The Methane Trigger For Geoengineering

Posted by Big Gav in geoengineering

Jamaias Cascio has yet another column on geoengineering up at Open The Future, this one looking at the methane being released from the melting Siberian permafrost, with Jamais arguing events like this make some form of geoengineering mandatory.

I remain highly dubious about the vast majority of proposed geoengineering approaches, though the bioengineering approaches Jamais talks about are preferable to further experimentation upon the atmosphere or oceans (though large scale terra preta creation - or even "green concrete" seem like the best bet with the least risk of horrible side effects) - Methane Trigger for Geo & Bio Engineering.

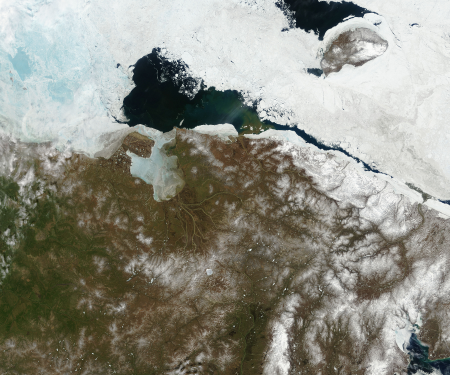

Methane (CH4) is 20-25 times more powerful a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide (CO2). We're quite familiar with one source of atmospheric methane -- enteric fermentation in cattle (see my innumerable posts about cheeseburger carbon footprints). But there's another source of methane that has the potential to be far greater in volume, and correspondingly far more threatening to the climate. It's the methane from bogs and marshlands that is trapped under the Siberian permafrost.

Well, that was trapped. As the permafrost melts, the methane is now starting to leak out.Methane, a potent greenhouse gas, is leaking from the permafrost under the Siberian seabed, a researcher on an international expedition in the region told Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter on Saturday.

"The permafrost now has small holes. We have found elevated levels of methane above the water surface and even more in the water just below. It is obvious that the source is the seabed," Oerjan Gustafsson, the Swedish leader of the International Siberian Shelf Study, told the newspaper.

The tests were carried out in the Laptev and east Siberian seas and used much more precise measuring equipment than previous studies, he said.

And that's pretty much all that's been said, so far. It does seem to confirm Russian reports from a couple of years ago. But it's unfortunate that the reporters covering this didn't mention just how much methane is trapped under the permafrost in Siberia, because the amount is staggering.

The most conservative estimates I've seen start at around 70 billion metric tons of methane -- the equivalent in greenhouse terms to 1.6 trillion metric tons of CO2. As a point of comparison, the total annual greenhouse footprint in the US is about 7 billion tons; globally, the annual footprint is about 30 billion tons.

If this methane leak continues to increase, we may be facing a disastrous result that no amount of renewable energy, vegetarianism, and bicycling will help. This is one scenario in which the deployment of geoengineering is over-determined, probably needing to remain in place for quite a while as we try to remove the methane (or, at worst, wait for it to cycle out naturally over the course of a decade or so). It's also a scenario that might require large-scale use of bioengineering. As I wrote a few years ago, when the Russian reports started to come out:Chemical processes in the atmosphere break down CH4 (in combination with oxygen) into CO2+H2O -- carbon dioxide and water. In addition, certain bacteria -- known as methanotrophs -- actually consume methane, with the same chemical results. [...] It appears to me that what will be the most effective means of mitigating and remediating the gargantuan methane excursion from the Siberian permafrost melt would be using genetically-modified forms of methanotrophic bacteria, with greater oxidation capacity and the Archaea-derived resistance to extreme cold (these may well go hand-in-hand, as one way that deep sea methanotrophs survive the icy depths is through internal energy production from methane consumption). Given the size of the region, we'll need lots of them, but that's another advantage of biology over straight chemistry: the methanotrophs would be reproducing themselves.

Is it a perfect solution? No -- it's unproven, with unknown implications, and (at the very least) would result in some levels of CO2 emissions (although with a far smaller greenhouse footprint than the original methane). But the leak of permafrost methane is one of those lesser-known stories that could end up determining whether we make it through this century or not. It's one of the reasons why I think that geoengineering is a near-certainty.

Jamaias also has some thoughts about events that shaped the human evolutionary process - Thinking About Thinking.

Seventy-four thousand years ago, humanity nearly went extinct. A super-volcano at what's now Sumatra's Lake Toba erupted with a strength more than a thousand times greater than that of Mount St. Helens in 1981. Over 800 cubic kilometers of ash filled the skies of the northern hemisphere, lowering global temperatures and pushing a climate already on the verge of an ice age over the edge. Genetic evidence shows that at this time – many anthropologists say as a result – the population of Homo sapiens dropped to as low as a few thousand families.

It seems to have been a recurring pattern: Severe changes to the global environment put enormous stresses on our ancestors. From about 2.3 million years ago, up until about 10,000 years ago, the Earth went through a convulsion of glacial events, some (like the post-Toba period) coming on in as little as a few decades.

How did we survive? By getting smarter. Neurophysiologist William Calvin argues persuasively that modern human cognition – including sophisticated language and the capacity to plan ahead – evolved due to the demands of this succession of rapid environmental changes. Neither as strong, nor as swift, nor as stealthy as our competitors, the hominid advantage was versatility. We know that the complexity of our tools increased dramatically over the course of this period. But in such harsh conditions, tools weren't enough – survival required cooperation, and that meant improved communication and planning. According to Calvin, over this relentless series of whiplash climate changes, simple language developed syntax and formal structure, and a rough capacity to target a moving animal with a thrown rock evolved into brain structures sensitized to looking ahead at possible risks around the corner.

Our present century may not be quite as perilous as an ice age in the aftermath of a super-volcano, but it is abundantly clear that the next few decades will pose enormous challenges to human civilization. It's not simply climate disruption, although that's certainly a massive threat. The end of the fossil fuel era, global food web fragility, population density and pandemic disease, as well as the emergence of radically transformative bio- and nanotechnologies – all of these offer ample opportunity for broad social and economic disruption, even devastation. And as good as the human brain has become at planning ahead, we're still biased by evolution to look for near-term, simple threats. Subtle, long-term risks, particularly those involving complex, global processes, remain devilishly hard to manage.

But here's an optimistic scenario for you: if the next several decades are as bad as some of us fear they could be, we can respond, and survive, the way our species has done time and again: By getting smarter. Only this time, we don't have to rely solely on natural evolutionary processes to boost intelligence. We can do it ourselves. Indeed, the process is already underway.