel. Demand is effectively holding steady in the US despite this recent run-up in price. There are some measures that suggest a decrease in demand, and the press has seized upon these to “prove” that high oil prices are causing people to drive less. I think this is cherry-picking of statistics: one commonly watched demand indicator, the one-week domestic gasoline demand figure as published by the Energy Information Agency in This Week in Petroleum actually shows a 91,000 barrel per day increase in gasoline demand for the week ending April 11, 2008 over the week ending April 13, 2007 (9.338 mbpd in ’08 vs. 9.247 mbpd in ’07). That’s a 0.98% increase year on year—so where’s the demand destruction??

This flies flat in the face of repeated statements recently in the press and blogosphere that gasoline demand is going down, so let’s look at it a bit more carefully. Here are the EIA’s full historical tables for gasoline demand, both week ending and 4-week average. Using the smoother 4-week average, the 2008 demand has been consistently lower than in 2007, but not by much. However, using the finer-resolution one week data, 2008 demand was higher than 2007 for the weeks ending 4/11/08, 3/28/08, but lower the weeks ending 4/4/08 and 3/21/08. For two of the last four weeks, demand for gasoline has been higher in 2008 than in 2007. This is hardly conclusive evidence of demand destruction, and completely ignores that the most recent demand figure shows a year-on-year increase.

Will we see significant demand destruction in the future? There is no clear answer to that at this time, but I think one thing is clear: it’s time to take a deeper look at the mechanics behind how demand destruction will work, if and when we see it (or, if we already are).

Does a lack of demand destruction when oil is well over $100/barrel mean that prices must go even higher to destroy demand? How much higher? Or is it enough that prices hold at this level for long enough to cause people to gradually make long-term purchases with this price in mind, and thereby destroy demand? How long? Finally, how much of current US demand destruction (to whatever degree it exists—even if only as a decrease in growth of demand) is due to current economic conditions, and how much can be attributed to price alone? ...

It's also worth pointing out that this analysis only considers US gasoline demand. Even if there is an ongoing demand destruction of 1% per year in the US, two significant factors overwhelm this: global demand growth remains strong, and net exports are falling precipitously (by 150,000 barrels per day in March alone). More on these items in future posts...